“Katsudoshashin” (活動写真) (1929) 🇺🇸

American motion pictures have, in recent years, been an influence greater than any other in altering the daily mode of living of the people of Japan.

by Kimpei Sheba

The writer recently traveled three quarters of the way around the world, and believes he can safely say that no other people are being more immensely impressed and rapidly transformed by the movies than the Japanese.

In Shanghai and Singapore; in India, Egypt, and Italy; in France, Germany, and the British Isles, American photoplays are tremendously popular; but in these cities and nations it cannot be said that they serve any purpose other than that for which they are intended. The exception is in Japan.

In Nippon the customs of the people have been, in many respects, considerably altered since American films were introduced. Even the national psychology has been, to some extent, affected. The attitude of the people toward, and their knowledge of, the American and European races have improved to a startling degree.

Japan’s motion-picture companies have grown in the last four years from next to nothing, to one of the important industries of the land of cherry blossoms, and are producing to-day more feature-length photoplays than any country in the world, not excepting America.

Startling, this seems, but true nevertheless. In 1927 Japan produced more than one thousand feature-length pictures, the United States less than six hundred, and Germany but two hundred.

And this despite the fact that but ten per cent of the films produced in the far-eastern island empire end with a happy fade-out. Japanese pictures almost never end with the hero and the heroine in each other’s arms. The public wouldn’t stand for such a thing in a native picture.

They demand unhappy endings — fade-outs in which lovers are portrayed leaping into the bottomless pit of a waterfall, or the crater of a volcano, “to live happily ever afterward, in the next world.”

This, because the people of the Land of the Rising Sun find eternal happiness only in death. “Until death do us part,” to them becomes, “until death do us unite.” As love marriages still continue to be frowned upon, though this condition is changing rapidly as a result of the introduction of American movies, death is seen as the only happy ending of love.

Consequently, the majority of Japanese “love” pictures end unhappily. For this reason, perhaps, there is almost always crying in the movie houses — more crying, in fact, than is to be found anywhere outside of a funeral.

There are to-day thirty-six Japanese motion-picture studios. These companies produce a picture on an average of once a fortnight. Some pictures, however, have been completed in forty-eight hours. The record was’ thirty-six hours. Seventy-two hours later the picture had been cut, titled and censored and was being shown in one of the theaters in Tokyo.

American pictures naturally form the bulk of imported productions. Ardent love scenes are clipped, pictures of uprisings — especially those in which a crowned ruler is overthrown — are barred altogether, and blood in no form whatever is permissible. Censors have recently prohibited the showing of The Volga Boatman. They have scissored a considerable amount of footage from such pictures as Love and Flesh and the Devil.

This, however, is merely the preliminary censorship. After the films pass the central censorship board in Tokyo, they are examined by the prefectural police. Besides this, every theater in the country is equipped with a police officers’ booth. One officer occupies this booth at all times, and every picture shown is at his mercy. This officer has it in his discretion to delete any part of any picture.

As the films are sent to the various provinces, they are examined by the prefectural authorities, and by the time a picture of an amorous nature returns to the capital, it is about two thirds of its original length, if not less. In many instances, in fact, a picture has been cut to such an extent that it is difficult to follow the continuity of the story.

But here again the Japanese have a panacea. This is in the form of subtitle readers or translators, who, with their vivid descriptions supply audiences with a verbal picture of the scenes deleted by the censors.

The subtitle reader plays a very important part in Japanese theaters. What he says is forty per cent of the entertainment. He, moreover, has it in his power to make or break a picture. There are nearly ten thousand subtitle readers in Japan to-day.

These men have established their own schools of subtitle translating, just as jujutsu experts in olden Japan founded schools in which their method was taught, experimented with, and improved.

It may surprise movie fans of the United States to learn that while most of the subtitle reading in Japan is done in theaters, numerous phonograph records have been produced, on which the verbal descriptions of subtitle readers have been recorded. Another source of entertainment is listening to subtitle readers over the radio.

