Renée Adorée — As She Is (1929) 🇺🇸

A complex personality is easy to get down on paper. Inhibitions and nuances of temperament make fair sailing on any typewriter. But the keys balk at the unaccustomed effort to describe a child. I mean Renée Adorée, who embodies the simplicity, the directness and naive honesty of childhood.

by Margaret Reid

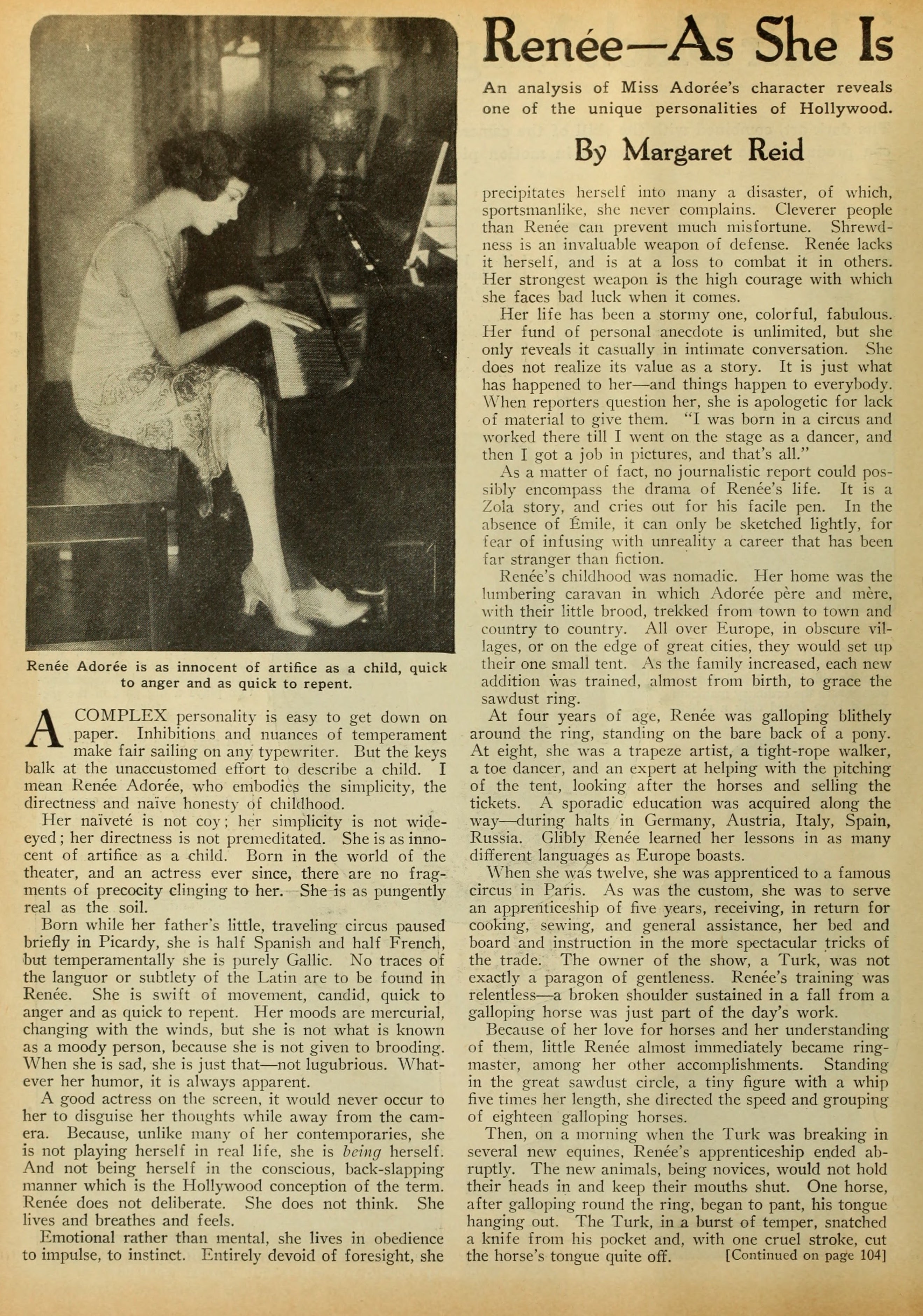

Her naïveté is not coy; her simplicity is not wide-eyed; her directness is not premeditated. She is as innocent of artifice as a child. Born in the world of the theater, and an actress ever since, there are no fragments of precocity clinging to her. She is as pungently real as the soil.

