Jack Mulhall — As He Is (1929) 🇺🇸

He once made a picture called Smile, Brother, Smile, which pointed a salesman’s philosophy of consistent, contagious good cheer. As an addition to the cinema it may not have ranked at the top, but as an expose of Jack Mulhall it was illuminating.

by Margaret Reid

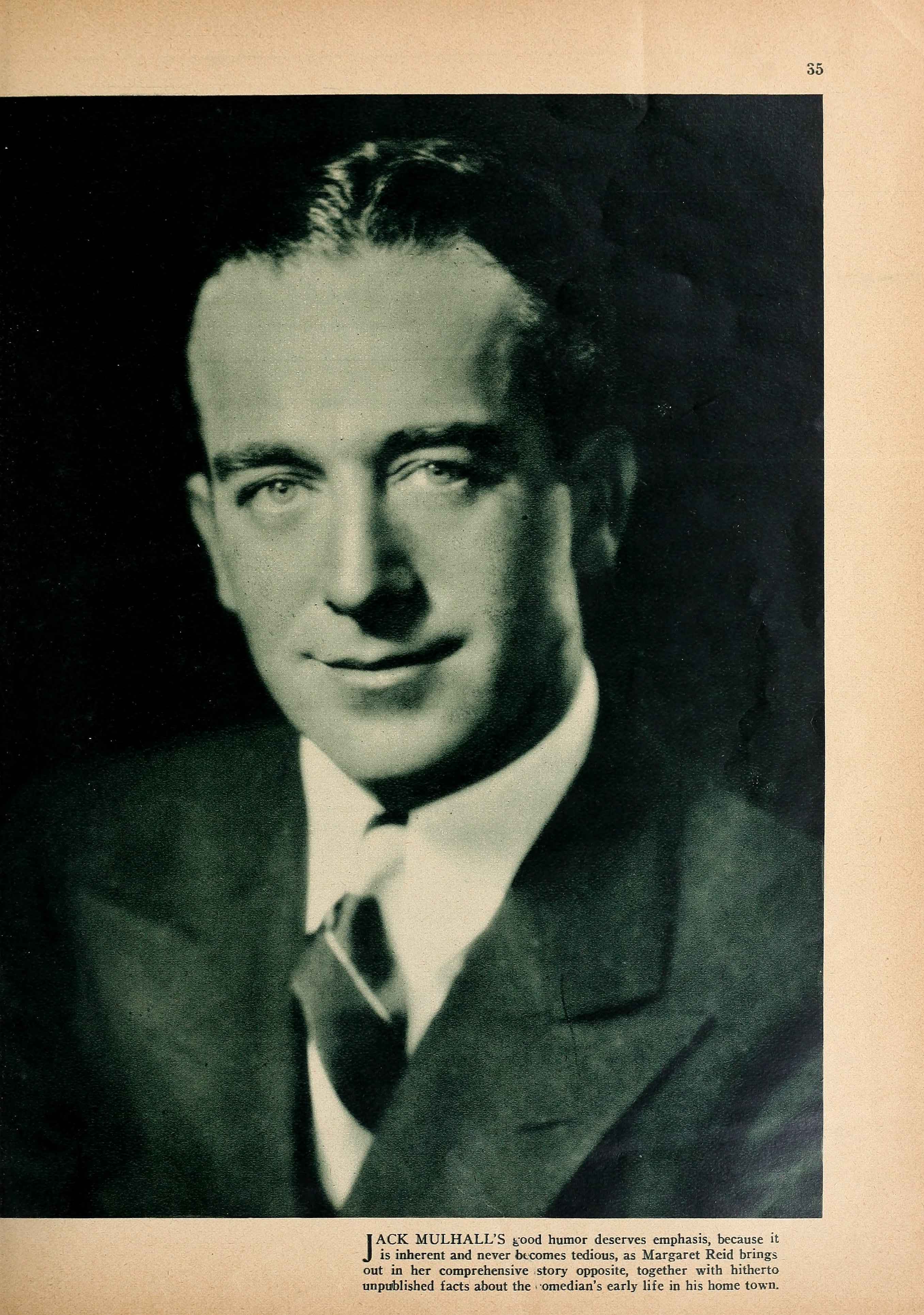

He is, literally and figuratively, the young man with the smile. Such theories are apt, in practice, to be more medicinal than pleasant to the world at large. Good humor in the wrong hands can be infinitely depressing. But Jack’s is infectious. It is, perhaps, less conscious good humor than unconscious good spirits, happiness, kindliness. His smile is omnipresent, but never tedious, because he means it.

Running boldly in the face of Hollywood tradition, he is an actor without a grievance. He is well content with his lot in life, and remains imperturbable in the midst of studio dissonance. People working in his company are at first inclined to discredit his sincerity. They think such a disposition can’t be real. But after they have seen it subjected to the hundred and one minor torments peculiar to studio routine, and still survive intact, they have seen it pass the supreme test. People who have once worked with Jack are thereafter miserable with any other troupe.

The morale of his company becomes dependent on him. The atmosphere of a set is almost a reflection of the star’s mood. The atmosphere on a Mulhall set never varies, and is a sure source of whoopee. Even those trying hours when work has been persisting for a day and a night, and weary nerves are beginning to snap, are not unbearable with Jack between scenes doing an impromptu “Florodora Sextet,” portraying all six sirens at once.

He is breezy, talkative, ingratiating. During an interview he has moments of shyness. When confronted with questions about himself, his face shows momentary panic, which he tries to cover by talking very fast. About himself he talks badly and with great rapidity, so as to get it done. On other topics he has the conversational charm and facility of the Irish.

