Anita Garvin, Frances Lee, Estelle Bradley — Beauty Takes the Bumps! (1928) 🇺🇸

Lovely, laugh-getting ladies, Salomes of slapstick, unsung heroines of the custard pie and the “108,” beautiful damsels bereft of dignity, goddesses of the gag — the comedy girls. Give them a hand!

by Margaret Reid

The brief flash given the cast on a two-reeler leaves their names in obscurity to all but the quickest eye. The laughs they get are their sole glory, the one reward for bruises, sprains, and scratches. That is, of course, if one excepts the little — figurative — matter of salary. But the plaudits of the throng pass them by, these game, hard-working kids whose pulchritude would dazzle a Kleig.

Some of the most beautiful girls in Hollywood are in comedies. They have to be. In the fast shooting of a two-reel comic, there is no time for individual lighting, no thought for registering the best angle of profile, no fuzzy close-ups. Action is too quick to allow for charming poses, alluring expressions. A few hard lights to make the scene sharp and clear, the swift, direct movement of the gag, and that’s all. They need beauty to look entrancing under such conditions, and in such unflattering situations as the grotesque absurdity of a “108” — a complete flop which ends violently in a sitting posture on the floor, legs and arms flying.

Many a serial queen would blanch if required to perform the feats a comedy girl tosses off in a morning’s work. With either conscious or unconscious stoicism, they run the risk of breaking bones a dozen times during the two weeks’ course of a picture. On the screen their daring is not particularly obvious, because it culminates in a laugh. And the psychology of a laugh admits of nothing but just that — an explosive expression of amusement, with no undercurrents of alarm, or sympathy for the feminine vanity of the girl when the custard pie is thrown at her pretty face. Which is all as it should be. The girls themselves would be the last to deplore it. Laughs are the tickers by which they check the merit of their work. Pure, unadulterated guffaws are what they labor for. And these gorgeous-looking young things, whose perpetual aim and hope is to be laughed at, have an awful lot of fun on their own side.

Introducing three of the better known, and most beautiful — Miss Frances Lee, Miss Estelle Bradley, and Miss Anita Garvin.

Frances Lee

Frances Lee is the Christie pièce de résistance. The sweetly decorative ornament of innumerable Bobby Vernon comedies, she is now in a series of two-reelers called Confessions of a Chorus Girl. These are more or less polite comedy, but on the first day of work Frances wore roller skates, and had to take a sit-down bump that left her with a painful distaste for chairs for a week.

Frances is diminutive, cute, appealing. Neat little features without a flaw, wide, gray eyes, an inviting mouth and silky, light-brown hair. To say nothing of a figure that is a miniature Venus, modeled on 1928 lines.

Born in Minneapolis twenty years ago, Frances was intended, by parental decision, to be a school-teacher. Only Frances’ initiative saved that face and figure, and those dancing feet, from burial under a schoolmarm’s desk. At thirteen she began to study dancing in a neighborhood class. But in a few months she had left the other pupils to their Highland flings and sailors’ hornpipes, and gone far ahead. It became evident that her aptitude was more than a flair.

Within three years she was dancing professionally. Gus Edwards played in Minneapolis and wanted to sign her for his revue. But with precocious astuteness, Frances refused and remained at home instead, earning enough from local engagements to give herself a year at college.

Later, Edwards sent for her to come to Chicago and substitute for a member of his troupe who had fallen ill. After this engagement Frances turned down his offer of a contract. Staying in Chicago, she did soubrette work at the Rainbow Gardens cafe, where she was nicknamed The Baby of the Rainbow.

Billy Dooley, of vaudeville celebrity, visited the cafe in search of talent, spotted Frances and signed her as his partner. Their tour finally reached Los Angeles, where they were seen by Al Christie, who signed them both.

Considerable recognition has already been shown Frances. During a vacation from Christie’s she was lent to Fox for Chicken à la King. Her work in this so pleased executives that she was offered a five-year contract. Christie, however, retained her for the chorus-girl series, and she was philosophically content.

More than ordinarily sage for her years, Frances is ambitious in a sensible way.

