Gregory la Cava — Stars Shot from Ink Pots (1918) 🇺🇸

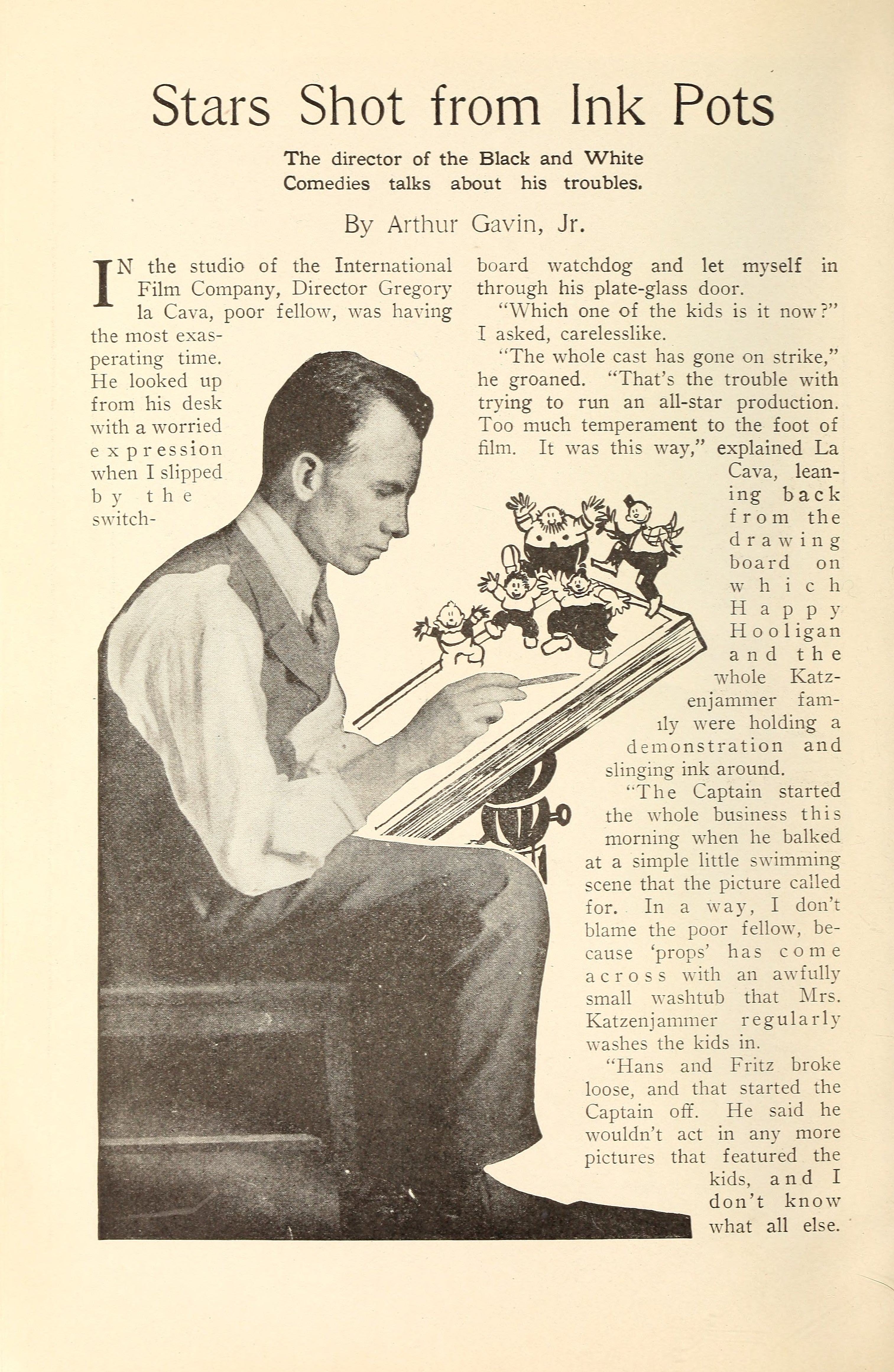

In the studio of the International Film Company, Director Gregory la Cava, poor fellow, was having the most exasperating time. He looked up from his desk with a worried expression when I slipped by the switchboard watchdog and let myself in through his plate-glass door.

by Arthur Gavin, Jr.

“Which one of the kids is it now?” I asked, carelesslike.

“The whole cast has gone on strike,” he groaned. “That’s the trouble with trying to run an all-star production. Too much temperament to the foot of film. It was this way,” explained la Cava, leaning back from the drawing board on which Happy Hooligan and the whole Katzenjammer family were holding a demonstration and slinging ink around.

