Tsuru Aoki — To One Lot of Kimonos — $25,000 (1921) 🇺🇸

I had almost decided to move to Japan and become a geisha, or a jinrikisha, or a ten don; not that I know exactly what these things are, but they sound delightfully Oriental and no doubt something that one could be without loss of dignity or prestige.

by Emma Lindsay Squier

My Nipponese inclinations were increased by hearing a missionary tell how rice is bought at two cents a keg; shoes at six cents a pair; parasols three cents per each, and lollipops, Japanese variety, at five for a cent. In view of the high cost of everything in America, it sounded attractive, and I might even now have been in the land of cherry blossoms and pigeon toes had it not been that Tsuru Aoki, who in private life is Mrs. Sessue Hayakawa, crushed my Oriental tendencies into utter oblivion under a huge pile of kimonos just brought from the flowery land of Japan. Not that she intended to discourage my craving for two-cent rice and six-cent shoes, but — wait and you shall see.

“This is very nice kimono for going to call,” she told me, spreading out a butterfly garment in which the hues of the rainbow, Joseph’s coat of many colors, and sunset in the Grand Canyon mingled flauntingly and audaciously.

“It isn’t so very expensive, it cost me one hundred and sixty yen — about forty dollars American money, but the obi,” she wrinkled her olive-tinted nose in an effort to recall the amount paid for the wonderful sash of heavy gold embroidery, “one hundred and fifty dollars American money.”

“One hundred and —” I gasped, and eyed with awe the golden five-yard sash that lay across Tsuru Aoki’s knees like the glittering skin of a Midas-touched serpent.

“One hundred and fifty dollars,” she repeated calmly, “just for sash.”

Her pronunciation, I noticed, was punctiliously correct, with only the faintest accent to remind one of her Japanese origin. Occasionally, she omits articles such as the, a, or an, but her vocabulary is a complete one, and her use of slang is thoroughly Occidental.

“It seems very expensive, does it not?” she continued. “But you cannot get one of any quality or beauty for less.” She spread it out for me to admire. “The gold embroidery is all done by hand, and,” she finished, as a clinching argument, “it is the same on both sides.”

It was indeed so; inside and out, from top to bottom, and from stem to stern, the Japanese sash was a network of golden threads upon heavy crimson silk. Its weight, as I held it in my hands, was tremendous; and when I thought of being wrapped in that five yards of gold-and-crimson grandeur, perhaps on a hot summer day — somehow the charms of Japanese life began to fade.

We were in the spacious library of the Hayakawa home. Tsuru Aoki, correctly and effectively tailored in American style, had spread out for my inspection a dozen or so of the ravishing kimonos and obis she had brought with her from Japan, where she had been visiting her parents after an absence of twenty years. Her jet-black hair was coiffed simply, but smartly, and there was nothing in her dress or manner to indicate her Oriental birth. Her bull terrier, whose Japanese name means “Fire-eater,” was also very much interested in the entrancing sartorial collection, and would have taken a more passive interest had his mistress permitted.

“I don’t know why it is that people think Japanese dress is cheap,” she went on, unfolding a symphony of gray and blue for my inspection. “You cannot get nice one for less than forty dollars, and many of them are as high as three hundred dollars; then the obis, as I have told you, are so expensive, and one must have a great many to keep in style.”

“To keep in style?” I echoed. “I thought Japan was a place that Dame Fashion didn’t bother with.”

“Indeed not,” she said decidedly. “A foreigner perhaps would never notice the change in style, but to Japanese, it is very apparent. The shape of the kimono and the width of the obi do not change from year to year, but the designs and materials differ almost as much as they do in America; for instance, this design” — she indicated the garment in her hands — “is very popular this year. These silver streaks are rain falling into the sea, represented by this gold embroidery, the white is for clouds, and these brown leaves mean that it is autumn, and the wind is blowing the leaves into the sea. It is a poem if you know how to read it. Next year, this design may not be used at all, and a lady wearing this kimono would be behind the times.”

She held up another, a rhapsodic mélange of gold-tailed roosters, vivid pink plum blossoms, dignified storks, light-green pine trees, writhing dragons, and zigzag lightning flashes.

The lining was of more fiery red than ever a boiled lobster or a ripe tomato could hope to achieve and was quilted heavily around the bottom.

“This is old court dress,” she explained. “When a Japanese lady is called to court, the empress presents her with a dress like this which she wears on ceremonial occasions. It has woven into it all the Japanese symbols of good fortune; stork for long life, dragon for wealth, plum blossoms for virtue, rooster for wisdom, and pine tree for a happy home.

“The pine needles, you see” — she indicated the embroidery with a tapering olive-hued finger — “are always in threes. That signifies to us the father, mother, and the child. And if a lady wore this dress at court, she might give it to her daughter to be married in. It would be very appropriate.”

When Tsuru Aoki visited the shops of Japan she found the merchants were ardent picture fans and very keen about selling her kimonos and obis for pictures, but they deducted not a yen from the original price — in fact, Mrs. Hayakawa suspects that some slight amount of profiteering was indulged in when it became known who she was.

Her collection of kimonos is valued at twenty-five thousand dollars, and she paid a duty of sixty per cent upon each garment and obi brought to this country.

“But it was worth it,” she assured me. “I purchased material in Japan that is impossible to get in America, and many of these kimonos will photograph beautifully. I will wear them in my next pictures.”