“In this series,” she says, “I’ll have a chance to test whatever ability I have. I want to find out for myself just what my métier is. I never thought of myself as a comedienne, but they seem to think I have talent for it. My secret desire is for the sort of thing Janet Gaynor does. But I might not be able to do it at all. It is open for experiment. Whatever I do, I’d like it to be definite — either to make them laugh, or make them cry.”

After this series, in which she will have tried the former, she wants to have a fling at the latter. Being a sensible child, she will be satisfied if the experiment proves that her talent lies in the direction of comics and bumps. But being human and feminine, she would a little rather it fell in the more romantic area of the business

Estelle Bradley

Estelle Bradley flits decoratively through Educational comedies. She is a genuine blonde, pale-yellow hair framing a baby face. A round face, incredibly pink and white, decorated with very blue eyes, a delicately chiseled nose, and a mouth that can only, I am afraid, be described as rosebud. Though she uses very little make-up, even for the ruthless comedy camera, not a flaw can be noted. Technicolor was thought up for such as Estelle.

This angel was born in Atlanta, Georgia, twenty years ago. Of an untheatrical family, and with no particular yearnings for fame herself, the road to it was laid out before her — and carpeted into the bargain. To-day, grateful as she is for the ease with which everything has come to her, she feels vaguely guilty about it; that she has had all the breaks, where so many get only broken and battered.

At sixteen, she was elected Miss Atlanta for 1924. And, for once, a beauty-contest winner did crash through. I mean into pictures, not into waiting on tables in some boulevard restaurant.

The late Sam Warner, on a tour of investigation into the Warner Brothers’ business circuit, visited Atlanta. A dinner was given in his honor, at which Miss Atlanta, being the local headliner of the moment, was present. Warner observed the camera proof ness of the Bradley ensemble and, before the assembled company, made her an offer. If Miss Bradley would care to give pictures a trial, he would pay the expenses of her and her mother to Hollywood and, on her arrival, would guarantee her a stock engagement with Warner Brothers.

In Hollywood, Estelle found that Mr. Warner had arranged everything from New York, where he had gone. Immediately she went on salary. It was, however, the slack season at the studios, that annual lull following completion of the year’s schedule. Unwilling to put her in extra work, studio executives wanted to reserve her for the time when production should be in full swing. But Estelle was eager for actual exploration into this new-found interest. She wanted to work. Warner Brothers amiably agreed to let her search elsewhere. Hearing of the need for a leading lady at the Educational studio, she went after the job and — things happening that way to Estelle — got it.

It was the lead opposite Lige Conley, and her first work before the camera. Since that time she has been under contract to Educational, the fair-haired baby of the lot.

But although she did not have to work to get the contract, she has worked afterward. Docilely, this gentle youngster with the Southern drawl has fallen down wells, and into barrels of flour and off runaway automobiles. She has sat on cakes and pies, she has had soot thrown at her, been drenched by fire hose, and chased by ferocious animals. She has worked with dogs and, just as placidly, with leopards and tigers. And she has taken bumps and flops and falls of every known genre.

The science of the bumps was taught her by Charles Lamont, the young director who is now her husband. Lamont, during his boyhood in Europe, was a circus performer, and the lore of his early training in the ring has saved Estelle many an unnecessary bruise or sprain. Through him, she knows how to fall loosely, how to break certain bumps with the hands, at exactly what moment to relax or brace. She is an artist of the bumps, par excellence.

A few months after she began work for Educational, she was assigned to a picture under Lamont, with whom she had hitherto only a casual acquaintance. In a few days they were slipping off to lunch together. Two weeks later they were engaged. Three weeks after that they were married, and took a beautiful Spanish home in the foothills, over which the youthful Estelle presides with competence surprising in a comedy confection.

