Casting Directors — Theirs Is Not a Happy Lot (1928) 🇺🇸

Not long ago a woman entered the Paramount studio carrying a brick — a nice, red brick, which had eight sharp corners and was rough. She glided toward Fred Datig, casting director, with all the grace of a panther entering her lair.

by A. L. Wooldridge

“I have come,” she said, “to get work. I need it. You must give it to me!” There was a snap in her voice, a ring of finality and determination, which was ominous. She toyed with the unit of building material held in her throwing hand. A threatening look was in her eye.

“I have come here” again and again,” she continued, “seeking a chance to make a living. Now I have no money left. What are you going to do about it?”

Mr. Datig looked at the woman and recalled having seen her before. He did not recall ever having given her employment. Somehow she was not just the type to find regular work; in some way had seemed never to fit in. He knew nothing of her straitened circumstances, nor her struggle for daily bread. Furthermore, roles are not given to women merely because they need them. Mr. Datig had nothing to offer her unless — well, unless she was intent on hurling that brick. He doesn’t like to dodge bricks. So he began to parley.

“What kind of work can you do?” he asked.

“I can play any kind of role.”

“How much pay do you want?”

“Whatever is commensurate with the work.”

He studied her a moment, appeared to become lost in meditation, then suddenly said, “Let’s go out to the Bebe Daniels set.”

She arose and followed him from the room, still carrying the brick. She was still holding onto it when Mr. Datig found a policeman, who disarmed her and led her to an exit.

The incident is indicative of what transpires with painful regularity in casting offices. Into them come at times penniless, discouraged, dejected men and women who are on the verge of suicide. Before the outer wicket, too, stand the men who have failed, the derelicts who believe that pictures afford a means of making an easy living. A man who had been well up in the profession, but who in recent years had begun to slip, was being considered for a fairly good role. He was not a “whiner,” not a fellow with a hard-luck tale. He had accepted hard knocks with a smile and without a murmur. Now it appeared he was to get another chance. He stood before the casting-office window, eager, anxious, but dignified. But only an hour before, the studio officials had rejected his name and awarded the role to another.

“It was up to me to tell him,” Mr. Datig said, “and I saw tragedy creep into his face. His lips went white. He said not a word in protest, but I sensed that this blow would snap what was left of his spirit. It was the last straw. The fellow looked at me and smiled.

“‘Thank you,’ he said softly, and turned to go.

“‘Hold on!’ I called. ‘Wait till I talk to the head office a moment. Sit down a bit!’

“I went up front and said abruptly, ‘There’s a man out there; who will be dead by morning if he doesn’t get the part he’s up for. He can play it. Let’s give him a chance!’ “They told me I was getting soft-hearted, that suicide threats were made every day, but they didn’t amount to much.

“‘But this man hasn’t threatened suicide!’ I protested. ‘He isn’t that kind. Yet it is written in his face. He means it.’

“My pleading availed nothing and I had to deliver the ultimatum. Next morning the story was in the newspapers — a quiet spot beneath a palm in Westlake Park, a note of explanation, an automatic and — rest. His blood was not on my hands. I had done all I could, but the thought of how a life might have been saved merely by giving a role in a picture, remained for days in my mind.

“Fifteen years I have been casting for pictures. I have no friends. I cannot afford them. They say I am hard-boiled. I wish I were. I do have to steel myself against pitiful tales. It isn’t easy to do. A woman of refinement will come in here. ‘I’m hungry,’ she will say. ‘I’ve had no food to-day. I have been evicted from my room. There is no place to go — no one to whom I may turn. I have a child, who is hungry. My God, Mr. Datig, I’m desperate.’

“I can give her from my own pocket the money with which to buy something to eat, but that relieves the condition only slightly. Then what? Heaven only knows. A man appeared at the window not long ago and said, I came from Honolulu to get work in pictures. I’m tired, now, of asking for it. You find something for me!”

“‘We didn’t send for you,’ I told him. ‘You’d better go back to Honolulu. There’s no demand for your services here, and frequently I’ve told you so.’

“Now, without doubt, that man went away believing I entertained a personal dislike for him, which was not true. We simply did not need him. In fact, one of the hardest things I encounter is keeping persons from thinking I dislike them, because I do not use them more often in pictures. You probably have read of the prison executioner as ‘The Man Who Walks Alone.’ Let me tell you that a casting director is virtually in the same position. The favors you do are soon forgotten, but hatred and bitterness are nurtured and long remembered.

