Colleen Moore — Sometimes They Tell the Truth (1921) 🇺🇸

Tea with a motion-picture queen and not a thrill out of it!

by Celia Brynn

I suppose I should have been disappointed, but I wasn’t. A thrill-less interview is like a swim in a placid sun-kissed lake after having been buffeted about by roaring surf and mountainous waves. You enjoy the buffeting of surf-like temperament, the shock of tempestuous ideas, and the impact of egotism which you encounter when plunging into a cinema celebrity’s ocean of philosophy, but you feel supremely grateful for the quiet simplicity of a mind undisturbed by fame and riches; it is, after all, in the sun-kissed lake that you wish to loiter.

I knew, of course, before Colleen Moore invited me to tea that it wasn’t to be a “jazz” party. I knew that she wouldn’t consume a cigarette in a few greedy inhalations, or puff daintily at one — In fact, I knew that she didn’t smoke or drink — or even swear naively.

So, as I have said before, there was nothing thrilling about the interview. It was just a nice, comfy three-cornered chat, the third corner of the conversation being supplied by Elizabeth, Colleen’s debutante cousin from New Orleans.

You know how girls are when they get together.

There were questions about a diamond ring that Colleen wore and which she swore was a birthday gift from her father. Questions of the same sort about a ring which I wore and which I averred my mother had given me; and more pertinent queries about a frat pin that Elizabeth displayed conspicuously just below the deep collar of her linen frock.

Not much of an interview, you’re thinking. Well, it really wasn’t; although I did find out some things about this diminutive person that I hadn’t known before.

I discovered her real name, for instance. It had never occurred to me that she hadn’t been born with the name she has carried to screen success, but “Kathleen Morrison” is the way she was set down on the christening records just nineteen years ago.

“My grandmother, who is as Irish as a field of shamrocks, has always called me ‘Colleen,’ and every one else did, too, so it seemed more like me than the other. Mr. Griffith changed my name from ‘Morrison’ to ‘Moore,’ and the combination seemed to work so well that I have used it ever since.”

