Evelyn Brent — As She Is (1929) 🇺🇸

She has common sense, but not enough to be calculating. She has sanity, but not enough to be dull. She has determination, but not enough to be arrogant. She is regular, but not average; normal, but not prosaic.

by Margaret Reid

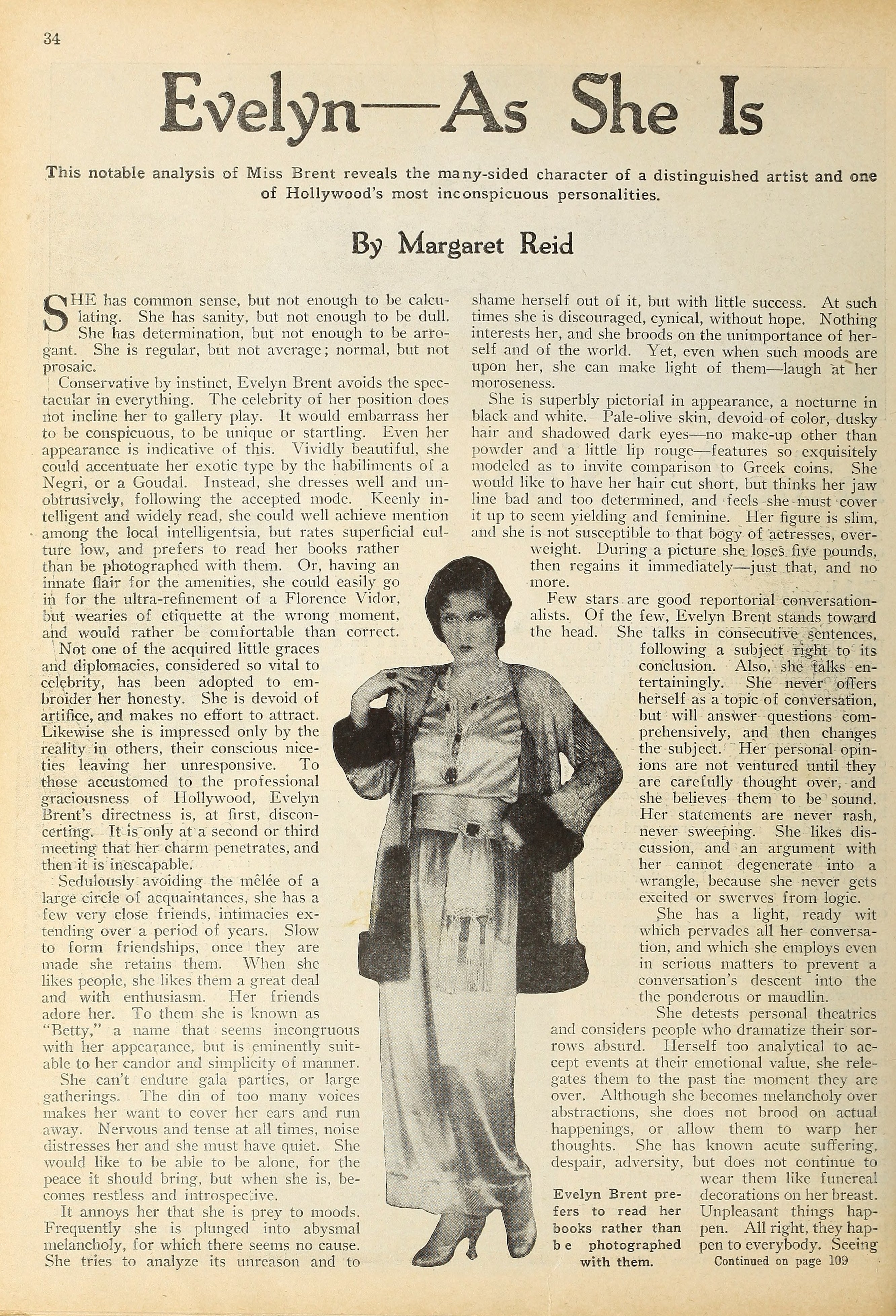

Conservative by instinct, Evelyn Brent avoids the spectacular in everything. The celebrity of her position does not incline her to gallery play. It would embarrass her to be conspicuous, to be unique or startling. Even her appearance is indicative of this. Vividly beautiful, she could accentuate her exotic type by the habiliments of a Negri [Pola Negri], or a Goudal [Jetta Goudal]. Instead, she dresses well and unobtrusively, following the accepted mode. Keenly intelligent and widely read, she could well achieve mention among the local intelligentsia, but rates superficial culture low, and prefers to read her books rather than be photographed with them. Or, having an innate flair for the amenities, she could easily go in for the ultra-refinement of a Florence Vidor, but wearies of etiquette at the wrong moment, and would rather be comfortable than correct.

Not one of the acquired little graces arid diplomacies, considered so vital to celebrity, has been adopted to embroider her honesty. She is devoid of artifice, and makes no effort to attract. Likewise she is impressed only by the reality in others, their conscious niceties leaving her unresponsive. To those accustomed to the professional graciousness of Hollywood, Evelyn Brent’s directness is, at first, disconcerting. It is only at a second or third meeting that her charm penetrates, and then it is inescapable.

Sedulously avoiding the melee of a large circle of acquaintances, she has a few very close friends, intimacies extending over a period of years. Slow to form friendships, once they are made she retains them. When she likes people, she likes them a great deal and with enthusiasm. Her friends adore her. To them she is known as “Betty,” a name that seems with her appearance, but is eminently suitable to her candor and simplicity of manner.

She can’t endure gala parties, or large gatherings. The din of too many voices makes her want to cover her ears and run away. Nervous and tense at all times, noise distresses her and she must have quiet. She would like to be able to be alone, for the peace it should bring, but when she is, becomes restless and introspective.

It annoys her that she is prey to moods. Frequently she is plunged into abysmal melancholy, for which there seems no cause. She tries to analyze its unreason and to shame herself out of it, but with little success. At such times she is discouraged, cynical, without hope. Nothing interests her, and she broods on the unimportance of herself and of the world. Yet, even when such moods are upon her, she can make light of them — laugh at her moroseness.