She showed me a marvelous garment of dull blue shading into old rose, which gave it the effect of batik. A gold-embroidered circle with a three-leaf clover on the shoulder was the only ornamentation.

“It is our family crest,” she said. “It is always correct to have the crest embroidered on the kimonos one wears for evening.” She pulled from the pile a heavy black kimono of marvelous crepe silk. The crest of the House of Hayakawa gleamed upon the shoulder.

“This is nice dress to wear for evening or for formal reception,” she told me. “In this country the greater the occasion, the more brightly you dress; in Japan, the greater the occasion, the more plain is the kimono.”

So now I know two things; one is why rice, shoes, and parasols in Japan are so inexpensive. When a Japanese husband finishes paying for his wife’s yearly wardrobe of kimonos and obis, rice and shoes have to be cheap, or Nippon would go foodless and shoeless. The other thing I know is that I shall remain in America.

“How many dresses would a Japanese lady of fashion have a year?” I inquired, still with a lingering Nipponese thought in the back of my mind.

“Oh, perhaps sixty — and, of course, each one would have an obi to match,” she added.

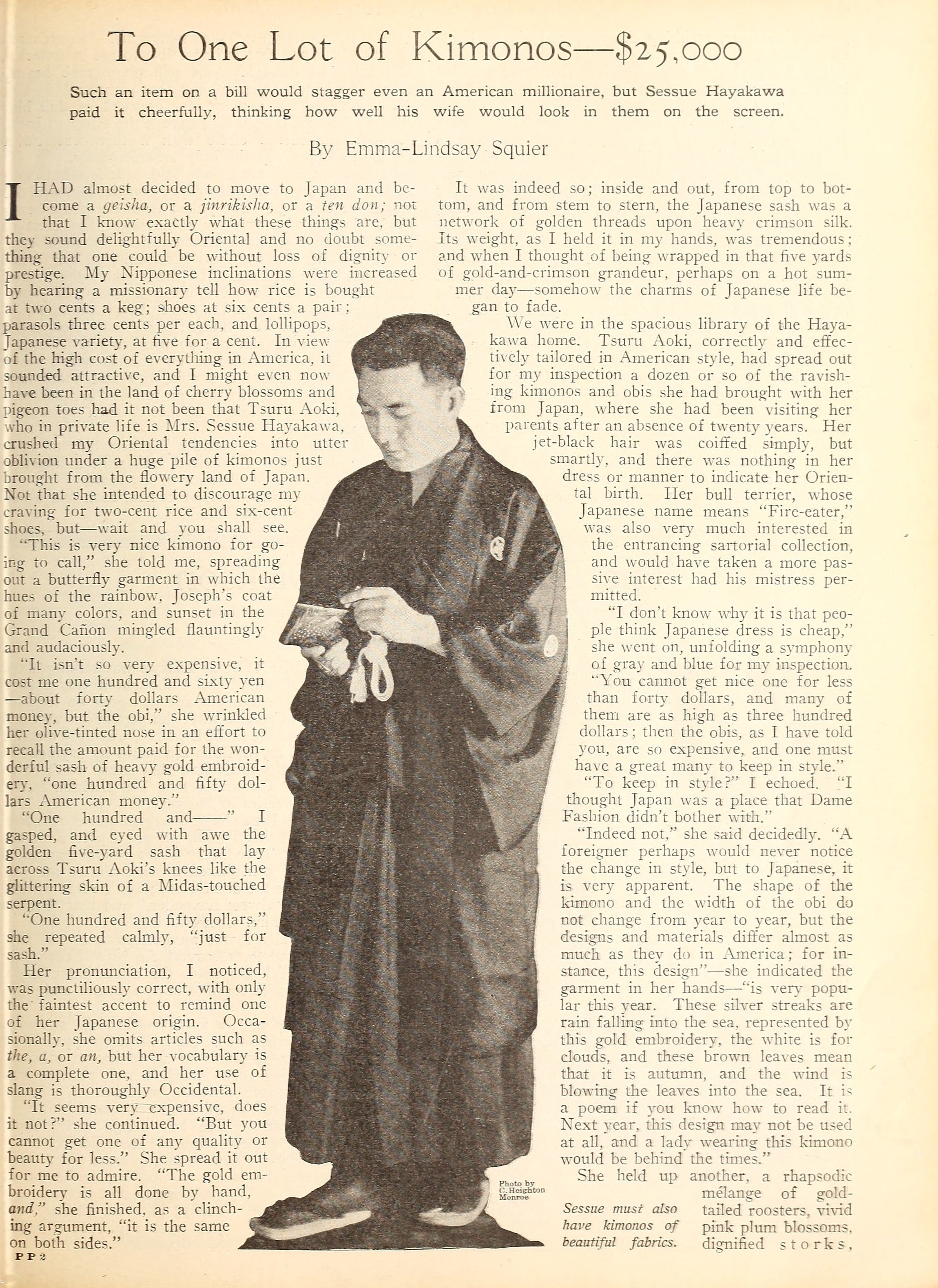

Sessue must also have kimonos of beautiful fabrics.

Photo by: C. Heighton Monroe

Tsuru Aoki wishes that this beautiful vase could appear to better advantage in her pictures. She has almost decided that she would like its design reproduced in embrodiery on one of her wonderful kimonos, about which you may learn some very interesting things by reading the story on the next page.

Photo by: C. Heighton Monroe

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, April 1921

---

see also this article about Japanese movie stars and movie-goers