“I’ve no idea, of course, the number of persons in this business who think they would like to be a casting director and hand out jobs to their friends. But you can’t have friends in this position — and keep them. You can’t pass out the jobs they want, when you know the applicants are unsuited to the roles. I have friends, yes! But away from my office.”

As the director talked, he was interrupted by calls from a battery of telephones. Yet nothing perturbed him. He spoke kindly, wasted no words, but left no opening for argument.

“I am constantly looking for new talent,” he continued presently. “It is true that there is a surplus of players in Hollywood, yet we want new stars. I discovered Laura La Plante when I was casting for Universal. Irving Thalberg, then with that company, did not show enthusiasm when I mentioned her as a girl with possibilities. But I cast her in bit after bit, and was convinced that some day she would arrive.

“Eventually Laura was signed. She is the best box-office bet Universal has today. Likewise I picked Janet Gaynor from the mob and now she is being starred. There is need of young men, too, for leading roles. The motion-picture industry is almost at the point where it would pay a bounty on the heads of eligible young men. But again I warn you — latent talent must be there. If it is, we’ll bring it out.

“The satisfaction of seeing your discoveries succeed compensates, in a measure, for some of the unpleasant things which happen in the casting office, but it cannot wipe from one’s mind the memories of those sad and wistful faces which come to the window and turn away when employment is denied. Nor does it erase the regret for jobs withheld, which would have prevented suicides.”

The experiences of Fred Datig are not dissimilar to those encountered by casting directors in all the Hollywood studios. None has forgotten the suicides more; or less attributable to the inability of players to find employment.

“A handsome, gentlemanly young fellow, whom I had known for a long time, came to me one day,” said Robert Mclntyre, for years casting director for Metro-Goldwyn, and who is now production manager for Samuel Goldwyn. “He needed work badly. He was just about at the end of his string.

“‘Harry,’ I said, ‘there isn’t a thing here, except a bit which will pay fifteen dollars a day. I could hardly offer you that.’

“I’ll take it!’ he cried.

“‘But you are worth something better,’ I urged. I don’t like to put you down that low.’

“‘I’ll take it!’ he repeated. ‘I must eat.’ His face was pinched. Lines of care were showing. I gave him the part. Next day the picture was postponed for two months, and the following morning I read the story of Harry in the newspapers. It was suicide.

“One day I drove up to the studio gate along about sundown. I opened the door to shout some instructions, when a man stepped in my car and sat down. He seemed to think I had stopped to pick him up. So I let him ride. The conversation went something like this:

“‘Work in pictures?’ I asked.

“‘Yep!’ he replied. ‘I’m an actor.’

“‘Doing much lately?’

“‘Nope! Just been trying to get a job out here. They turned me down — those young bucks in Bob Mclntyre’s office.’

“‘See Mclntyre?’

“‘Nope! But he’s as bad as all the rest. No good, that feller.’

“I let him out, without revealing my identity. But I learned about myself from him.

“They have come up to the casting window, have become enraged when they got no work, and tried to punch my assistants in the face.” Students of human nature, these men — all of them.

A sad-faced young man walked up to Gus Corder in the casting office of Metro-Goldwyn.

“Good-by, Mr. Corder,” he said.

“Going away?” the director asked.

“Yes. Going on a long, long journey. Nobody wants me. So I’m going to kill myself to-night.”

Corder looked at him through the corners of his eye, and made up his mind that the fellow was only seeking sympathy. So he replied, “Good-by, old man. Make a good job of it while you’re at it. The world has no use for quitters.”

“Well, sir,” Mr. Corder said, later, in referring to this incident, “the fellow looked dazed for a moment, then turned and moved slowly out of the room. Did he commit suicide? He hadn’t the nerve. He hung around the studio for a while and eventually disappeared for good.

“A case of another kind was a little woman who appeared before me, her face drawn and haggard. She had once been beautiful. But lines were coming in her face. Something was wrong.

“‘What’s the matter, my dear?’ I asked.

“‘Nothing!’ she replied as bravely as she could.

“‘I know better. There are red blotches on your lips. What have you been doing?’

“It took me a long time to get the story, but eventually it came, little by little. She had despaired, and in a fit of despondency had drunk a deadly lotion. Quick action by police surgeons saved her life.

“But here she was, an old-young woman with talent, alone and afraid of the world. She needed help, friends, and counsel. I talked to her a long time. Then I asked a director to use her. This little act encouraged her. She got a new grip on herself. She’s working to-day and millions of persons know her. Tell you her name? Not for any amount of money!”

