William Haines — The Young Man of the Hour (1928) 🇺🇸

The young man of the hour is William Haines. You probably knew it all the time. To any one who has been following the fortunes of the film people, it has become increasingly apparent that the ingratiating Haines is the logical choice for president this year. His performances have been pyramiding prodigiously: hit has followed hit, triumph has topped triumph. It is a Haines year.

by Malcolm H. Oettinger

The screen never has been exactly top-heavy with acceptable juveniles, as they are called. Once upon a time there was Jack Pickford. Dick Barthelmess [Richard Barthelmess] came and went, returning in The Patent Leather Kid. The recent boys, Don Alvarado and Richard Arlen and Gilbert Roland and the rest, are pretty much of a pattern, cut from the same celluloid. Young Fairbanks [Douglas Fairbanks Jr.] may possibly be developed, and Buster Collier has his bright moments, but the field, as viewed through these binoculars, is clear for Haines. His nearest rival is Charles Farrell, who will be considered at a future date.

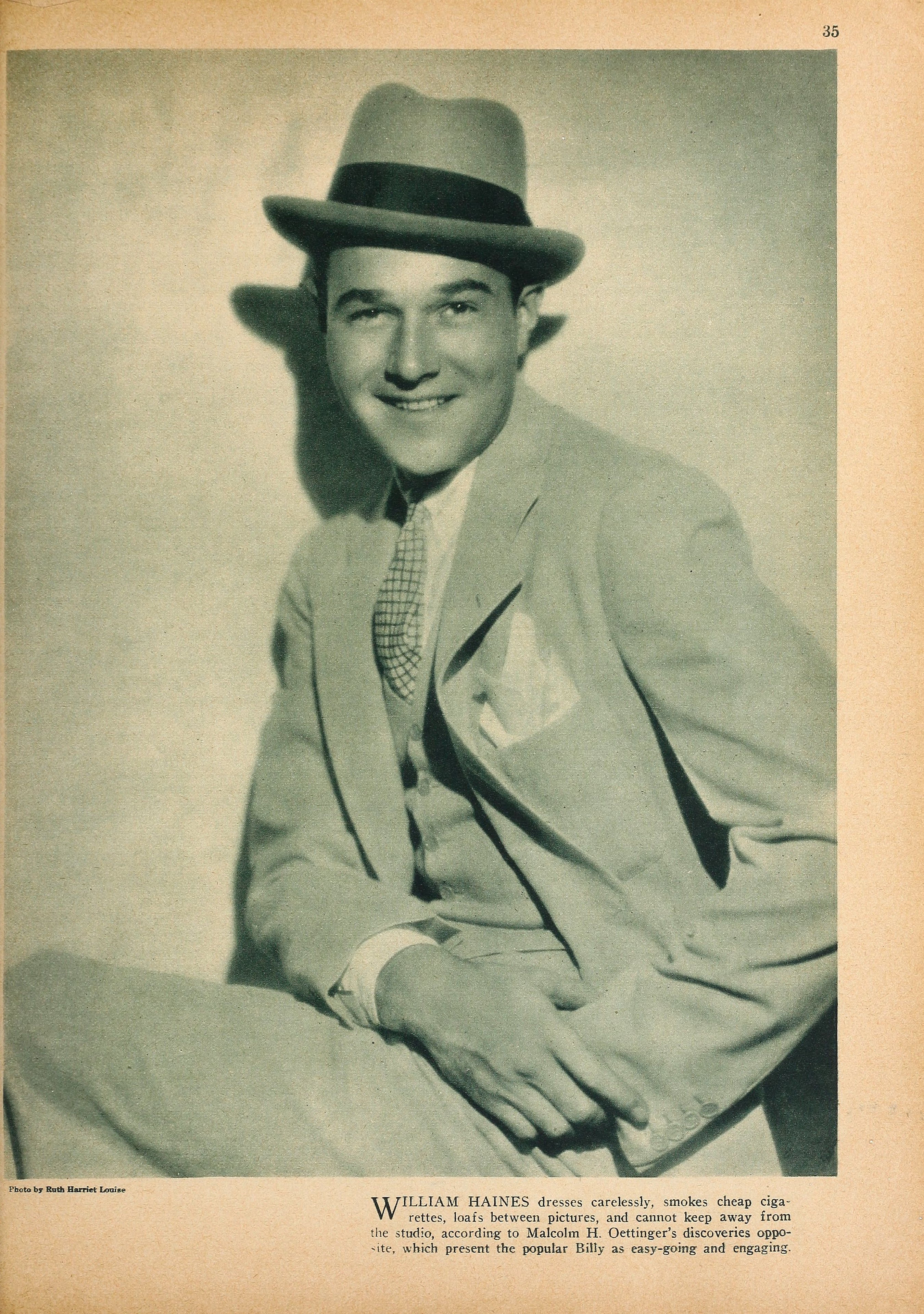

Haines is neither too handsome nor too noble in his screen incarnations; he is upstanding in an inoffensive way. Away from the camera he is a brash, easy-going youth with a world of confidence and an abundant personality.

