Mae Murray — The Temperamental Blonde (1921) 🇺🇸

It looked like the Rubiayat beside the subway; Bagdad, New York; a caliph on an omnibus; Scheherezade dodging a Ford. This impression of the Famous Players studios will be better understood when it is chronicled that George Fitzmaurice was spooling a Turkish-harem-and-mosque romance on the one side, with Dorothy Dalton spurning the villain’s very modern advances in a Riversidewise apartment set on the other side of the barn-like building. The entering guest, then, was reminded of “The Arabian Nights” with an O. Henry obbligato: Fifth Avenue, Cairo, and divers similar conflicting thoughts.

by Malcolm H. Oettinger

“You’re lucky if you find Miss Murray working,” my studio guide assured me, as we dodged in and out among wires, Klieg lamps, backings, and miscellaneous odds and ends of scenery. “She used to be in the Follies, y’know, and when they’ve once been in the Follies, you might as well try to film the telephone directory as get them on the set before twelve.”

It was eleven. We found our circuitous way to Mr. Fitzmaurice. He was directing two electricians.

“That moon,” he said, “must be smooth, calm, steady, not like a spotlight. You understand? Dim it. Dim it!”

He turned to me, and showed me the photograph in his hand. It was a still of a scene that had been shot in Florida for the picture now in course of construction, and it was his task, and that of the electricians to “match up” the moonlight they had registered there, with the moonlight streaming in through the window of the set.

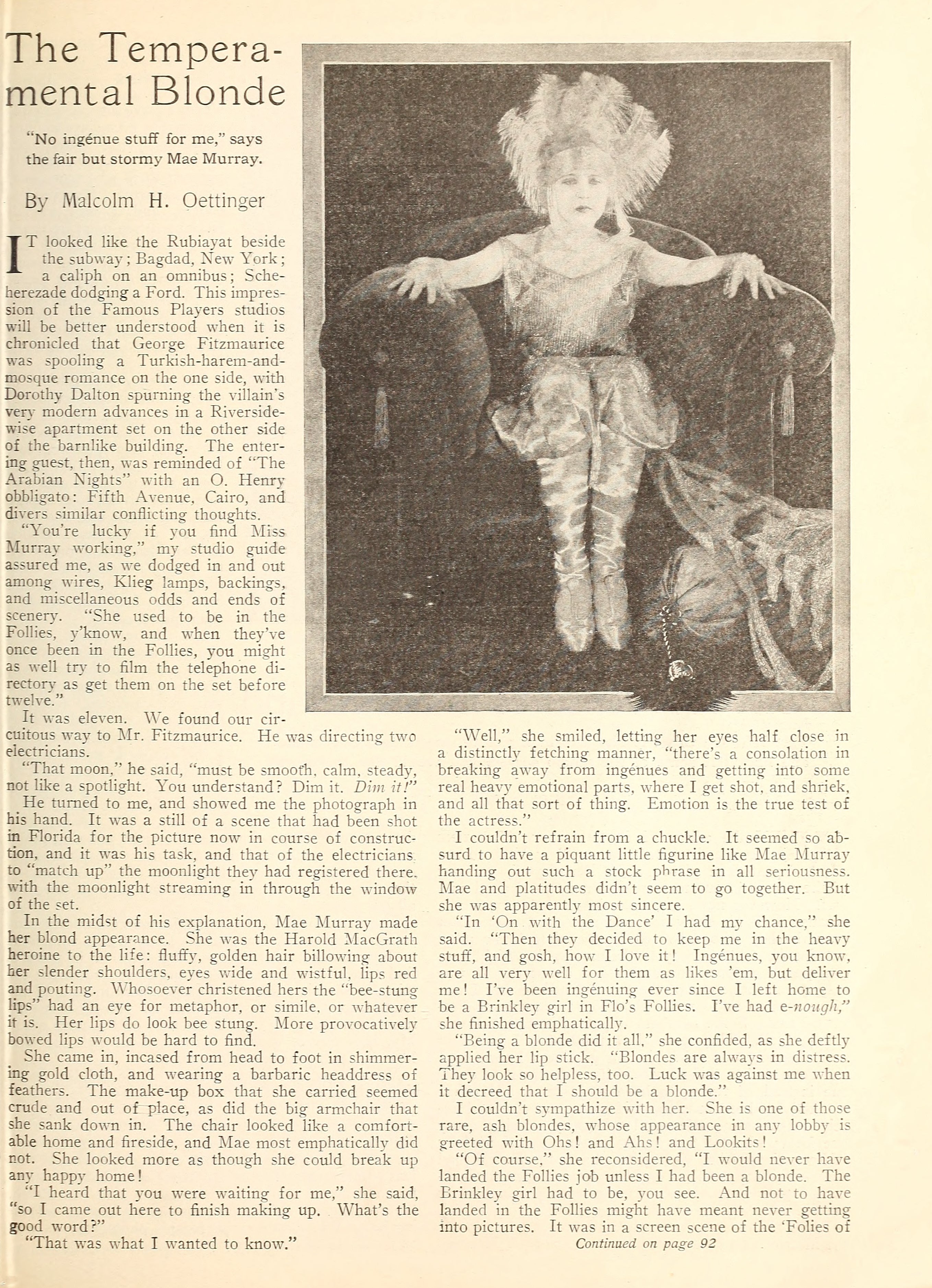

In the midst of his explanation, Mae Murray made her blond appearance. She was the Harold MacGrath heroine to the life: fluffy, golden hair billowing about her slender shoulders, eyes wide and wistful, lips red and pouting. Whosoever christened hers the “bee-stung lips” had an eye for metaphor, or simile, or whatever it is. Her lips do look bee stung. More provocatively bowed lips would be hard to find.

