Ramon Novarro — As He Is (1928) 🇺🇸

He is twenty-seven years old. At times his sane wisdom would befit a savant of eighty. Again, he might be boisterous, naïve twelve. Not a volatile person, he is, nevertheless, a varied one.

by Margaret Reid

There is in him a wealth of, as yet, untouched possibilities. Since leaving Rex Ingram’s patronage he has been, in the main, unfortunate in the mediocre vehicles selected for him. At all times he has contributed smooth, dramatically sound performances. The misfortune does not lie in the fact that he is difficult to cast. This he is not, for — almost alone of his contemporaries — he is equally at ease in broad comics or in romantic tragedy, and in all the half-tones of drama lying between them. The misfortune is that so much more should be made of his ability, than is utilized in adventure stories and Alger-flavored heroics.

At one time a dancer, he was discovered by Rex Ingram. The occasion was a program at the now extinct Little Theater of Hollywood. Ramon was the principal in “The Spanish Fandango,” a pantomime. Between engagements he was eeking out what he bravely called a living, by what extra work he could obtain at the studios. Ingram at once sensed the potentialities of the fiery youngster in the Fandango. He sent for him, gave him screen tests, and while waiting to begin work, lent him to Ferdinand Pinney Earle for The Rubaiyat — released five years later as A Lover’s Oath — and finally brought him almost to immediate fame in Rupert of Hentzau and The Prisoner of Zenda.

Novarro comes of sturdy middle-class Mexican stock — the bourgeoisie that has pride of lineage, is comfortably secure, tranquil, and. conservative. His father was a successful dentist, until the revolution wiped out his practice and the family fortunes, and made necessary their departure from Mexico. One of ten children, Ramon is second in line, having an older brother.

Hollywood knows little of Novarro’s private life. He is never seen at the favorite haunts of the film colony. He doesn’t accept invitations and has been to the Mayfair Club but once, and then only under pressure. When he does go out it is to an opera or concert, to a little Mexican cafe down in the Plaza, a play, or to the obscure Spanish theater. He loves anything pertaining to the theater. His particular passion of the American stage is the mad humor of Ed Wynn.

Almost his only close friends among the profession are Ronald Colman and Herbert Howe. The German director, Murnau [F. W. Murnau] — himself more or less a recluse — is a recent acquaintance. The director’s favorite music is Spanish folk-music, and his interest in Ramon’s unlimited knowledge of it never flags. One of his most fervent admirers and boosters is Kathleen Key, who has worked with him in several pictures. Principally his friends are of the Spanish and Mexican colonies. To them he is not Rah-mon, or Ray-mon, Novarro, the famous star, but Rra-moan, the charming and brilliant son of Poctor Samaniegos.

Ramon’s love of family is intense. He has always lived with his people, instead of in bachelor quarters. In the enormous old house, in a sedate section of Los Angeles, he has with him his entire family, with the exception of two sisters, who are nuns. One of these is in a Mexican convent, the other a Sister of Mercy in the Canary Islands.

When he travels he takes along part — or all, if possible — of his family. When away from her, he misses his mother with boyish forlornness. They all share his life, and with them he is content. He adores them. He watches over his sisters with vigilant devotion. Recently he set up two of his brothers in business. They devised a new coffee substitute, and he backed and established them in offices in Los Angeles. Whenever he goes out, some of his family accompany him.

On a journey or in public, his family are timid of the celebrity attached to them, because they are Ramon’s relatives. It is against their wishes, and in considerable bewilderment, that they are lined up and photographed or interviewed. They are all of a most retiring nature.

Every Novarro premiere is a gala occasion in the Samaniegos household. Most celebrities, it must be noted, order seats and then ask the publicity department to look after the family, themselves preferring to appear in more glittering company.

On Novarro first nights there is the row of fifteen or twenty seats for the immediate family and close friends or visiting relatives. And Ramon, glowing with pride, shepherding his brood into the seats with meticulous gallantry. The brothers, thrilled and nervous, the sisters — in ruffled white with broad sashes — shy and excited. All the family spellbound at every gesture of this Ramon of theirs upon the screen, dying to applaud, but that Ramon has sternly forbidden. During intermission are elaborate introductions: “This is my mother — my father — and this, my sister.”