Born while her father’s little, traveling circus paused briefly in Picardy, she is half Spanish and half French, but temperamentally she is purely Gallic. No traces of the languor or subtlety of the Latin are to be found in Renée. She is swift of movement, candid, quick to anger and as quick to repent. Her moods are mercurial, changing with the winds, but she is not what is known as a moody person, because she is not given to brooding. When she is sad, she is just that — not lugubrious. Whatever her humor, it is always apparent.

A good actress on the screen, it would never occur to her to disguise her thoughts while away from the camera. Because, unlike many of her contemporaries, she is not playing herself in real life, she is being herself. And not being herself in the conscious, back-slapping manner which is the Hollywood conception of the term. Renée does not deliberate. She does not think. She lives and breathes and feels.

Emotional rather than mental, she lives in obedience to impulse, to instinct. Entirely devoid of foresight, she precipitates herself into many a disaster, of which, sportsmanlike, she never complains. Cleverer people than Renée can prevent much misfortune. Shrewdness is an invaluable weapon of defense. Renée lacks it herself, and is at a loss to combat it in others. Her strongest weapon is the high courage with which she faces bad luck when it comes.

Her life has been a stormy one, colorful, fabulous. Her fund of personal anecdote is unlimited, but she only reveals it casually in intimate conversation. She does not realize its value as a story. It is just what has happened to her — and things happen to everybody. When reporters question her, she is apologetic for lack of material to give them. “I was born in a circus and worked there till I went on the stage as a dancer, and then I got a job in pictures, and that’s all.”

As a matter of fact, no journalistic report could possibly encompass the drama of Renée’s life. It is a Zola story, and cries out for his facile pen. In the absence of Èmile, it can only be sketched lightly, for tear of infusing with unreality a career that has been far stranger than fiction.

Renée’s childhood was nomadic. Her home was the lumbering caravan in which Adorée père and mère, with their little brood, trekked from town to town and country to country. All over Europe, in obscure villages, or on the edge of great cities, they would set up their one small tent. As the family increased, each new addition was trained, almost from birth, to grace the sawdust ring.

At four years of age, Renée was galloping blithely around the ring, standing on the bare back of a pony. At eight, she was a trapeze artist, a tight-rope walker, a toe dancer, and an expert at helping with the pitching of the tent, looking after the horses and selling the tickets. A sporadic education was acquired along the way — during halts in Germany, Austria, Italy, Spain, Russia. Glibly Renée learned her lessons in as many different languages as Europe boasts.

When she was twelve, she was apprenticed to a famous circus in Paris. As was the custom, she was to serve an apprenticeship of five years, receiving, in return for cooking, sewing, and general assistance, her bed and board and instruction in the more spectacular tricks of the trade. The owner of the show, a Turk, was not exactly a paragon of gentleness. Renée’s training was relentless — a broken shoulder sustained in a fall from a galloping horse was just part of the day’s work.

Because of her love for horses and her understanding of them, little Renée almost immediately became ringmaster, among her other accomplishments. Standing in the great sawdust circle, a tiny figure with a whip five times her length, she directed the speed and grouping of eighteen galloping horses.

Then, on a morning when the Turk was breaking in several new equines, Renée’s apprenticeship ended abruptly. The new animals, being novices, would not hold their heads in and keep their mouths shut. One horse, after galloping round the ring, began to pant, his tongue hanging out. The Turk, in a burst of temper, snatched a knife from his pocket and, with one cruel stroke, cut the horse’s tongue quite off.

Renée, from her place in the ring, saw this and, with a scream of horror and fury, was at the Turk’s side in a moment. Snatching his whip with the wicked steel thong on the end of it, and wielding it with both muscular, little arms, she lashed out at her master in a frenzy. Beating him until he cowered in a corner, and then jumping on him with both feet, she was finally dragged away, a small virago, sobbing, between epithets, for her poor, mutilated horse.

Back in her father’s circus, the outbreak of war did considerable damage to their business. In order to keep the little troupe in food, Renée and her sister got work in a factory, wrapping bouillon cubes. Their earnings were about fifteen cents a day, with a penny extra for every additional thousand cubes they wrapped. Renée, unaccustomed to the close atmosphere, had fainting spells, and her sister worked with frantic speed to cover Renée’s lapses.