Anita Garvin

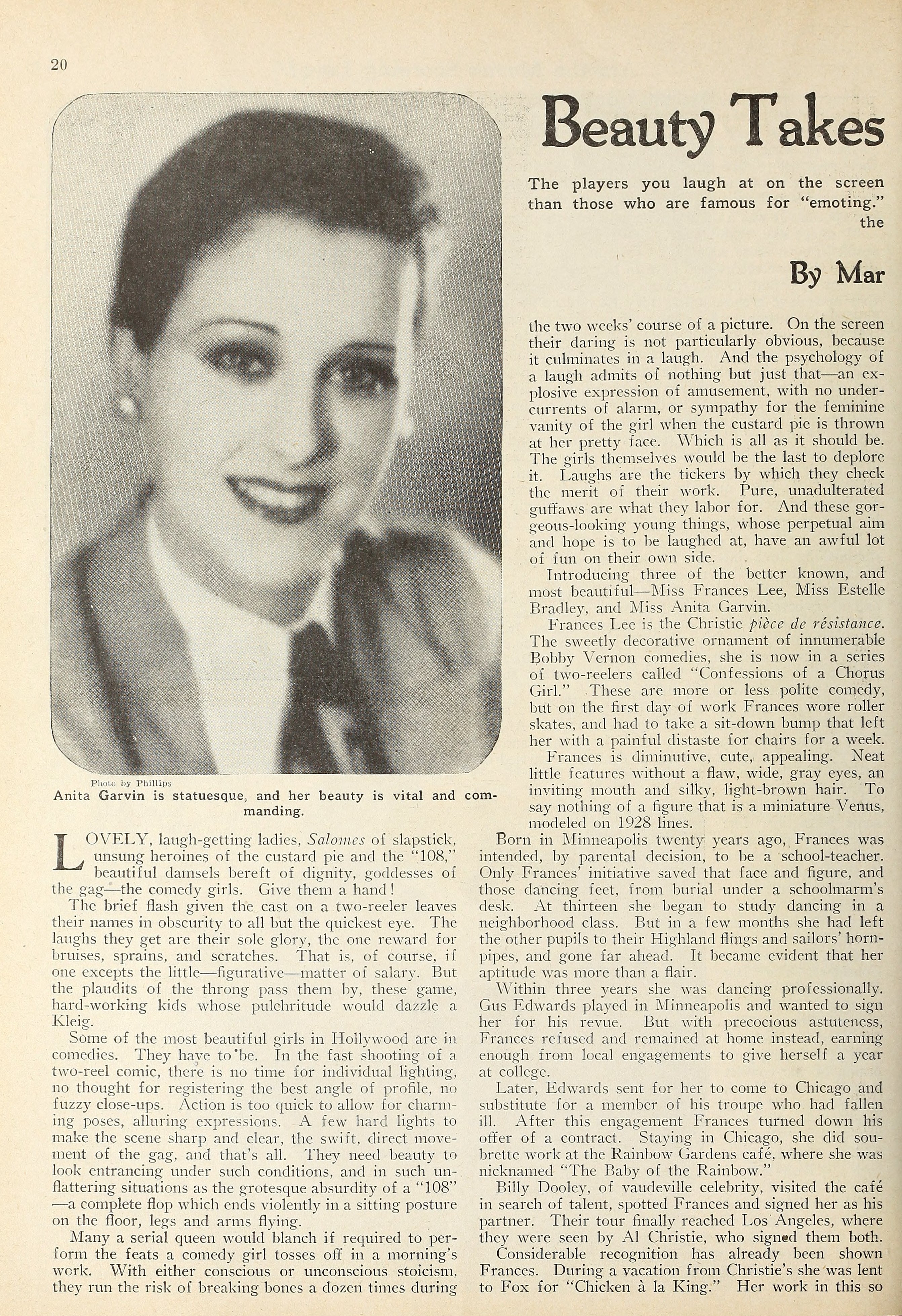

Anita Garvin, Estelle’s friend and confrere, is her pictorial opposite. Anita is statuesque. Her beauty is vital and commanding. Her slickly cropped hair is blue-black, and sweeping black lashes fringe her large, gray eyes. She has clear, pale-olive skin and sophisticated piquancy in the slight retroussé of her nose and the full curves of her mouth. She is essentially provocative — the come-hither lady for the susceptible comedy-hero. Being tall, she is in great demand as the opposite for comedians of small stature. Generally she wears the slinky satins of the burlesque vamp, and comes to an ignominious fate.

Born in New York, of Irish-American parents, she was screen and stage-struck from her kindergarten days. When she was twelve years old, while attending the Holy Cross Academy, she secretly ventured out into the grease-paint realm. Unknown to any one, she raided her sister’s wardrobe and dressed up in dead earnest. Her long hair hung in curls, which she did up in elaborate imitation of her sister’s coiffure. Being of the type which had developed, at twelve, into almost the duplicate of its appearance at twenty, she could pass, casually, for seventeen, which was the age she decided upon.

