Adolphe Menjou — As He Is (1929) 🇺🇸

He is the one box-office star who has steadily made really good pictures. He has more well-executed and intelligent program pictures to his credit than almost any other luminary in the business. Without being dolefully Russian in feeling, Menjou productions are food for adults. His comedies offer no belly laughs, but are designed to amuse and satisfy the more intelligent audiences. Despite which, they consistently make money.

by Margaret Reid

He knows, and willingly admits, that he has several good pictures to his credit, but does not delude himself into thinking they are great pictures. He thinks that great pictures occur on an average of once every couple of years, and then only accidentally. He scoffs at the notion of movies being rated an art. They are, he says, a mechanical contrivance, a fine business for the financially ambitious.

Menjou is distressed when he finds he has made a bad picture, and alludes to it quite as frankly as he does to a good one. He is guilty of neither false modesty nor undue self-satisfaction. He views himself with unprejudiced clarity, and similarly does he view his friends and contemporaries. He often wounds tender Hollywood vanities by his candid criticism, and when he discovers this, is impatient rather than regretful. When, on the other hand, criticism is offered him, he receives it with interest.

He has an extraordinarily quick mind, and expresses himself rapidly and concisely. His opinions are more radical than otherwise, and tenaciously retained in an argument, but presented with disconcerting logic. It is difficult for slower minds to keep pace with his swift trains of thought. Like all people who are mentally a jump ahead of others, he is inclined to be irritated by this seeming sluggishness, but never allows his impatience to become chronic.

His nervous energy is unflagging. It is this with which he generates his company so that Menjou pictures are turned out, polished and meticulously detailed, in a schedule usually identified with quickies — twenty days being his average shooting time. In spite of this production speed, every Menjou film is more carefully done than many which are two months in the making.

Menjou is conscious of the limitations of his appeal, claiming that, since he is not handsome, romantic, or juvenile, he depends on stories for success. Preferring light comedy-drama, he tries always to appear in stories of definite charm and sophistication.

The studio gives him power of veto on stories, and of selection of cast and director. He likes new blood in his troupe and considers it worth his while to take a chance on promising newcomers, because of their pristine enthusiasm. Discovery by Menjou has catapulted more than a few players and directors to success.

Discerning and intelligent, he deplores the impossibility of making better general use of moving pictures as a medium, but admits that the impossibility is an economic fact. He has schooled himself to accept conditions as they are and to do the best he can under difficult circumstances, such as ignorant supervision, moronic public demand, and the confusion of studio politics. He is an ardent disciple of talking pictures, and has just finished his first, The Concert.