When the circus was playing a not very profitable engagement in Belgium, on the outskirts of Brussels, the German invasion came. Saving nothing but the clothes they wore, the family joined the other refugees in flight to a boat for England. On board there was a search for a woman spy. Renée was stripped and the skin taken off her back with alcohol, in the belief that there was a message on it in invisible ink. The spy was found elsewhere, and the bewildered Renée, her back stinging and raw, was allowed to proceed to England.

In London the first stirrings of conscious ambition began to trouble her. She slept in a real bed — and suddenly realized that the narrow bunks in caravans’ had been uncomfortable. She had glimpses of the London theaters, and realized that the carefree, wandering existence of her father’s circus was not the only possibility life offered.

Jobs as a dancer in London shows — an offer from Australia — running away from London — packed aboard a transport bound for Halifax — landing in New York because of the famous Halifax disaster — detained in the immigration offices — shipped to Canada under guard — sharing a seat in a tourist train with a muttering Chinaman — arriving in Vancouver ten days before the Australian boat was to sail, with just enough money to buy one meal a day — sleeping in the draughty station at night. Only fifteen years of age, yet she wasn’t frightened and, being magnificently healthy, survived without so much as a cold, although it was the middle of a bitter winter.

After a few months in Sydney, she returned to New York and worked there for some time, dancing and singing. Spotted by Louis B. Mayer, she was signed for pictures and has been a Hollywood luminary ever since.

Mélisande, in The Big Parade, is still the finest work she has done. Some day some wise person may be inspired to cast her in John Masefield’s Tragedy of Nan, and then her Mélisande would be topped. But things will not occur through any coercion on Renée’s part. She has not the gift of salesmanship. Around the studio she is The Frog, adored by the help, depended upon by the officials to jump in anywhere and save a picture from failure.

She lives in a shabby, rambling bungalow on an unfrequented country road near the sea, having moved there from a stucco mansion which she bought impulsively and loathed for its blatant newness. She loves old houses, old furniture. Her present home is small and sunny, unpretentiously comfortable, the house surrounded by an acre of ground on which grow avocados, berries, grapes, fruit trees, vegetables, flowers — all planted in charming confusion. Her ménage is polyglot, a German cook, Indian maid, Polish chauffeur, Chinese chow dogs, Persian cats. An aviary, forever being populated anew by prolific canaries, is one of her dearest possessions. A canny Irish lawyer looks after her finances and allows her only a moderate income, knowing her airy prodigality with money.

Like most families who have faced adversity together, the Adorées are passionately devoted. On Renée’s dressing table is a picture of her mother — a beautiful, delicately featured woman. Renée writes to her regularly, and has always provided for her comfort.

No laughter, when she is in high spirits, is more infectious than Renée’s. She is ingratiating, gamin. Her humor is broad and she loves practical jokes. She seldom smiles, without laughing outright. A group calling themselves, for no special reason, the “unholy four,” is composed of Renée, Ramon Novarro, Ronald Colman, and Charles Lane. Their diabolic function is to attend neighborhood movies together, explore little-known parts of Los Angeles, or just to sit and talk. With these cohorts, Renée, whose physical magnetism rates high, has the status of a boy, a good, little sport, a regular.

Although unhappiness has dogged her personal life, it has left no taint of bitterness — only a pervading wistfulness of which she is unconscious. Elemental in the honesty of her emotions, in her enthusiasm for life and her eager love of people, loyal and kind, devoid of malice, there is something gallant about her. And something a trifle pathetic, because of her consequent defenseless exposure to the political intrigue of Hollywood.

She ought to be a star, but it is doubtful if she ever will be. Skilled purveyors of personality get electric lights before Renée, who has plenty, but doesn’t throw it around.

Renée Adorée is as innocent of artifice as a child, quick to anger and as quick to repent.

Renée Adorée’s life has been a stormy one, colorful, fabulous, says Margaret Rcid, who modestly declares that no journalistic report could encompass the drama of Renée’s life. However, in the story opposite, you will be startled by its high lights.

Photo by: Clarence Sinclair Bull (1896–1979)

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, December 1929