Hobart Bosworth — A Man Who Refused to Die (1921) 🇺🇸

If you knocked about from pillar to post in Hollywood for a couple of months meeting stars and directors, supers and camera men, juveniles and ingénues, carpenters and critics, you would find that the race is almost always to the swift, contrary though that may sound.

by Malcolm H. Oettinger

The stars are young, beautiful women, and young, handsome men, the majority of them little more than girls and youths. The average star is a personable, friendly, carefully dressed individual with youth and a certain definite irresponsibility about life and its problems. You will find it exceedingly difficult to induce one of these spotlit creatures to discourse intelligently on anything foreign to diffusers, fat parts, or upstaging. You will find them a singularly easy-going set — worried neither by the rising cost of gasoline nor even the income tax.

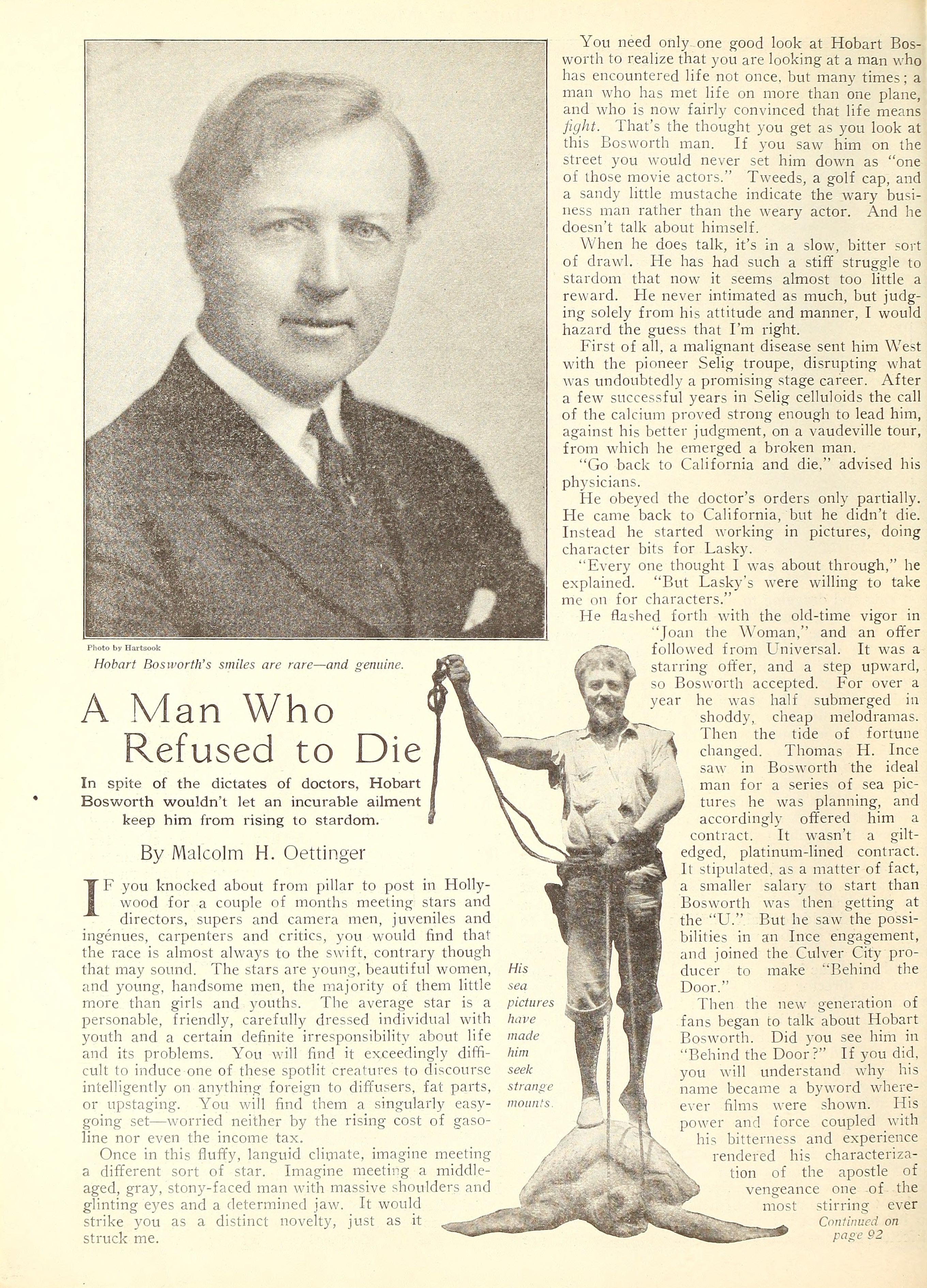

Once in this fluffy, languid climate, imagine meeting a different sort of star. Imagine meeting a middle-aged, gray, stony-faced man with massive shoulders and glinting eyes and a determined jaw. It would strike you as a distinct novelty, just as it struck me.

You need only one good look at Hobart Bosworth to realize that you are looking at a man who has encountered life not once, but many times; a man who has met life on more than one plane, and who is now fairly convinced that life means fight. That’s the thought you get as you look at this Bosworth man. If you saw him on the street you would never set him down as “one of those movie actors.” Tweeds, a golf cap, and a sandy little mustache indicate the wary business man rather than the weary actor. And he doesn’t talk about himself.

When he does talk, it’s in a slow, bitter sort of drawl. He has had such a stiff struggle to stardom that now it seems almost too little a reward. He never intimated as much, but judging solely from his attitude and manner, I would hazard the guess that I’m right.

First of all, a malignant disease sent him West with the pioneer Selig troupe, disrupting what was undoubtedly a promising stage career. After a few successful years in Selig celluloids the call of the calcium proved strong enough to lead him, against his better judgment, on a vaudeville tour, from which he emerged a broken man.

“Go back to California and die,” advised his physicians.

