The Art of Bernhard Goetzke (1925) 🇬🇧

“And who is Bernhard Goetzke?” I can hear a dozen voices asking the question, and can guess at a dozen minds framing it in thought. For that is the penalty of the film actor who happens to work and to be born outside of the United States — his name means nothing — it is just a name, no more. No publicity man has shouted it through trumpets of brass.

by E. R. Thompson

No electrics have flared it across the sky. It may be the name of genius, but it carries no spell. We listen when it comes our way at last, and nod, and ask politely whose it may be.

The name of Bernhard Goetzke is that of a dramatic giant, one of the finest actors upon the screens of the world, but it is less familiar to the bulk of picturegoers than the flowing syllables of Bull Montana’s name, less familiar than that of Baby Peggy Montgomery, even than that of Rin-Tin-Tin.

So much for genius — and publicity! The connoisseur of acting, however, knows Goetzke well, has marked him down from his first appearance on an English screen, and closely followed his work through all of the half-dozen pictures which have brought across the Channel in the last three years this curious and powerful personality.

Our first sight of Goetzke was as the detective De Witt in “Dr Mabuse the Gambler.” A little later we came across him again as a mysterious Yogi in “Above All Law.” The beautiful, sober figure of “Death in Destiny” came to us later, yet, although it was a much younger Goetzke who made the film.

After a pause, and close upon each other’s heels, pressed forward the minstrel of “The Nibelungs” and the “Knight Crusader of Decameron Nights,” and within the last few weeks we have seen the man again in “The Blackguard,” drinking and fiddling, fighting and reeling at the head of the revolutionaries, the one giant in that film of struggling pigmies.

It is characteristic of Bernhard Goetzke that he enters a film quietly, quite unobtrusively, with no flourish of trumpets and column of titles, but with his first entry he goes straight to the heart of the film, picks up the drama, holds it. Your eye finds him joyously, and follows him to the end.

When Goetzke is on the screen it is quite impossible to look at any one else.

He is a dangerous man for a star to partner with, as dangerous when he is in the distance, shadowed, right back stage, as when he is filling the eye of the camera in a close-up. He does not mean to be dangerous.

A quieter, more modest actor does not live. But the power of drama that is in him is too strong for complete repression, and only the fine actor, the actor of genius, can stand safely by his side.

The art of Bernhard Goetzke is an art of power half-restrained.

He has in a vast degree the quality of understanding both thought and emotion, of getting first of all into the very soul of his parts, becoming one with them, before he even attempts to suggest them to his audience.

Then he brings to bear upon them a finely perfected technique of expression, and allows the expressed character to filter through, as it were, in a fine, half-checked stream. His work is soft, and sure, and rather terrible in its strength. There is no faltering. There is no extravagance. But behind, and above, and all around it is the sense of hidden power.

If you watch Bernhard Goetzke closely, you will notice that he has reduced immobility to a fine art. He knows, more than any other actor, how to do nothing beautifully.

He makes few gestures, with the result that every gesture, when it comes, is weighty and fraught with dramatic power. He will not stir a little finger without good reason, but that little finger, when it does move at last, can bring down mountains.

The gods have given him a strange, sombre and very magnetic face. It changes little ; only the eyes reflect passing moods. Deep eyes, hypnotic in their level gaze. Mysterious eyes, holding you.

The immobility of that face, above the sculptural immobility of that figure, strikes you with an amazing sense of power restrained. It is a challenge, a promise half-revealed. And because it seems likely never to be revealed in full, it never palls.

The art of Bernhard Goetzke lies, not in what he does, but in what he is powerful enough not to do.

