House Peters — Straight from the Shoulder (1921) 🇺🇸

Some one said he was making a picture for Colonel Selig, the same Selig who columbused the modern serial by unfolding the famed adventures of Kathlyn Williams in the Edendale jungles. You remember, even if you are not very old.

by Malcolm H. Oettinger

Well, at the Selig film foundry they said Mr. Peters had just finished the retakes on Isobel, and was probably over at the Tourneur [Maurice Tourneur] works, whither he had been called to do The Great Redeemer, with little Marjorie Daw, loaned for the occasion by Marshall Neilan. At Universal City, where the Gaelic Maurice is leasing space for the nonce, I found the elusive Peters was “on location,” than which there could be nothing more vague. So for a few weeks I gave up my house hunting, and let the story ride.

The other day I learned that he was doing the male lead in Stewart Edward White’s Leopard Woman opposite Louise Glaum. Hopping a trolley for the rather remote regions known as Culver City — three studios and a drug store! — I knocked at the gates of the Ince studios, and had House Peters paged. An hour later found me on an African desert set, watching the object of my search prepare for a Sahara snooze, so to speak. Finally the Nubian slave [Noble Johnson] extinguished the candle lighting his tent interior, the baby spotlight threw a fitful moonbeam on the Peters face, his eyes closed in sleep, and the director yelled, “Cut!” Then I met House himself.