So vivid are the descriptions provided by some readers, over the radio and phonograph, that persons who have sat through one performance of a good picture can almost imagine seeing it over again, merely by listening to the subtitle reader.

Thus, instead of going to a theater twice, or even thrice, to view the same picture, a Japanese fan needs merely to purchase a record and run it in his home and be, figuratively, transported into a playhouse. The phonograph recording of an old picture, The Sea Beast, starring John Barrymore, was so vivid that tens of thousands of records have been sold.

Turning now to the influence which American pictures have had on Japan.

Most people acquainted with the Far East know that osculation was quite unknown to the Japanese before the introduction of American motion-pictures, and that kissing scenes in films were, until very recently, clipped by the censors. It probably will be surprising, therefore, to most readers, to be told that kissing is today widely practiced in Japan, and while not yet indulged in publicly, is done with considerable fervor and frequency in private.

Let us now turn to the matter of the kimono, the lovely national attire of the land of cherry blossoms, is fast disappearing, and in its place one finds to-day an array of American apparel. If one were to visit Japan to-day, he would no doubt be astonished, during even so brief a stay as a month, to perceive the constantly increasing number of girls who are doffing their native dress to appear in foreign costumes. The increase in the numbers of such girls is so noticeable, just at present, that few visitors have failed to observe this phase of changing Japan.

What has been the main factor in bringing about this situation? American movies, or, as the people of Japan put it, “katsudoshashin.”

While such a thing may sound incredible, it is, nevertheless, true that Japanese girls cannot, on discarding their kimonos and slipping into foreign attire, walk at all becomingly. Generations of squatting on floors, and the wearing of wooden clogs, have so disfigured their feet and legs as to make it almost impossible for them to walk faultlessly in foreign apparel, although of course they carry themselves gracefully, and with distinction, in their kimonos which hide their unshapely legs. A Japanese maid out of her kimono, in fact, may be likened to a duck out of the water, so awkward is her gait.

So, whenever opportunity presents itself, Miss Cho-Cho-San goes to the theater, there to closely observe the every movement of Greta Garbo or Norma Shearer, and painstakingly rehearse the “steps” — not dancing, but walking — that she has studied, on returning home, in an effort to affect a comely gait.

It may not be out of place here to state that there are numerous “specialist” fans — people who go to the theaters not to see movies, but, like the girls described in the foregoing paragraph, who go for some other specific reason. Many go to the theaters simply for the privilege of listening to, and memorizing, the musical scores; others study architecture and interior decoration; and still others are interested merely in pictures in which dancing scenes are included.

To what extent American pictures are indirectly influencing the Japanese people can, to some degree, be shown by stating that ninety per cent of the tunes one hears whistled, or played on instruments in the principal cities, were learned in motion-picture theaters, and that the majority of foreign residences that are being constructed were designed by architects, partly or wholly, after houses that they saw pictured.

As far as reading matter is concerned, almost a fifth of all American magazines imported into Japan are motion-picture periodicals. This may not seem astonishing, until it is stated that ninety per cent of those who purchase these magazines are unable to read them. Their only source of interest are the photographs.

