The Art of Douglas Fairbanks (1925) 🇬🇧

Someone is smiling. “What,” he asks, “The art of Douglas Fairbanks?” Yes, my dear sir, the art of Douglas Fairbanks. I have not forgotten the days of his cowboy comedianhood, nor his cheery, American face, which no make-up can change or disguise; I have not forgotten the fact that he never did a really subtle bit of acting in his life. Yet I stick to it — Fairbanks is an artist, one of the kinema’s dozen, and out of that dozen perhaps the most powerful of all in the beauty he can command and give to the world.

by E. R. Thompson

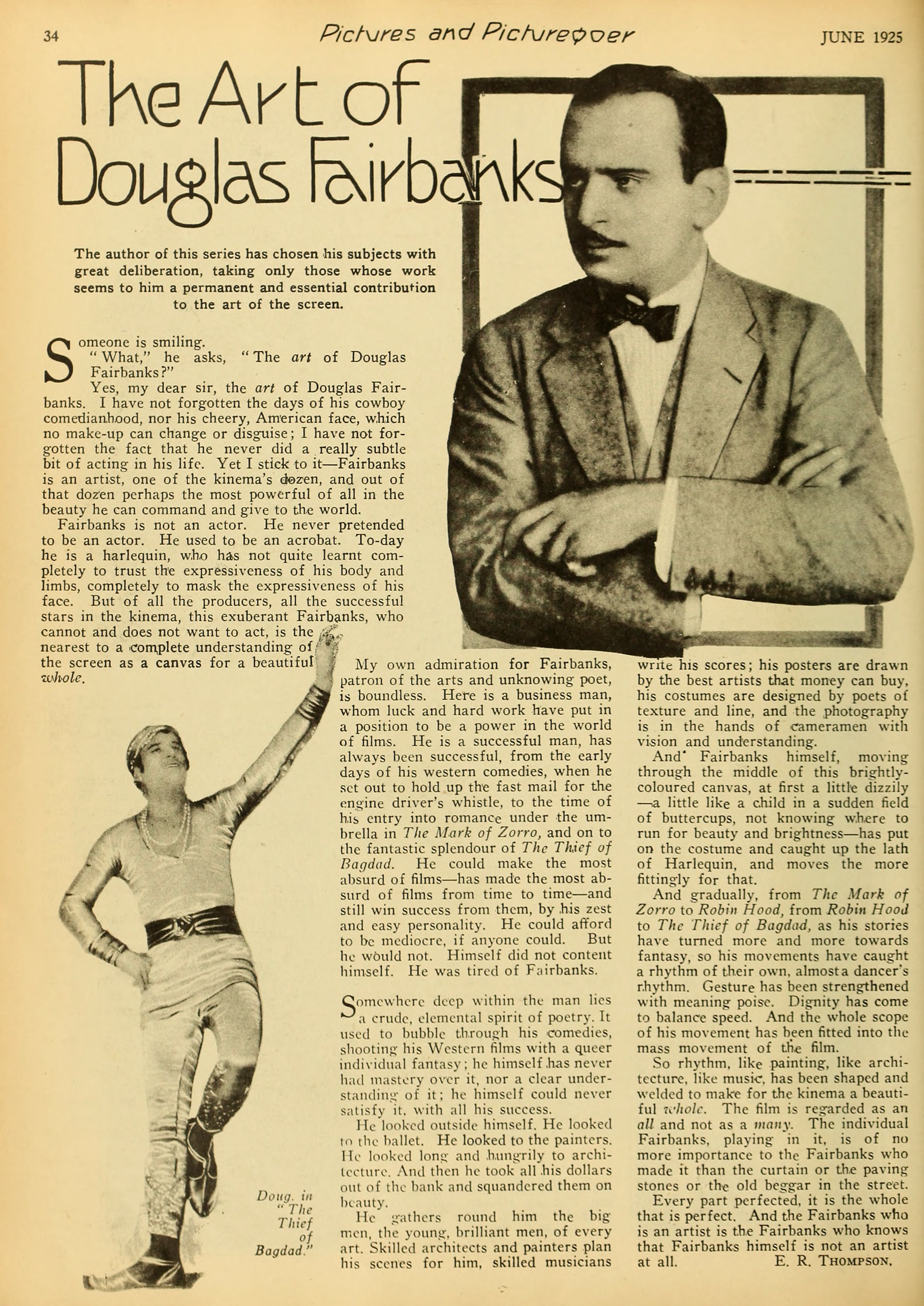

Fairbanks [Douglas Fairbanks Sr.] is not an actor. He never pretended to be an actor. He used to be an acrobat. To-day he is a harlequin, who has not quite learnt completely to trust the expressiveness of his body and limbs, completely to mask the expressiveness of his face. But of all the producers, all the successful stars in the kinema, this exuberant Fairbanks, who cannot and does not want to act, is the nearest to a complete understanding of the screen as a canvas for a beautiful whole.

My own admiration for Fairbanks, patron of the arts and unknowing poet, is boundless. Here is a business man, whom luck and hard work have put in a position to be a power in the world of films. He is a successful man, has always been successful, from the early days of his western comedies, when he set out to hold up the fast mail for the engine driver’s whistle, to the time of his entry into romance under the umbrella in The Mark of Zorro, and on to the fantastic splendour of The Thief of Bagdad. He could make the most absurd of films — has made the most absurd of films from time to time — and still win success from them, by his zest and easy personality. He could afford to be mediocre, if anyone could. But he would not. Himself did not content himself. He was tired of Fairbanks.

Somewhere deep within the man lies a crude, elemental spirit of poetry. It used to bubble through his comedies, shooting his Western films with a queer individual fantasy; he himself has never had mastery over it, nor a clear understanding of it; he himself could never satisfy it with all his success.