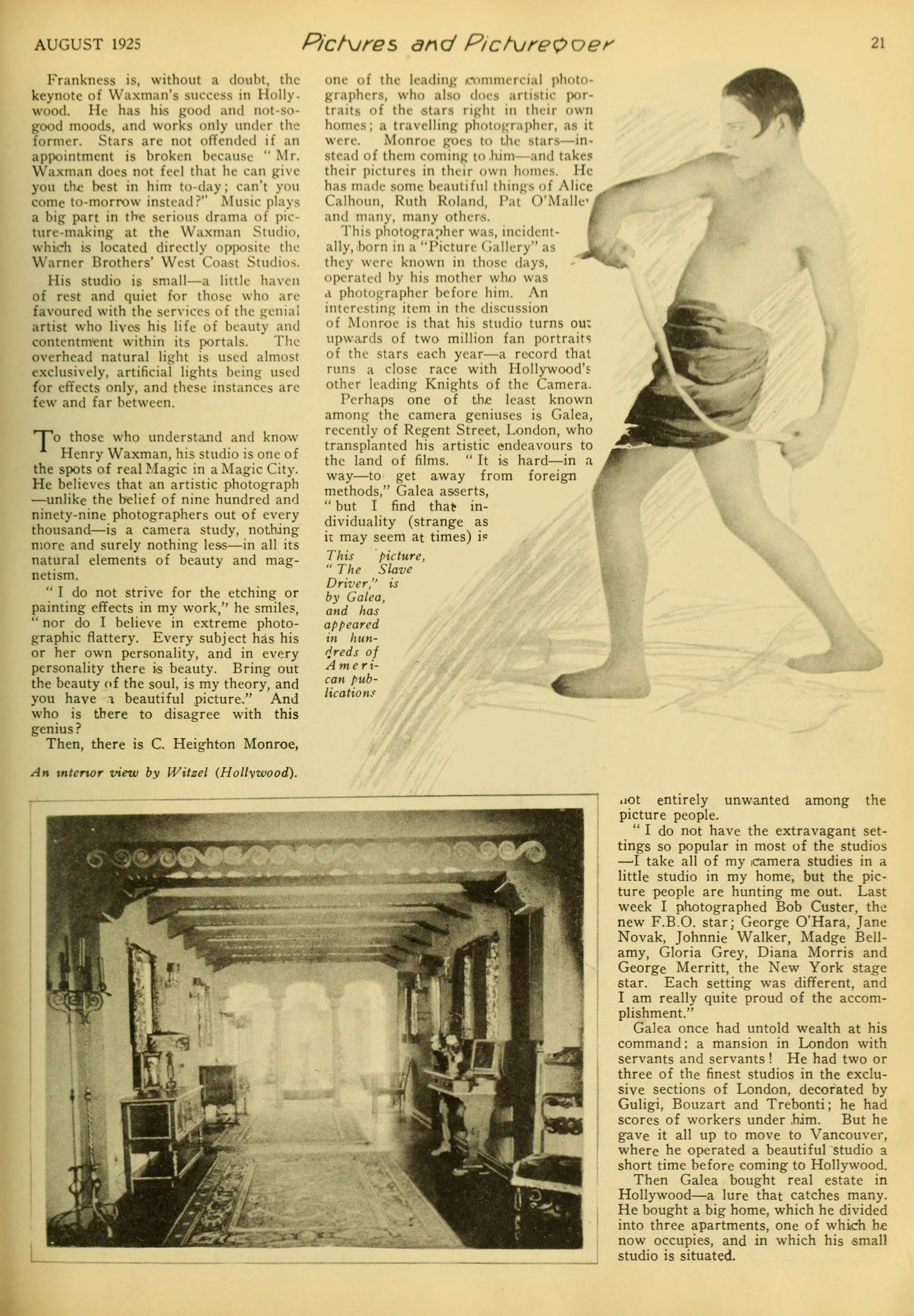

[a]

Bernhard Goetzke in “The Blackguard.”

Collection: Picturegoer Magazine, August 1925

---

The Art of… series:

- 1925–01 — Alla Nazimova

- 1925–02 — Adolphe Menjou

- 1925–03 — John Barrymore

- 1925–04 — Charles Chaplin

- 1925–05 — Pola Negri

- 1925–06 — Douglas Fairbanks Sr.

- 1925–07 — Leatrice Joy

- 1925–08 — Bernhard Goetzke

- 1925–09 — Mary Pickford

- 1925–10 — Ernst Lubitsch

- 1925–12 — Ian Keith