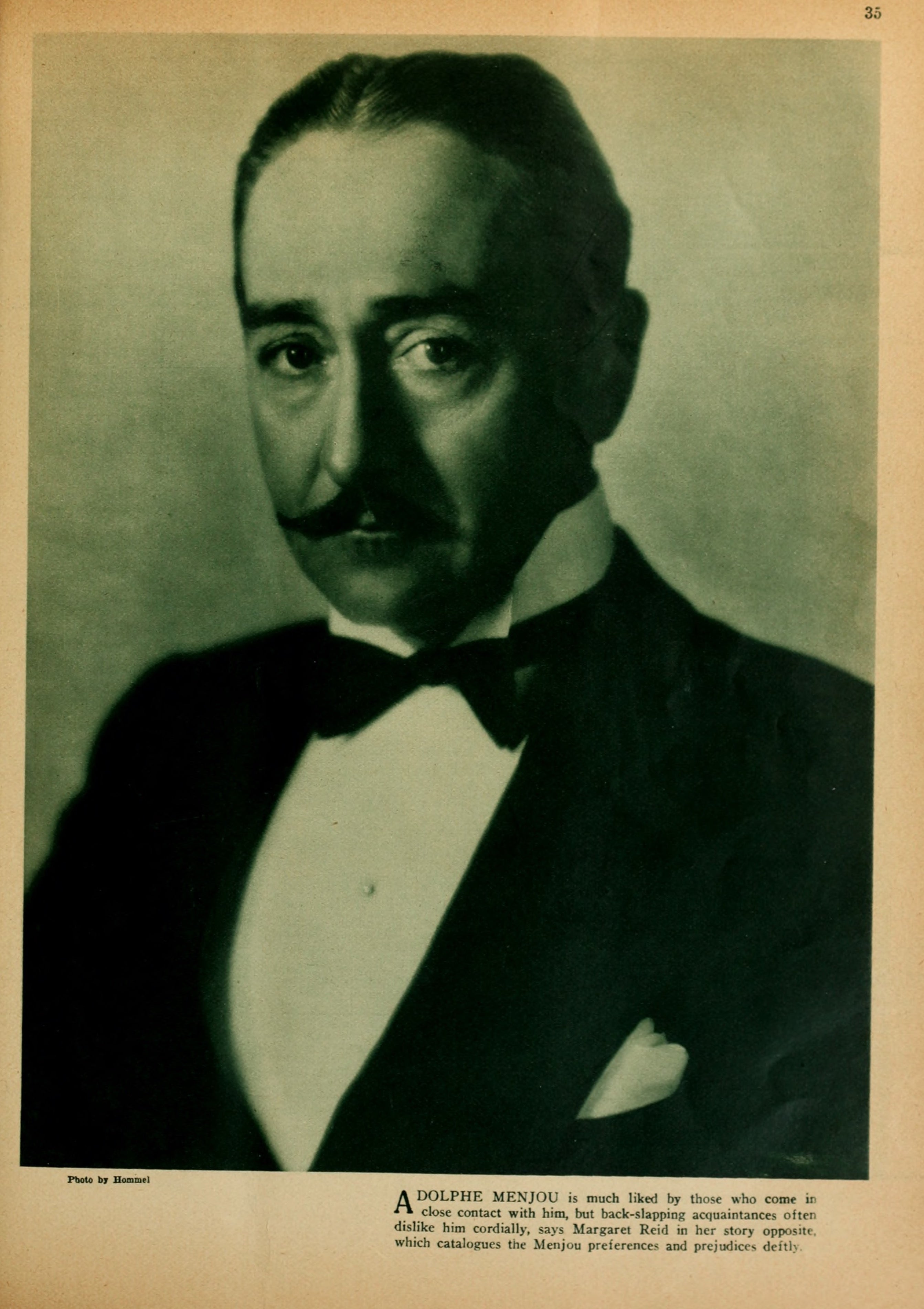

By those who come into close contact with Menjou, he is tremendously well liked. By casual acquaintances, who do not understand him, he is often disliked. Amiable and friendly, yet he is not a back-slapper. In Hollywood, where a point has to be got over with a hammer, his affability is not insistent enough to prove itself to the professional democrats of the Boulevard. He knows this, but does not exert himself to swing popular opinion in his favor, finding it not of sufficient importance. He does not keep open house, as is the custom in Hollywood. It does not amuse him to entertain large gatherings of comparative strangers who would use his home for a stamping ground. Nor does he make a practice of attending big parties. When he has been inveigled into going, he spends a miserable evening, leaving as early as is civil. He and his wife have a small circle of intimates, and he is happiest when confining his social contacts to this circle.

Mrs. Menjou is Kathryn Carver — blond, beautiful and a tranquil balance for his more excitable temperament. After being a charming foil in several of his pictures, she has retired more or less permanently from the screen. His chief aversion is ostentation in anything. Included is a distaste for those Hollywood manses patterned after the Grand Central Station. His own house in the Los Feliz hills is relatively small, ten or twelve moderately sized rooms, compactly arranged. It is a little gem of taste and discrimination, furnished throughout with objects chosen by Menjou himself for their correctness and authenticity.

Contrary to the expectation that the suave gentleman of Paris might fancy Borzois, he has an extensive kennel of prize Aberdeen terriers. And in the house are two large and raucous parrots, to whom he is devoted.

He is given to enthusiasms which consume all his interest for the length of their duration. Innately serious, he is carried away by the possibility of a new discovery and concentrates all his thought on it. A short time ago it was Russian literature. He precipitately decided that here were the Elysian fields of writing. To fit himself to full appreciation of it he began a comprehensive study of the country itself, the people, political conditions and history, and had an instructor on the set every day to teach him the language between scenes.

An accomplished linguist, Menjou speaks French, German, Spanish, Italian, and Russian fluently. With the advent of talking pictures, he will probably turn this to practical advantage. He is convinced that the foreign-market difficulty confronting the talkies will be solved by the big organizations establishing branch studios abroad. He hopes to do a foreign talkie on his next trip to Europe.

He dislikes California as a place to live, and would prefer to reside in New York and spend two or three months of the year in Hollywood. He likes to take an annual trip abroad, having a dread of the mental torpor which afflicts residents of the film colony who are content with vacations at Santa Monica.

The public appearance of Adolphe Menjou is a thrill of which all but the most observant fans are deprived, his presence along the highways seldom being suspected. Because it makes him uncomfortable to be pointed at, as if he were a choice zoological treasure, he defends himself against recognition by wearing smoked glasses and assiduously chewing gum.

Although his pictures have a leisurely, suave tempo, Menjou himself is brisk and forthright in manner. Unlike his cinema personality, he is given to candor rather than innuendo, to simplicity rather than subtlety. Inherently of a nervous disposition, he is restless and finds extreme satisfaction in travel, movement, new vistas.

It is his contention that the business of living has come to be neglected and, particularly in Hollywood, is it a lost art. In two or three years Menjou will have accumulated enough money to satisfy his ambition, and he plans to retire then. He will devote his energy to savoring life at his leisure, and with the complete appreciation impossible when there are the demands of business to be considered. And, being Adolphe Menjou, he will be a success at it.

—

Mr Menjou’s ability to work rapidly, yet carefully, has resulted in a long list of well-executed pictures.

—

—

Adolphe Menjou is much liked by those who come in close contact with him, but back-slapping acquaintances often dislike him cordially, says Margaret Reid in her story opposite, which catalogues the Menjou preferences and prejudices deftly.

Photo by: Hommel

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, August 1929