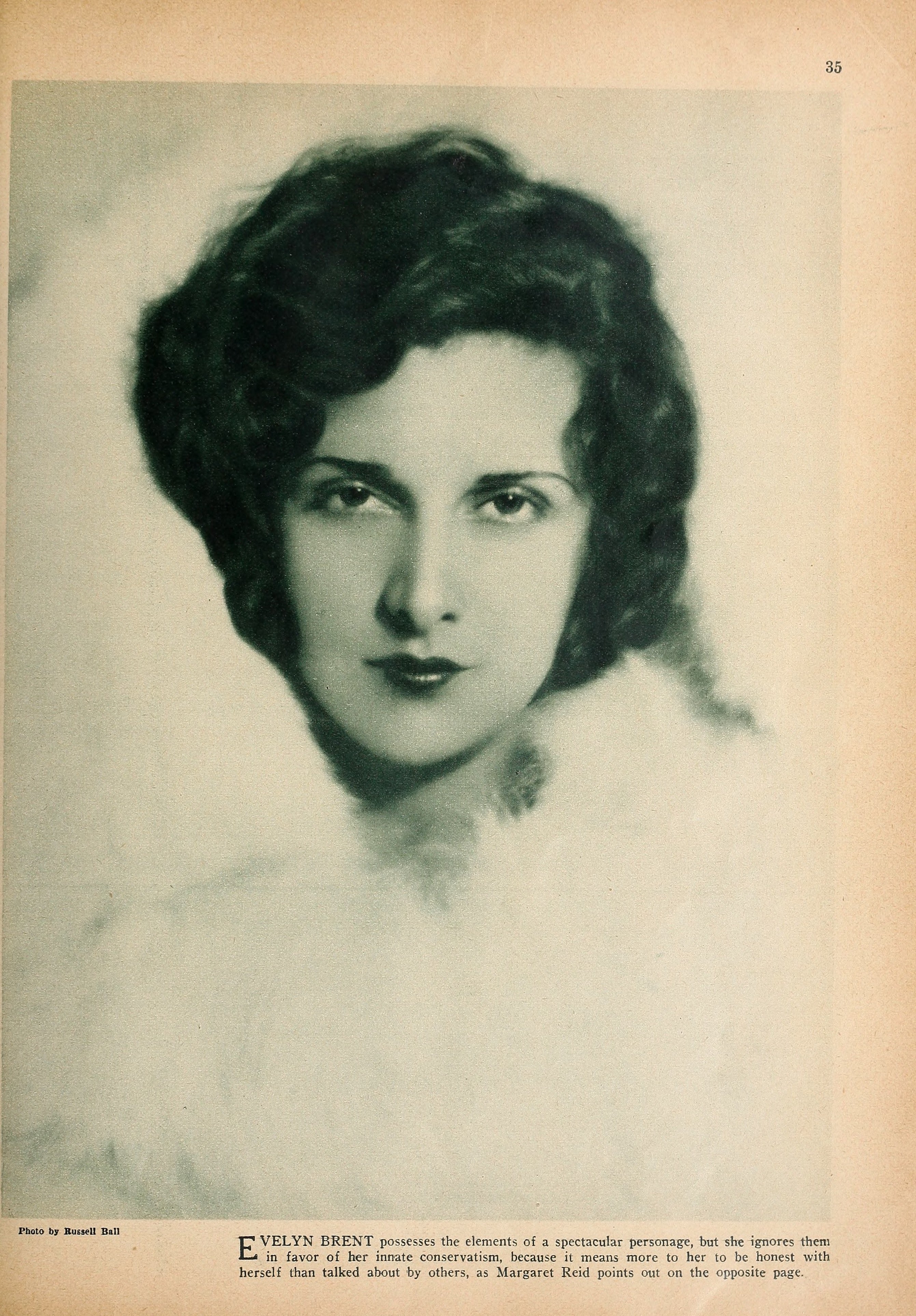

She is superbly pictorial in appearance, a nocturne in black and white. Pale-olive skin, devoid of color, dusky hair and shadowed dark eyes — no make-up other than powder and a little lip rouge — features so exquisitely modeled as to invite comparison to Greek coins. She would like to have her hair cut short, but thinks her jaw line bad and too determined, and feels she must cover it up to seem yielding and feminine. Her figure is slim, and she is not susceptible to that bogy of actresses, overweight. During a picture she loses, five pounds, then regains it immediately — just that, and no more.

Few stars are good reportorial conversationalists. Of the few, Evelyn Brent stands toward the head. She talks in consecutive sentences, following a subject right to its conclusion. Also, she talks entertainingly. She never offers herself as a topic of conversation, but will answer questions comprehensively, and then changes the subject. Her personal opinions are not ventured until they are carefully thought over, and she believes them to be sound. Her statements are never rash, never sweeping. She likes discussion, and an argument with her cannot degenerate into a wrangle, because she never gets excited or swerves from logic.

She has a light, ready wit which pervades all her conversation, and which she employs even in serious matters to prevent a conversation’s descent into the the ponderous or maudlin.

She detests personal theatrics and considers people who dramatize their sorrows absurd. Herself too analytical to accept events at their emotional value, she relegates them to the past the moment they are over. Although she becomes melancholy over abstractions, she does not brood on actual happenings, or allow them to warp her thoughts. She has known acute suffering, despair, adversity, but does not continue to wear them like funereal decorations on her breast. Unpleasant things happen. All right, they happen to everybody. Seeing no reason why she should he exempt, she does not feel martyred. Sympathetic and understanding of the troubles of others, she seldom refers to her own and, when she does, it is humorously.

On one occasion, she did inadvertently speak of a dismal period during her early days on the stage. The occasion was an interview and, although Evelyn did not dilate on the dramatic aspects of the event, the interview was published as a minor tragedy. For weeks after it came out, she was in a torment of embarrassment, fearful that her friends had seen it. Since then she has been cautious in her statements to the press. This type of publicity, together with the recent inundation of “love-life confessions,” she considers the height of bad taste, and believes that the public can only be offended by the vulgarity, and amused by the inanity, of it.