There have been rumors, at various times, of Ramon’s contemplated retirement to a monastery. These he denies. He has no intention of becoming a priest, although he is deeply religious. He has studied every existing and extinct religion, and is familiar with their every belief and ritual. He remains a devout Catholic, believing with immutable faith. Never, however, does he make conversation about it.

Much space has also been devoted to his singing and his intentions of deserting the screen for the concert stage. He studies under Louis Graveure, one of the most famous singers and teachers in the country. Until recently Ramon sang every Sunday in the choir of the little church where the Samaniegos family worship. His voice is a tenor of extraordinary sweetness and power. It is very possible that when he wearies of the screen, concert work will be his next field.

Music is the rhythm of the world for Ramon. He is never satiated, attending every recital, subscribing to the operas and symphonies. He is one of the few stars owning a box at the Hollywood Bowl. Both technically and emotionally, his knowledge of music is vast.

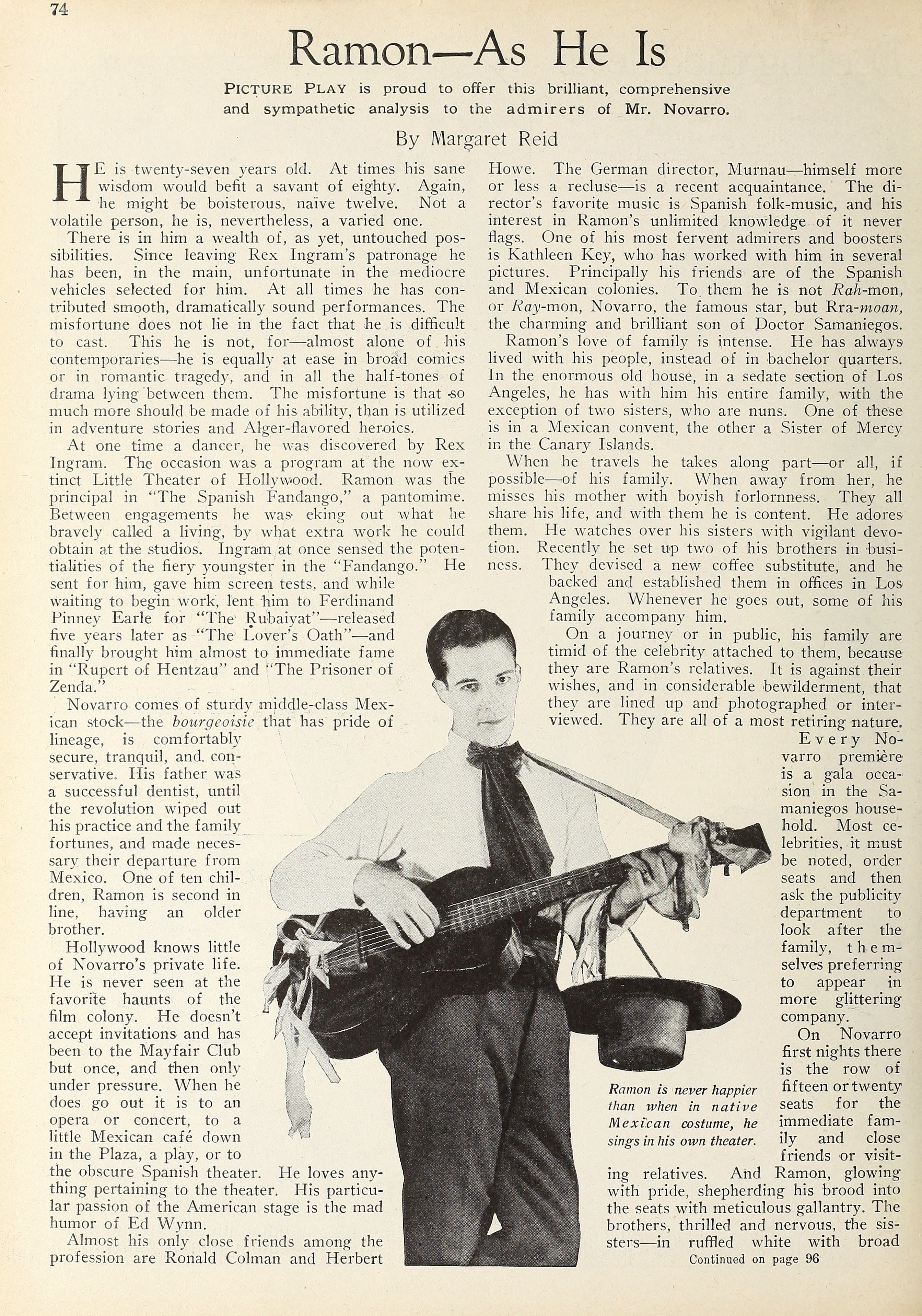

No story — indeed, no mention — of Ramon is complete without reference to his private theater. This is called his hobby, but is really his passion. To make it possible he had an ell built onto his house. It seats barely a hundred people, but the stage is proportionally large and has every facility, slightly modified, of a professional house. It is called the Theatre Intime Novarro. His own orchestra of Mexican musicians is under contract to him. The intricate lighting arrangement was devised by an electrical engineer, and is the most elaborate of any amateur theater in America.

In his theater Ramon presents mostly old Spanish plays and sketches. Some sketches he writes himself. Many are musical. The production is always faultless in detail, beautifully costumed and skillfully presented. Often only Ramon appears. At other times some of his family or friends participated. Only close friends are invited to join the family in the audience. The theater is for their delectation and Ramon’s pleasure.

A naturally conservative person, this is Ramon’s one extravagance, and here he spares nothing.