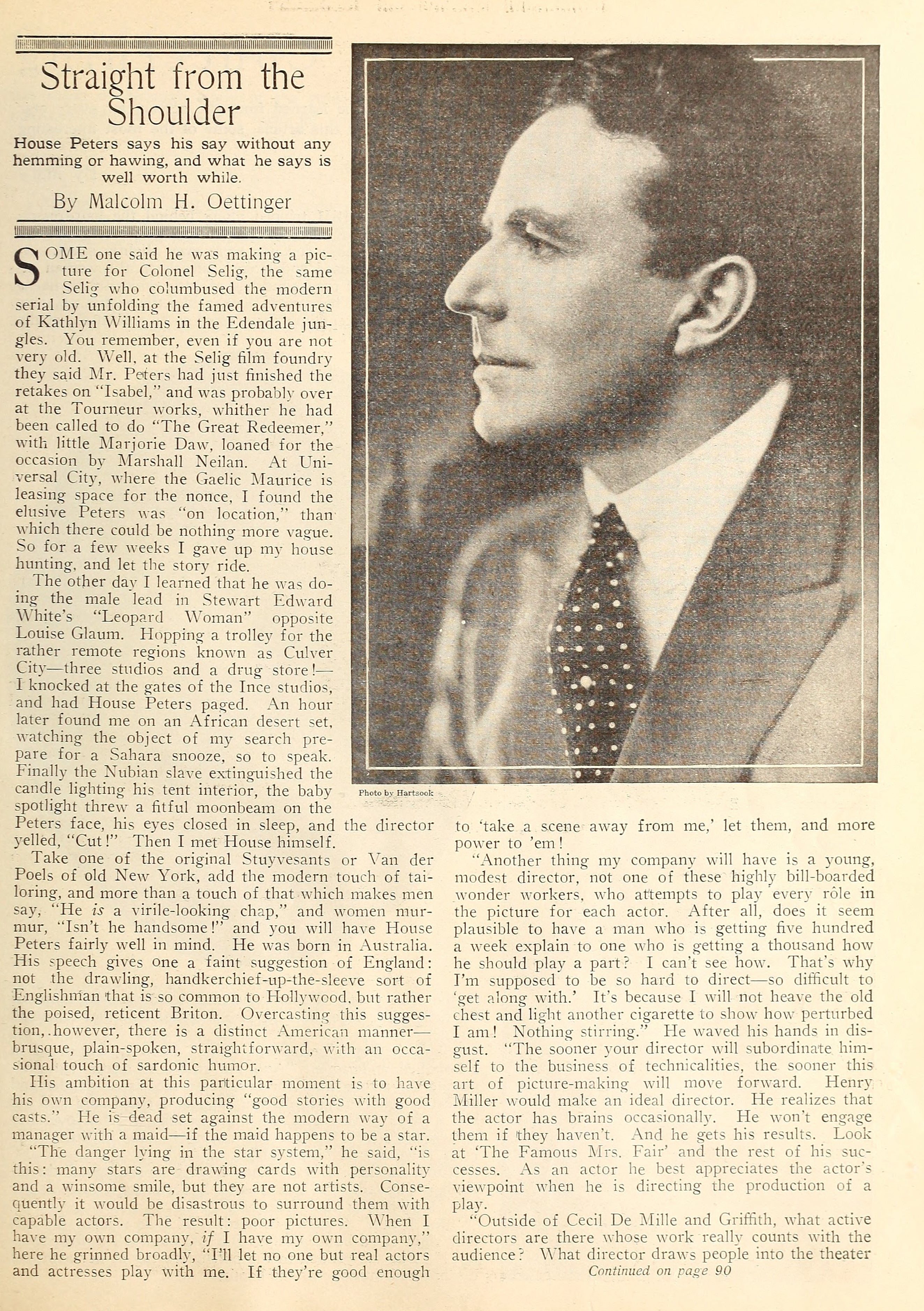

Take one of the original Stuyvesants or Van der Poels of old New York, add the modern touch of tailoring, and more than a touch of that which makes men say, “He is a virile-looking chap,” and women murmur, “Isn’t he handsome!” and you will have House Peters fairly well in mind. He was born in Australia. His speech gives one a faint suggestion of England: not the drawling, handkerchief-up-the-sleeve sort of Englishman that is so common to Hollywood, but rather the poised, reticent Briton. Overcasting this suggestion, however, there is a distinct American manner — brusque, plain-spoken, straightforward, with an occasional touch of sardonic humor.

His ambition at this particular moment is to have his own company, producing “good stories with good casts.” He is dead set against the modern way of a manager with a maid — if the maid happens to be a star.

“The danger lying in the star system,” he said, “is this: many stars are drawing cards with personality and a winsome smile, but they are not artists. Consequently it would be disastrous to surround them with capable actors. The result: poor pictures. When I have my own company, if I have my own company,” here he grinned broadly, “I’ll let no one but real actors and actresses play with me. If they’re good enough to ‘take a scene away from me,’ let them, and more power to ‘em!

“Another thing my company will have is a young, modest director, not one of these highly bill-boarded wonder workers, who attempts to play every role in the picture for each actor. After all, does it seem plausible to have a man who is getting five hundred a week explain to one who is getting a thousand how he should play a part? I can’t see how. That’s why I’m supposed to be so hard to direct — so difficult to ‘get along with.’ It’s because I will not heave the old chest and light another cigarette to show how perturbed I am! Nothing stirring.” He waved his hands in disgust. “The sooner your director will subordinate himself to the business of technicalities, the sooner this art of picture-making will move forward. Henry Miller would make an ideal director. He realizes that the actor has brains occasionally. He won’t engage them if they haven’t. And he gets his results. Look at ‘The Famous Mrs. Fair’ and the rest of his successes. As an actor he best appreciates the actor’s viewpoint when he is directing the production of a play.

“Outside of Cecil DeMille and Griffith [D. W. Griffith], what active directors are there whose work really counts with the audience? What director draws people into the theater by virtue of his own name, unaided by stars? I claim that the public wants to see Flossie Fewclothes or Bulwer Biffem, not how Morris Megaphone turned out the picture. Ask any fan what he or she goes to see, and list to the tale you will get. I appreciate the vast importance of good direction, but I maintain that the player remains the most important feature of the photo play. Of course, a good story is another essential. But without an efficient cast, neither DeMille nor D. W. himself could turn out big drama.”

For the past year, House Peters has deserted the gelatinous drama to attend to his business interests back in Australia. Previous to that he performed, in a celluloid way, for Famous Players, Triangle, Lubin, Brentwood, and Lasky.

“The first thing I ever did for the pictures was with Mary Pickford. In the Bishop’s Carriage was the play,” he said. “The best thing I have contributed was The Great Divide with Ethel Clayton, in which I believe I established something of a precedent by wearing a real beard. And what I would call my favorite role was the scrapping villain in Between Men, for Triangle. Don’t mention this Great Redeemer thing, though! That was — well, don’t see it!”

You will not find many actors advising you to stay away from their current exhibits. It was rather typical of the frankness and independence of the Peters temperament, however. He has a wife and a son and an automobile and a hunting dog and an amiable disposition. And after the Leopard Woman, he said, he has contracted to lend his screen appearance to a Thomas H. Ince special, from the Louis Joseph Vance novel, The Bronze Bell. Recent pictures are Isobel, the James Oliver Curwood story, in which he was supported notably by Jane Novak, and the already mentioned Tourneur opus, which, it is only fair to note, Maurice himself had no hand in directing.

But it is when House Peters has his own company that the fur will begin to fly.

Photo by: Hartsook

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, March 1921