Teetering uncertainly on her sister’s high heels, she visited the office of a theatrical agent of whom she had heard. Arriving at nine in the morning, she waited Spartan until twelve thirty. The agent was in desperate search of one more girl for the “personal appearance” of Sennett bathing beauties in conjunction with the showing of “Yankee Doodle in Berlin.” He finally received Anita and opened the interview by asking what her previous experience had been. The only name Anita could conjure out of her nervousness was the Follies. Whether he believed her or not, the agent hired her and she went to work that afternoon, without rehearsal. On her way to the theater she stopped a stranger on the street and asked her the name of the stuff she used on her eyelashes. Purchasing mascara, powder and rouge, she hurried to the theater and excitedly applied a rather inaccurate make-up. Ten minutes before the curtain went up, the irate stage manager had some one ruthlessly scrub her face and make it up properly. That done, he ordered her to let her hair down and, trying to keep back the tears threatening her mascara, she had to sacrifice the intricate, grown-up coiffure by which she set such store.

From this engagement she progressed to bona-fide shows. She appeared in Sally, Irene, the Follies, and at the Winter Garden. At one time she modeled during the day, worked in Sally during the evening, and then did a midnight show.

During all this time, she had the movie bug in a bad way. In her spare moments, she haunted the studios — to no avail. It was the era of the petite type, and no one had a job for this tall kid who persistently begged for one. Heartlessly they told her to go home and study her algebra.

But Anita was not to be dissuaded. In the road company of “Sally” she reached San Francisco. There, with thirty-five dollars saved out of her salary, she left the show and came down to Hollywood. And at last the movies were willing to receive her. She got extra work at Christie’s and the first day on the set, Al Christie selected her from two hundred extras to do a bit. It was a Bobby Vernon comedy, and the bit was to slip on a piece of butter, and, with feet skidding upward, sit down heavily. That was Anita’s first bump, and her entrance into pictures.

She was put in stock at Christie’s, later leaving to play opposite Lupino Lane at Educational. After several Educational pictures, she went to Hal Roach’s for a brief period, but Educational recalled her at exactly four times her former salary. She alternates between Roach’s and Educational, preferring free-lancing to a contract. A pie is a pie to Anita. No matter what the studio, she gets it in the face anyway. And all studio floors are of equal hardness to the bump expert.

Anita has run the gamut of violent gags, even to having “breakaway” furniture crashed over her head. A few of her bumps have given her vacations in the hospital. But she does get the laughs. Instinctively a comedienne, she invents little bits of business of her own.

Lately, she has appeared in two or three Fox features, and in one Madge Bellamy picture [Bertha, the Sewing Machine Girl (1926)] attracted the notice of the critics.

Only twenty-one now, she has been married nearly three years to Clement Beauchamp, the Jerry Drew of Educational comedies. And, despite the old apprehension about two comedians in one family, they are still romantically in love.

Like the vaudevillians who dream of crashing a Broadway production, the two-reel players hanker after features. Both Anita and Estelle have the six-reel yen. Despite the hilarious fun they have making comedies, the urge for the more polite medium is beginning to make them restless. They have gained invaluable technical knowledge from their comedy training. Now they would like to take a step ahead. Anita would like, in some Utopian future, to do the sort of thing Pauline Frederick did. Estelle, on the other hand, wants human roles in light comedy.

The comedy field has produced many of our most famous players. It is a proficient school and its top scholars command attention. If only for this reason, make a note of the impending graduation of Estelle Bradley, Anita Garvin, and Frances Lee.

Graduate they surely will, for girls who are both beautiful and talented neither round out their careers in comedy, nor leave the screen altogether. The experience gained is too valuable to expend on two-reelers forever, and how many girls forsake the screen to marry Pittsburgh millionaires, as may be said of their sisters in the Follies?

Anita Garvin is statuesque, and her beauty is vital and commanding.

Photo by: Phillips

Frances Lee is giving her comedy talents a try-out, but she secretly hopes to do work similar to Janet Gaynor’s.

Estelle Bradley is one of the few to have crashed the gates of moviedom through having been a beauty-contest winner.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, December 1928