Into the ears of these men are poured the sorrows of Hollywood. Upon them is worked every trick and scheme to get work. To them falls the task of diplomatically disposing of applicants, who come with notes from influential friends. On their shoulders rests the responsibility of choosing players who will be a credit to the cast. They are the buffers between the executive offices and the gate-crashing mob. If you think it’s a pleasant task, you’re all wrong.

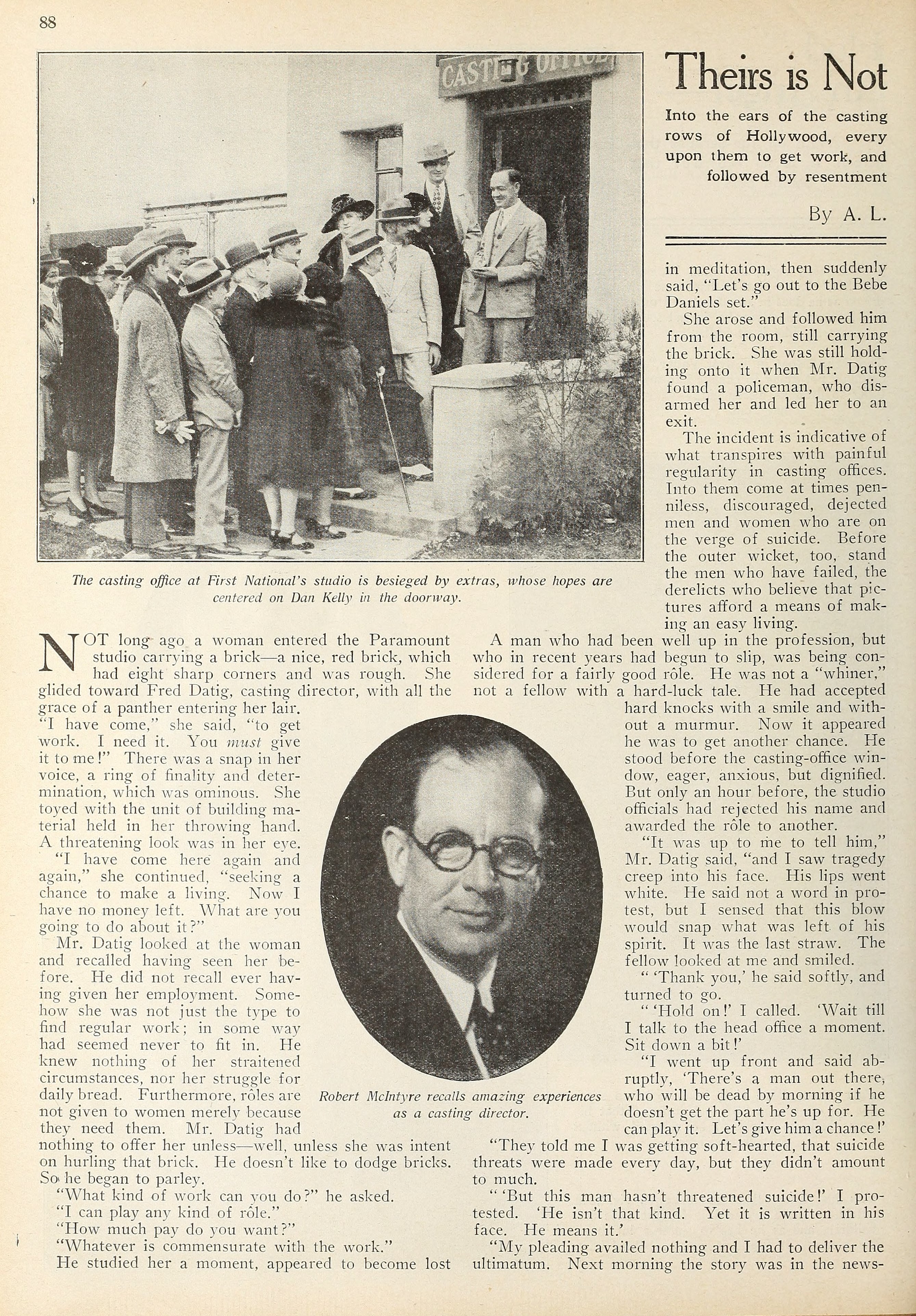

The casting office at First National’s studio is besieged by extras, whose hopes are centered on Dan Kelly in the doorway.

Robert Mclntyre recalls amazing experiences as a casting director.

Fred Datig, Paramount ‘s casting director, admits he has friends, but they are not among those who apply to him for work.

Ginger, the dog actor, is as eager for a role as his fellow players among the human extras.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, July 1928