He was wandering about the vast expanses presided over by Metro and Goldwyn and Mayer, and he preferred sight-seeing to being interviewed. Clad in a collegiate sweater and equally collegiate flannels, he visited set after set, helloing and hey-heying as he went. He stopped to hear Polly Moran’s latest story, consulted Greta Garbo about duck hunting, paused to wish Dorothy Sebastian luck on her new picture, and borrowed a cigarette from Eddie Brophy, an assistant director.

Haines is good looking in a boyish, healthy way. His smile is worth thousands at any box office. He talks boyishly, too, relying upon an easy, natural manner to ingratiate himself. As a matter of fact, he is riding along on personality, and it will carry him far. Personality counts far more in filmdom than either looks or ability. Personality, definitively speaking, is the open sesame to success, bulky pay envelopes, imported, cars with special bodies, and national popularity.

“Nothing but blue skies,” he quoted blithely, as we strolled along. “I always say that California climate is just about the swellest climate in California. Always sunnyside up. Except in January, August, and two to grow on.”

The carefree manner was super-induced by the fact that not long since, Bill had been presented with a new contract that tilted his weekly check at approximately a forty-five-degree angle.

For four years he was a stock actor at Metro, three years playing bits that were infinitesimal. “Usually I was the flash of lightning, or the shriek in the dark,” Bill explains. Then opportunity knocked, and Haines was on his toes as he fairly jumped at the chance.

Haines came to Hollywood without having so much as carried a spear in support of Robert B. Mantell; indeed, he had never been on the stage at all. True, there were amateur theatricals at Staunton Military Academy, but any casting director would regard that as a liability rather than an asset.

Bill went to Staunton because he is a native of Staunton, Virginia. Continuing in biographical strain, it is perhaps not irrelevant to note that he is twenty-eight, unmarried, black-haired, lazy, good-natured and fond of reading in bed.

Joseph Conrad and Donald Ogden Stewart are his favorite authors, sufficiently diversified to suit any one, and the car made famous by Michael Arlen is his favorite, too. He is saving up for one.

“Can’t you see me riding down Santa Monica Boulevard, with my long, white beard flying proudly in the breeze?” Bill asked. “It will be the proudest day of my life.”

When he heard that John Robertson [John S. Robertson] had cajoled the front office into producing Joseph Conrad’s Romance — called, in the films, “The Road to Romance” — he was all for doing the young adventurer, but Robertson elected Ramon Novarro: “I don’t want to get single-parted,” Bill said. “I like comedy, of course, but I want to do all kinds of pictures. So far, I’ve done fresh young fellas. The wise-guy type is ‘oke’ if you don’t overplay him. But you know how the public is. It wants a change of pace every so often, if not oftener. That’s my yen. To give ‘em variety and plenty of it. Baseball, golf, West Point — fine. But different bozos, too, don’t you think?”

As you may gather from this untrammeled report, Bill is a good egg, normal in his enthusiasm, his hopes,

his ambitions, and his ego. He is growing into his mounting wave of popularity gracefully. He has one runabout, one bungalow — which he shares with his mother — and one dog. He dresses carelessly, smokes cheap cigarettes, loafs prodigiously between pictures, and cannot keep away from the studio.

“Nothing interests me as much as pictures,” he says, “so why shouldn’t I put in my spare time here? I get a kick out of it.”

From the military academy in the home town, Bill went to New York, and decided that an up-and-doing young man should be selling something, probably bonds to wealthy bankers with distinguished goatees. He saw himself accepting certified checks in the morning, lunching at the Union League, and devoting his afternoon to golf.

“It all worked out perfectly,” said Bill, “except that I didn’t sell any bonds in the morning, I ate at one-armed, feed-yourself joints, and afternoons I spent looking for better-paying jobs, or jobs that paid anything. But they were practically invisible.”

According to legend, he was noticed in the midday crowd in Wall Street by an emissary of Samuel Goldwyn — a lady — who was captivated by Bill’s lazy stride. He was, in the course of preliminaries, sent to California at seventy-five dollars a week.

If you think this is one of those success stories, stop me. The Haines advance was little more than a crawl. Progress was so slow that he thought that he was standing still. He happened to be given extra work now and then, and he ate regularly, so he was encouraged to stay.

Out at Culver City he made a couple of appearances in succession under Goldwyn auspices. Some one took another test of him and was mildly impressed, though at first he had been handicapped by lack of sex appeal. All this took many months to transpire. At the end of a year, Bill found himself still on the Coast, with a job that at least paid steadily, and vague prospects of advancement. That was in 1922. The chance for which he was literally holding his breath didn’t materialize until 1926.

In the meantime he had to heed, hang on, and hope. He had to display patience, pluck, perseverance, and other things highly touted by Doctor Frank Crane, Gene Tunney, and President Lowell. He had to believe in himself. Personality fades with pessimism. The Haines smile had to be on exhibit at all times. Then somebody saw it one day, and suggested him for Brown of Harvard, and the rest was comparatively easy.