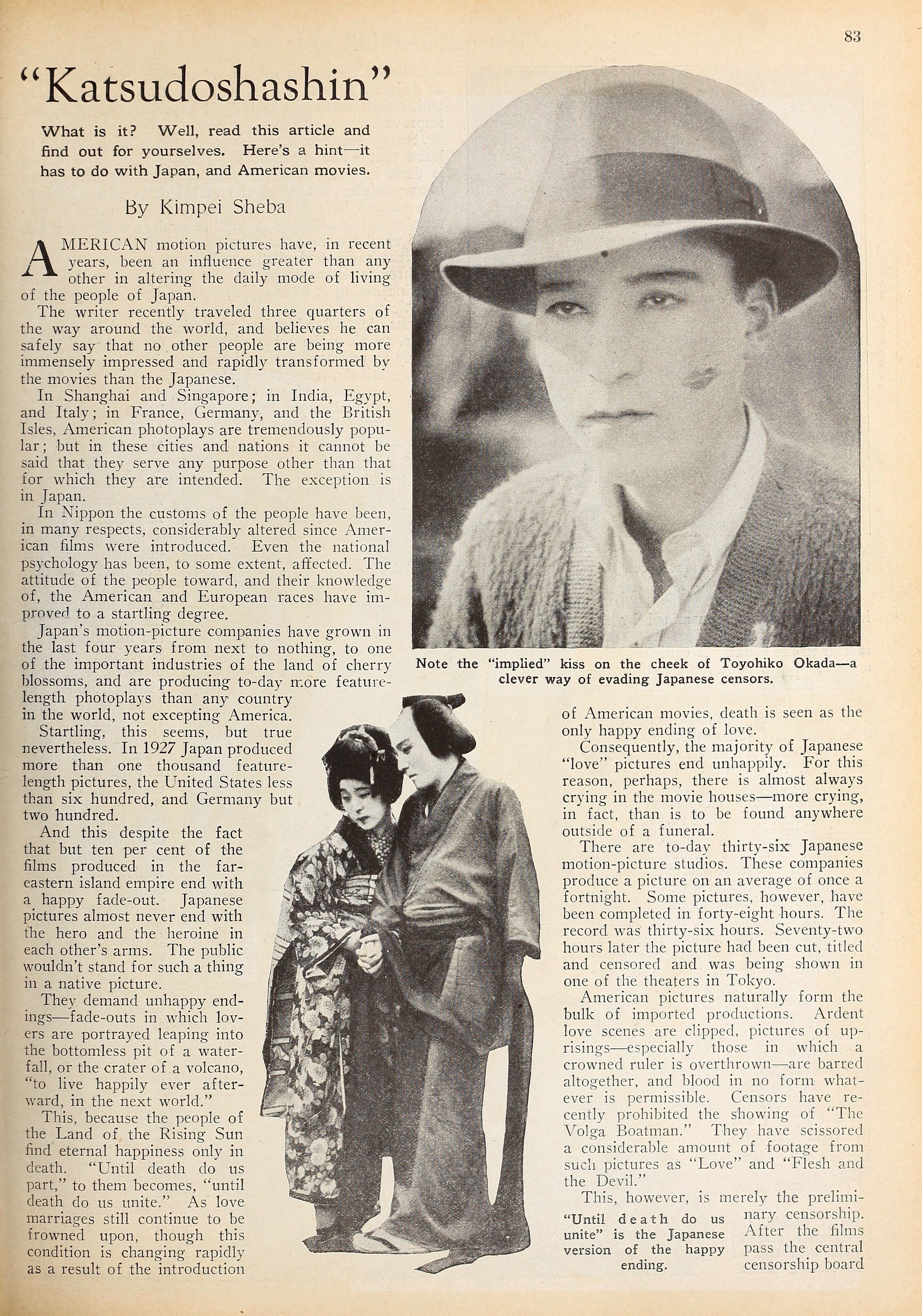

Note the “implied” kiss on the cheek of Toyohiko Okada — a clever way of evading Japanese censors.

“Until death do us unite” is the Japanese version of the happy ending.