She came in, incased from head to foot in shimmering gold cloth, and wearing a barbaric headdress of feathers. The make-up box that she carried seemed crude and out of place, as did the big armchair that she sank down in. The chair looked like a comfortable home and fireside, and Mae most emphatically did not. She looked more as though she could break up any happy home!

“I heard that you were waiting for me,” she said, “so I came out here to finish making up. What’s the good word?”

“That was what I wanted to know.”

“Well,” she smiled, letting her eyes half close in a distinctly fetching manner, “there’s a consolation in breaking away from ingénues and getting into some real heavy emotional parts, where I get shot, and shriek, and all that sort of thing. Emotion is the true test of the actress.”

I couldn’t refrain from a chuckle. It seemed so absurd to have a piquant little figurine like Mae Murray handing out such a stock phrase in all seriousness. Mae and platitudes didn’t seem to go together. But she was apparently most sincere.

“In On with the Dance I had my chance,” she said. “Then they decided to keep me in the heavy stuff, and gosh, how I love it! Ingenues, you know, are all very well for them as likes ‘em, but deliver me! I’ve been ingénueing ever since I left home to be a Brinkley girl in Flo’s Follies. I’ve had e-nough ,” she finished emphatically.

“Being a blonde did it all,” she confided, as she deftly applied her lip stick. “Blondes are always in distress. They look so helpless, too. Luck was against me when it decreed that I should be a blonde.”

I couldn’t sympathize with her. She is one of those rare, ash blondes, whose appearance in any lobby is greeted with Ohs! and Ahs! and Lookits!

“Of course,” she reconsidered, “I would never have landed the Follies job unless I had been a blonde. The Brinkley girl had to be, you see. And not to have landed in the Follies might have meant never getting into pictures. It was in a screen scene of the Follies of 1915 that Jesse Lasky saw me. I went West to do some pictures for him then. And if I hadn’t gone West I shouldn’t have met Bob Leonard [Robert Z. Leonard], which would have meant that I might have missed a perfectly good husband. So, after all, perhaps I’m glad that I’m a blonde.”

She was doing “The Plow Girl” in the picture of that title when she first met Mr. Leonard. And you must take her word for it that it was a case of L. at F. S. And what is more, they are living happily, strange though this must seem to those wise-acres who speak of “these incompatible temperaments.”

“And it is lots of fun,” said Mae, daubing her neck with a gigantic powder puff, “working under Bob. He is some little director.”

As a victim of the sex-titled picture play, Miss Murray took up an active cudgel against the practice of tacking luring labels on otherwise circumspect photo plays.

“At Universal I did some six or eight pictures, and the one thing I am thankful for is that I didn’t do more, because when they got to the last the title had become Her Body in Bond. The board of censors alone knows what the next one might have been called.

“If pictures can’t draw through merit and real magnetism, it hardly seems justifiable from any sane point of view to wish such hectic titles as that on them, and scare a lot of people away. I’m for pictures strong, and I’m against that sort of exploitation of them with equal emphasis.”

But her conversation didn’t run entirely along such serious channels. For instance, she assured me that life in the Follies wasn’t the champagne-colored existence that popular fancy paints it. Far from it, says Mae.

“Ann Pennington and I shared a dressing room together. We drank milk night and day to get pleasingly plump. We never saw the primrose path winding anywhere near the Follies’ stage door. Ann’s a great little pal. We still drink milk together whenever we meet, just to recall our Follies days.

“There was a training to be derived from that musical-comedy work, too. You know how gracefully every girl in a Ziegfeld show carries herself. You’ve noticed that ball-bearing glide, haven’t you? Well, it’s a cultivated art. Calisthenics, practice, and Ned Wayburn are the recipe. Ned isn’t with Flo any more, but he was a wonder in his day. And it was there that I acquired whatever grace I possess. Then, too, I did a lot of interpretative dancing in the Follies. That aided me enormously when I came to the screen.”

“You will insist upon being emotional, won’t you?”

She smiled and pouted.

“I want to do strong, heavy drama,” she said. “I want to be one of those high priestesses of passion. I want to do stories that let me suffer and sacrifice and struggle and — love. I like the sort of play that gives me the tragic touch in the earlier parts and then winds up with a strong climax — and a happy one. Give me a part with depth and emotion and feeling, and I’m happy,” said Mae, with her big eyes looking at me earnestly.

“Don’t you think I could do that heavy stuff?” she asked suddenly, her carmined lips curving coaxingly.

There was, of course, only one answer that a susceptible young man could make to such a lovely questioner.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, April 1921