“That picture was a break in a million,” Bill says. “I was so happy when I heard that I was to do it, I went around for days singing ‘Fair Harvard’! You know how pictures are. One break is apt to follow another. I had mine in Brown. They gave me Tell It to the Marines next. Then they capped things with ‘Slide, Kelly,’ a swell story with a swell guy directing. It’s fun working with Eddie Sedgwick [Edward Sedgwick]. All the laughs in the calendar. We kid and clown, then all of a sudden he’ll say, ‘Let’s take it,’ and we do. And there it is. He works fast, and he has a great bean.”

Following the golf comedy called “Spring Fever,” they did West Point. Joan Crawford lent sex voltage to both pictures.

“She’s a great girl,” admitted Bill. “Another lucky angle for me. I’m beginning to believe in Santa Claus, Will Plays, and National Smile Week. Everything is hotsy-totsy, and, “I’ll put that in writing.”

All that Haines needed to hit his natural stride was a chance. He got it and he hit it. To-day there is no one swinging along quite so briskly, quite so jauntily, quite so assuredly.

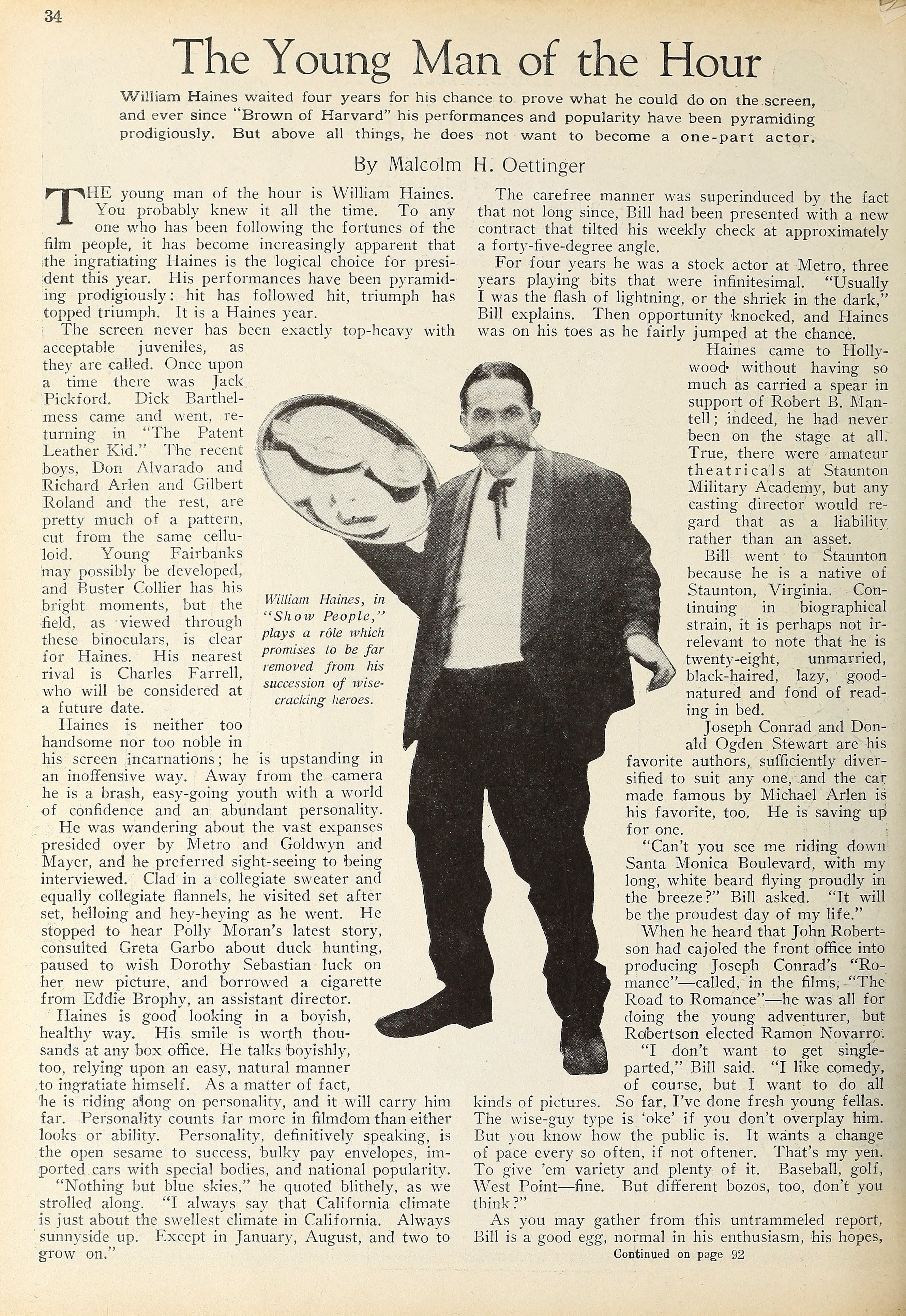

William Haines, in “Show People,” plays a role which promises to be far removed from his succession of wisecracking heroes.

William Haines dresses carelessly, smokes cheap cigarettes, loafs between pictures, and cannot keep away from the studio, according to Malcolm H. Oettinger’s discoveries oppose, which present the popular Billy as easy-going and engaging.

Photo by: Ruth Harriet Louise (1903–1940)

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, August 1928