She loves the stage and deplores the scarcity of good entertainment in the Los Angeles theater. Well-executed plays are a source of keen delight to her, and she would like to have more time for vacations in New York. Hoping, some day, to return to the stage, she welcomes talking pictures, and the consequent use of intelligent plays for screen material. Her first talkie was Interference, adapted with care from the stage production. She was nervous of the microphone, grateful that any sound at all emerged from her mouth when she opened it, and is prepared for the worst when she sees the picture. Not habitually a victim of stage fright, however, she looks forward to the next one as a probable improvement. Her voice should register excellently, being low pitched and full. She is fascinated by the making of talking pictures and tries to understand the process, but is lost in the intricate technicalities.

Until “Underworld” she was not particularly interested in her career. Apparently doomed to mediocre pictures, work was incidental, something that had to be done and gotten out of the way.

When Underworld was released, Evelyn Brent was rediscovered by the fans and discovered by the critics. There followed a contract with Paramount and intelligent roles in good pictures. Her interest awakened, Evelyn began to give her work more attention, tried to be less amenable to suggestion, and to object when attempts were made to force her into unsuitable parts.

Loathing any role smacking of the ingenue, and having proved to her own satisfaction that she is terrible in that type, she holds out bravely for more adult forms of entertainment. She wishes there were more demand for stories dealing with mature people, men and women of middle age who are experienced, mellow, and wise. There, she thinks, lies real drama, and cites Pauline Frederick as one of its successful exponents. Emil Jannings is another of her favorites, and she thinks Greta Garbo eye-filling, breath-taking, amazing.

At times Evelyn wonders why she is in pictures, why she continues — it seems to her silly and unsatisfactory. Yet an urge drives her to do something. Acting is the only thing she knows and, despite these misgivings, she likes it. Not satisfied with this, she must find out why she likes it, and it is when she can’t decide that she feels its futility. It is probably the basis of her moods, this self-analysis and passion for having no delusions about herself.

Recently divorced from B. P. Fineman, the Paramount executive to whom she had been married over four years, she finds herself jarred, and readjustment necessary. Although the separation was accompanied by no rancor, and they are still friends, she admits the difficulty of change. Creatures of habit, and made to live neither alone nor with any one, she thinks that the fault lies less with the institution of marriage, than with the construction of humans. Before, and if, she marries again she will have to be sure of a mutual tolerance, the quality she considers most necessary, and almost impossible to combine with love.

A driving restlessness being dominant in her, it is surprising that she has stayed six years in Hollywood. She loves to travel, would like always to be free to pick up and leave on every impulse. Partial to Europe, she would prefer, if forced to select a permanent abode, to live in London.

She lives now in a spacious, imposing house set atop terraced lawns on a quiet street between Hollywood and Beverly Hills. She took the place principally for the wide gardens around it, and the stillness of the neighborhood. It is furnished throughout in the modern manner, which she adores. She wants to build a house in the modern architecture now being experimented with in Europe.

Her library is filled with cases that overflow with books — books not bought for decoration, but for practical purposes. First editions, special editions, rare printings, signed copies, all exemplifying understanding and discrimination. She likes biography, Samuel Hoffenstein’s Poems in Praise of Practically Nothing, Lester Cohen’s play Oscar Wilde, and almost anything intelligently conceived and well done. Her abomination is the best-seller book, and her despair the fact that if she chances upon one by mistake, she reads it through, optimistic to the end, and is then roused to disgust and anger.

She would like to understand music, that she might enjoy it without being conscious of missing its real import, but has never had the opportunity. She admits to this without pretense, unaware that she might just as easily sigh, “Ah, Beethoven!” and be put down as a connoisseur. This candor is one of her most ingratiating traits, making a paradox of her sophistication.

She is an arresting person, a vitally charming one, and herself — Evelyn Brent — without compromise or embellishment.

[Editor’s Note. — Since this was written Miss Brent married Harry Edwards, a director.]

Evelyn Brent prefers to read her books rather than be photographed with them.

Evelyn Brent possesses the elements of a spectacular personage, but she ignores them in favor of her innate conservatism, because it means more to her to be honest with herself than talked about by others, as Margaret Reid points out on the opposite page.

Photo by: Russell Ball (1891–1942)

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, February 1929