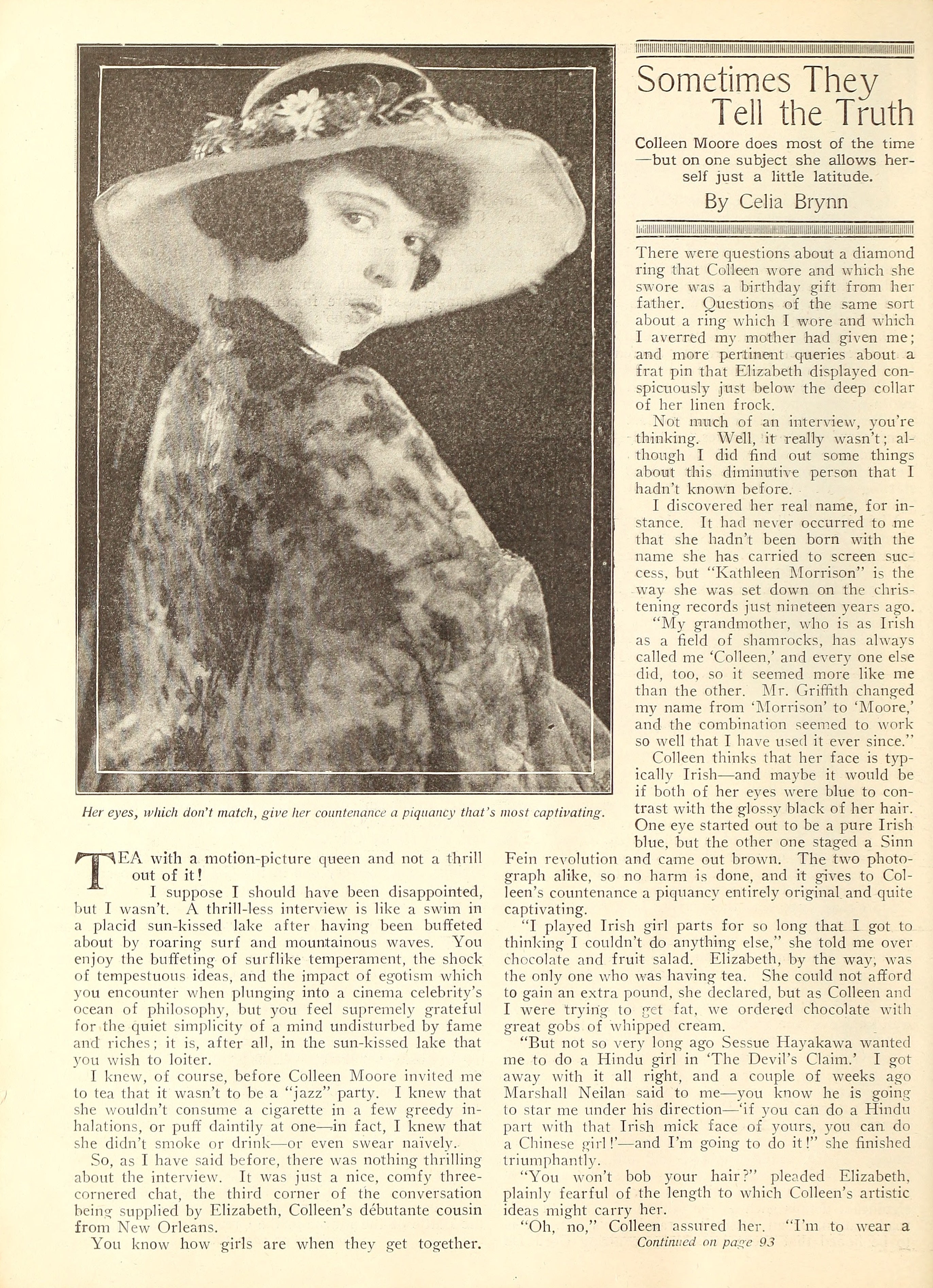

Colleen thinks that her face is typically Irish — and maybe it would be if both of her eyes were blue to contrast with the glossy black of her hair. One eye started out to be a pure Irish blue, but the other one staged a Sinn Fein revolution and came out brown. The two photograph alike, so no harm is done, and it gives to Colleen’s countenance a piquancy entirely original and quite captivating.

“I played Irish girl parts for so long that I got to thinking I couldn’t do anything else,” she told me over chocolate and fruit salad. Elizabeth, by the way, was the only one who was having tea. She could not afford to gain an extra pound, she declared, but as Colleen and I were trying to get fat, we ordered chocolate with great gobs of whipped cream.

“But not so very long ago Sessue Hayakawa wanted me to do a Hindu girl in The Devil’s Claim. I got away with it all right, and a couple of weeks ago Marshall Neilan said to me — you know he is going to star me under his direction — ‘if you can do a Hindu part with that Irish mick face of yours, you can do a Chinese girl!’ — and I’m going to do it!” she finished triumphantly.

“You won’t bob your hair?” pleaded Elizabeth, plainly fearful of the length to which Colleen’s artistic ideas might carry her.

“Oh, no,” Colleen assured her. “I’m to wear a bobbed wig and bangs. The working title is The Crimson Iris [Transcriber's Note: This might refer to The Lotus Eater (1921)] and I’m just crazy to start on it.”

“I should think you’d want a rest,” sighed Elizabeth, “after the years you’ve been working without even a week’s vacation.”

“What do you mean, ‘years’?” I cut in skeptically. “You talk as if she were a hoary veteran.”

“Well, I am kind of one,” defended Colleen. “I started in motion pictures four years ago — and that’s quite a while when you think of all the changes that have taken place in that time. I was going to school at a convent here in Los Angeles, but I was so anxious to make some money of my own that mother let me apply for work at the Griffith studio. I got it almost the first day and I worked there for over a year. I played my first part with Bobby Harron [Robert Harron]. Poor Bobby!” Her eyes filled suddenly with tears. “You can’t imagine what a wonderful boy he was, so — so good! I don’t believe he ever had a wrong thought in his life. Of course, I was just a youngster with my hair down my back and wearing flat-heeled shoes, and then Mr. Griffith gave me a part as a young lady — that was with Bobby, too — and I wore high heels for the first time.”

“And she wabbled!” declared Elizabeth with cousinly frankness. “I’ll never forget that picture. She’d wabble into a room on those ridiculous stilt heels, wabble out again, and once in a while look as if she was clutching something for support.”

Colleen giggled, a delicious subdéb giggle, and Elizabeth and I joined in. The waitress looked at us rather reprovingly. I think she had her ideas about the dignity of film stars.

“And then,” continued Colleen, starting in on a second cup of chocolate, “I made three comedies with Al Christie, Her Bridal Night-Mare, A Roman Scandal, and So Long Letty. The comedy experience was invaluable,” she assured me earnestly. “After I made those pictures, I was rented out. Yes, just like a horse or a typewriter. Of course, I didn’t mind, it was wonderful experience. I did some pictures for Selig, I played with Charlie Ray [Charles Ray] in The Egg Crate Wallop and worked in an all-star picture, When Dawn Came, then I did Dinty, for Marshall Neilan, with Wesley Barry as the leading man, and now” — she raised ecstatic eyes to the ceiling, “Mr. Neilan has given me a contract that’s perfectly wonderful! I think I’m the most fortunate girl in the world.”

The waitress presented a check, and the tip with which Colleen rewarded her restored, I am sure, her idea of what movie stars should be.

“But you haven’t asked me a thing,” said Colleen, aghast, as she drove me homeward in her new coupé, upholstered in elfin blue.

“You didn’t give her a chance to ask anything,” reminded Elizabeth.

“Well, there is something I’d like to know,” I remarked tentatively, as I stepped regretfully from the coupé’s luxurious interior to the prosaic cement pavement. “Where did you get that rig?”

“Oh — father —” Colleen commenced. And I appealed to Elizabeth.

“You see, they never tell you the truth when you do ask them questions,” I said aggrievedly.

“Well, father did give it to me!” she maintained with an emphasis entirely unnecessary.

And maybe he did, but as I said confidentially to Elizabeth, I have my own ideas about it.

Her eyes, which don’t match, give her countenance a piquancy that’s most captivating

From a Director’s Dictionary

- Curled Mustaches — Denoting a villain.

- Wavey Hair — Denoting a hero.

- Wide Eyes — Denoting a heroine.

- Black Eyes — Denoting a vamp.

- The Theater — A place always inhabited by stage-door Johnnies and gentlemen with villainous designs on the leading lady.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, March 1921