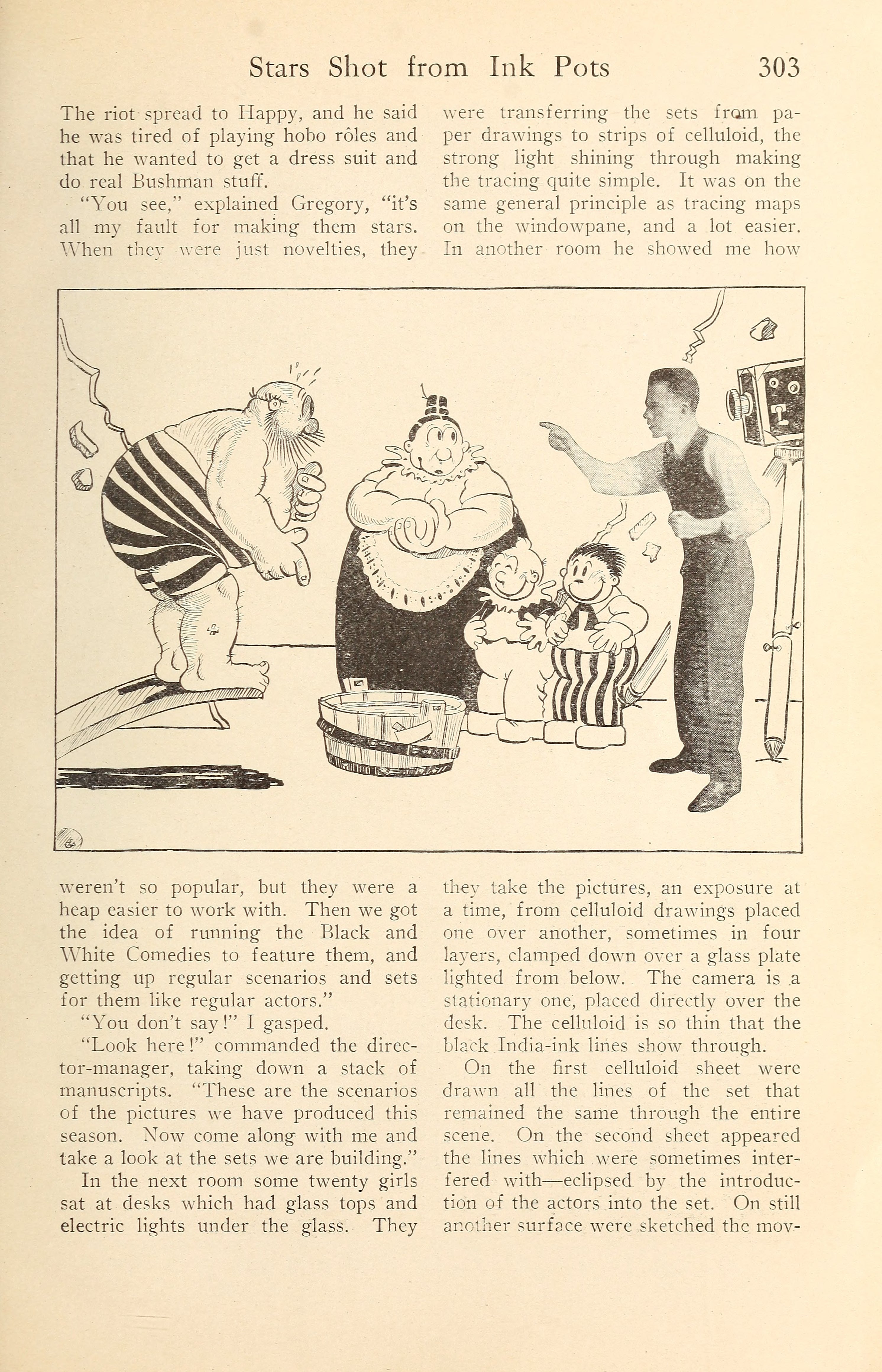

“The Captain started the whole business this morning when he balked at a simple little swimming scene that the picture called for. In a way, I don’t blame the poor fellow, because ‘props’ has come across with an awfully small washtub that Mrs. Katzenjammer regularly washes the kids in.

Hans and Fritz broke loose, and that started the Captain off. He said he wouldn’t act in any more pictures that featured the kids, and I don’t know what all else.

The riot spread to Happy, and he said he was tired of playing hobo roles and that he wanted to get a dress suit and do real Bushman [Francis X. Bushman] stuff.

“You see,’’ explained Gregory, “it’s all my fault for making them stars. When they were just novelties, they weren’t so popular, but they were a heap easier to work with. Then we got the idea of running the Black and White Comedies to feature them, and getting up regular scenarios and sets for them like regular actors.”

“You don’t say!” I gasped.

“Look here!” commanded the director-manager, taking down a stack of manuscripts. “These are the scenarios of the pictures we have produced this season. Now come along with me and take a look at the sets we are building.”

In the next room some twenty girls sat at desks which had glass tops and electric lights under the glass. They were transferring the sets from paper drawings to strips of celluloid, the strong light shining through making the tracing quite simple. It was on the same general principle as tracing maps on the windowpane, and a lot easier. In another room he showed me how they take the pictures, an exposure at a time, from celluloid drawings placed one over another, sometimes in four layers, clamped down over a glass plate lighted from below. The camera is a stationary one, placed directly over the desk. The celluloid is so thin that the black India-ink lines show through.

On the first celluloid sheet were drawn all the lines of the set that remained the same through the entire scene. On the second sheet appeared the lines which were sometimes interfered with — eclipsed by the introduction of the actors into the set. On still another surface were sketched the movable objects, such as the table, chairs, and bathtub, together with those parts of the actors which remained still through a number of exposures — their bodies and legs in one case, for instance, while their heads, faces, and hands did the action. On the fourth sheet, which was the paper, appeared the moving objects; for example, the Captain’s fist, moving up and down, each single movement being depicted by a series of several different exposures.

“It’s a great little system, if you don’t weaken,” I commented; “but I should think it would take a month to make one of those comedies.”

“It would take even longer,” he replied, “if one man tried to do it alone. We have a force of nearly thirty artists and tracers here, working full time on these comedies alone, and we manage to produce a comedy a week. That is,” he amended, “not allowing for time lost by a stupid ‘props’ or the temperament of the actor.”

“Some little excursion, Gregory, and the next time I see one of these comics on the screen I’ll remember how you do it. S’long, and I hope the stars will come to terms.”

“Oh, they will,” said their director. “And there’s one thing I don’t have to worry about: The whole cast is under contract for the rest of their natural lives.”

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, August 1918

—

see also