He looked outside himself. He looked to the ballet. He looked to the painters. He looked long and hungrily to architecture. And then he took all his dollars out of the hank and squandered them on beauty.

He gathers round him the big men, the young, brilliant men, of every art. Skilled architects and painters plan his scenes for him, skilled musicians write his scores; his posters are drawn by the best artists that money can buy, his costumes are designed by poets of texture and line, and the photography is in the hands of cameramen with vision and understanding.

And Fairbanks himself, moving through the middle of this brightly-coloured canvas, at first a little dizzily — a little like a child in a sudden field of buttercups, not knowing where to run for beauty and brightness — has put on the costume and caught up the lath of Harlequin, and moves the more fittingly for that.

And gradually, from The Mark of Zorro to Robin Hood, from Robin Hood to The Thief of Bagdad, as his stories have turned more and more towards fantasy, so his movements have caught a rhythm of their own, almost a dancer’s rhythm. Gesture has been strengthened with meaning poise. Dignity has come to balance speed. And the whole scope of his movement has been fitted into the mass movement of the film.

So rhythm, like painting, like architecture, like music, has been shaped and welded to make for the kinema a beautiful whole. The film is regarded as an all and not as a many. The individual Fairbanks, playing in it, is of no more importance to the Fairbanks who made it than the curtain or the paving stones or the old beggar in the street.

Every part perfected, it is the whole that is perfect. And the Fairbanks who is an artist is the Fairbanks who knows that Fairbanks himself is not an artist at all.

—

Doug in The Thief of Bagdad.

Collection: Picturegoer Magazine, June 1925

—

The Art of… series:

- 1925–01 — Alla Nazimova

- 1925–02 — Adolphe Menjou

- 1925–03 — John Barrymore

- 1925–04 — Charles Chaplin

- 1925–05 — Pola Negri

- 1925–06 — Douglas Fairbanks Sr.

- 1925–07 — Leatrice Joy

- 1925–08 — Bernhard Goetzke

- 1925–09 — Mary Pickford

- 1925–10 — Ernst Lubitsch

- 1925–12 — Ian Keith