He obeyed the doctor’s orders only partially. He came back to California, but he didn’t die. Instead he started working in pictures, doing character bits for Lasky.

“Every one thought I was about through,” he explained. “But Lasky’s were willing to take me on for characters.”

He flashed forth with the old-time vigor in Joan the Woman, and an offer followed from Universal. It was a starring offer, and a step upward, so Bosworth accepted. For over a year he was half submerged in shoddy, cheap melodramas. Then the tide of fortune changed. Thomas H. Ince saw in Bosworth the ideal man for a series of sea pictures he was planning, and accordingly offered him a contract. It wasn’t a gilt-edged, platinum-lined contract. It stipulated, as a matter of fact, a smaller salary to start than Bosworth was then getting at the “U.” But he saw the possibilities in an Ince engagement, and joined the Culver City producer to make Behind the Door.

Then the new generation of fans began to talk about Hobart Bosworth. Did you see him in Behind the Door? If you did, you will understand why his name became a byword wherever films were shown. His power and force coupled with his bitterness and experience rendered his characterization of the apostle of vengeance one of the most stirring ever projected on the silversheet. In Behind the Door he had to play an oldish man who had suffered. It was easy for him, he told me.

“When people tell me how good that was or the next one or the one after that, I smile to myself and think of what the doctors told me to do. It hasn’t been any soft snap for me, this starring game. I like to do pictures just as much as I ever did, of course. I was born a trouper, and a trouper I’ll die. But don’t, please don’t let any one tell you it’s an easy life! I’ve lived through enough to fill three other lives as well. And I’m not young any more.” After his sea stories with Ince, Bosworth went over to the J. Parker Read forces — on the Ince lot — and starred in Bucko MacAllister, MacNeir, and His Own Law.

After that came The Brute Master, a Hodkinson picture, which was considered by some the finest work of his career, but those who have already seen him in A Thousand to One, a new J. Parker Read production, declare that that is Bosworth at his best.

His comeback should be enough to give even a Jess Willard hope.

Hobart Bosworth’s smiles are rare — and genuine.

Photo by: Fred Hartsook (1876–1930)

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, April 1921