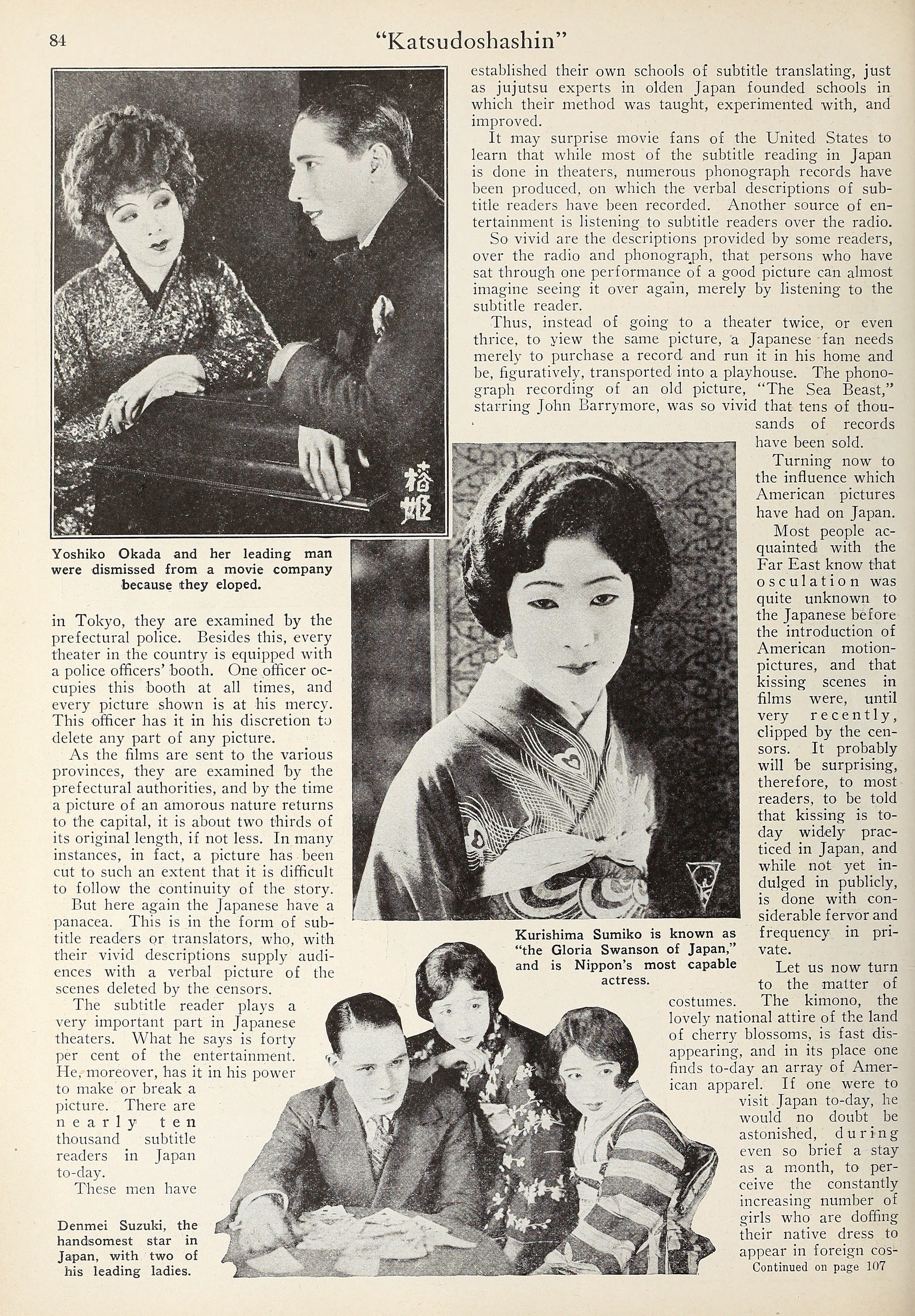

Yoshiko Okada and her leading man were dismissed from a movie company because they eloped.

Kurishima Sumiko is known as “the Gloria Swanson of Japan,” and is Nippon’s most capable actress.

Denmei Suzuki, the handsomest star in Japan, with two of his leading ladies.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, November 1928

---

Persons mentioned in this article:

- Tokihiko Okada (岡田 時彦) (1903–1934)

- Yoshiko Okada (岡田嘉子) (1902–1992)

- Sumiko Kurishima (栗島すみ子) (1902–1987)

- Denmei Suzuki (鈴木 傳明) (1900–1985)

- Kimpei Sheba (Journalist, Author)