He is an unexpected revelation to strangers who know nothing about him. Joan Crawford, when cast opposite him in Across to Singapore, was frankly apprehensive. She didn’t want to work with him; would, she was sure, be bored. The first day on the set he taught her the new five-step.

It is an anomaly that Ramon is known among his confreres as being “good fun.” His sensitive, almost aesthetic, cast of features — the aura of romance that hangs over him — belie the coltish boisterousness which indicates his high spirits. His humor is not subtle — it is the broad comics of an ebullient child. At such times he plays hilarious jokes, and his antics are as irresistible as the pranks of a puppy.

He tells foolish, ribald stories with such keen delight that you laugh, even if you don’t get the point. You laugh really at him, rather than with him. In such moods he is so naïve, so unconsciously absurd and lovable, as to create dangerous stirrings in any maternal instincts that happen to be about.

He loves to teach his studio friends remarkable Mexican card games. Games that require much shouting, and the penalties for the loser are such quaint forfeits as having his eyelashes jerked, or his nose tweaked by the winner. Just when the novice is learning how, and beginning to win, Ramon immediately remembers another game to teach him. With the naïveté of a small boy he likes to win, and his frank hilarity in doing so is delightful.

His one streak of sophisticated humor is his gift for mimicry. With a lightning metamorphosis of expression and manner he gives uncanny burlesques of whatever subject is requested. It is to be hoped that this talent will some time be presented on the screen.

He would like to write the story of his life and use it as a picture. There is a possibility that this idea will materialize. He would also like to do Jennifer Lern, by Elinor Wylie, playing therein the role of the exquisite young prince who was a pastry cook. In delirious visions he dreams of this production, directed by Ernst Lubitsch, with Lillian Gish as Jennifer.

His admiration for Lillian Gish amounts to reverence. To him she is the supreme artist. Whenever possible he slips over to her set and stands in a corner, watching her work. Should occasion arise to speak to her, he is bashful, almost gauche. This the Ramon who can be so contained and suave.

—

Ramon is never happier than when in native Mexican costume, he sings in his own theater.

—

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, August 1928