Occasionally, in moments of excitement, his r’s still betray his ancestry. His forbears were Irish, but Jack was born in “Wappingersfallsdutchesscountynewyork.” His boyhood was a happy one. The summers he recalls as sheer, sustained bliss, principally because, from April to October, his shoes and stockings were put away and he wandered happily over the countryside, feeling the dust and grass between his toes.

The acting-bug attacked him early. His paramount interest in life — to be champion swimmer of the patrons of the “crick” up in the woods — suddenly paled into unimportance. The occasion was a school entertainment. Jack recited “I shot an arrow into the air” and, all at once, realized that he wanted to be an actor.

Later, when his family moved to Passaic, New Jersey, he hung around the theater, haunting the alley, and peering plaintively in at the stage door. No amount of dismissals could affect him. For policy’s sake he would go tractably away, returning a few minutes later with unabated curiosity. The stock company in possession at the time was financially embarrassed, and unable to pay rent for props. They needed an alarm clock for a certain scene, and wondered gloomily from where it would be forthcoming. Jack, eavesdropping brazenly from the alley, turned and sped out to the street and home, and back again. Hurling himself breathlessly in at the enchanted door, he thrust his father’s alarm clock into their hands.

This effected an entree for the young enthusiast. He regularly supplied them with what small incidentals, in the way of props, that he could sneak out of and back into the house without discovery. Difficulty, however, occurred when he was asked to bring some dishes. To his discomfort, these were not returned, but were smashed each day in a scene, and his mother was asking suspiciously where all her dishes were disappearing to.

Partly as a reward for his fervor, and partly to get him out from underfoot. Jack was finally given a bit — a page, in In the Palace of the King. Galahad in sight of the Grail knew no greater ecstasy than Jack’s on the opening night. His fourteen-year-old knees bulging knobbily under carelessly fitted tights, his shoulder blades giving his doublet a peculiar hang all its own, and his voluminous wig shifting uneasily at every step, Jack strode confidently onto the stage, thinking amusedly of Booth, who also was an actor. In a voice that, though it changed range unexpectedly, was charged with dramatic feeling, he began his one line and stepped forward.

The huge, fluted ruff around his neck obscuring his vision, he stumbled over a footstool and kicked it into the footlights. There was a bang, an explosion, two lights went out, and Jack stood paralyzed. Then from” the gallery, which was filled mostly with his pals, came a yell, “Hi — Mulhall!” In the hysteria born of excitement and terror, Jack began to giggle. Uncontrollably, and with the silly unreason of the awkward age, he stood riveted and giggling until the curtain was rung hastily down, and the stage manager grabbed him and administered as fine a whaling as the young Thespian had ever had.

His unfortunate debut did not dampen his ardor. Even to-day his pleasure in his job is as keen as it was then. He likes best to do human stories of average people, the little dramas of your next-door neighbor. He thinks that romance is just as real among everyday people as it is when ornamented by dinner coats and diamonds. And, for himself, he finds it most interesting.

Chaplin and Fairbanks are his idols. He considers Fairbanks a tremendous force for good, and believes that his pictures spread a sound philosophy more widely and more beautifully than all the works of Epictetus, Homer, et al.

Off a picture, Jack’s time is divided between the ocean and the golf course. He swims magnificently. His golf game, though energetic, is quite bad. He claims that the only way he could burn up a course would be with a can of kerosene. But the game is his passion, and he continues to enjoy it blithely. The one flaw in his inherent gentleness is the unappeased desire to kill those persons who wisecrack while some one is making a putt.

He has several distinguished relatives — doctors and lawyers. These do not figure frequently in his conversation, but no one can know Jack for two days that he doesn’t tell, with ill-concealed pride, about his brother Eddie who is engineer of the Wall Street Special, which runs between Tuxedo and New York, and who has the bronze nameplate on his engine which is the recognition of ten years’ faithful service.

He doesn’t talk about “his books.” His favorite reading is periodicals — Life, Judge, College Humor, The New Yorker, and Time, for which he discarded newspapers. His one highbrow weakness, to which he admits guardedly lest it appear an affectation, is paintings. Fine pictures reduce him to awe. Could he afford to indulge in such an expensive hobby, he would go in for serious collecting. His knowledge of painting and painters is extensive. He would like to be able to wield a brush, but cannot draw a straight line.

He thinks that education in the arts should be compulsory in American schools, as it is in Europe. He thinks that it is a mistake for the educational system here to concentrate on turning out good business men, the pupils thereby missing some of the greatest elements in life.

His eleven-year-old son shows promise of becoming a remarkable pianist. He has given recitals in Los Angeles, and is already famous among men who never heard of Jack. Jack is introduced as “John Mulhall’s father,” and glows with pride.

He likes well-made clothes, and has patronized one tailor for years. He always manages to look well-turned-out, without resembling a Boulevard fashion plate. His wife is one of the best-dressed femmes in Hollywood and together they make a stunning appearance at openings and restaurants.

He likes dogs and his idea of heaven is a place quite overrun with Aberdeens and wire-haired terriers. He also likes football, and after a game, is amused by the recollection of his collegiate, noisy abandon. He does not, on the other hand, like talking pictures, except when used for comedy, with long intervals of music and singing. But he is still open to argument, as the process improves, and is doing his second dialogue picture. The first he did fifteen years ago, when Edison was experimenting with records.

He likes California, but tires of the serenity of the climate. He likes to travel, and during his later boyhood took every cent he had made and went to Europe. There he reveled in the old towns and unfrequented byways until he was broke, and then worked his way back by shoveling coal on a tramp steamer. While he enjoys Europe and European customs, it is only as a spectator. America is his country, and he genuinely loves it — in spite of, he says, evangelists and Prohibition. Which is fitting, for if there is in this polyglot land such a thing as a hundred per cent American, Jack is it.

[a]

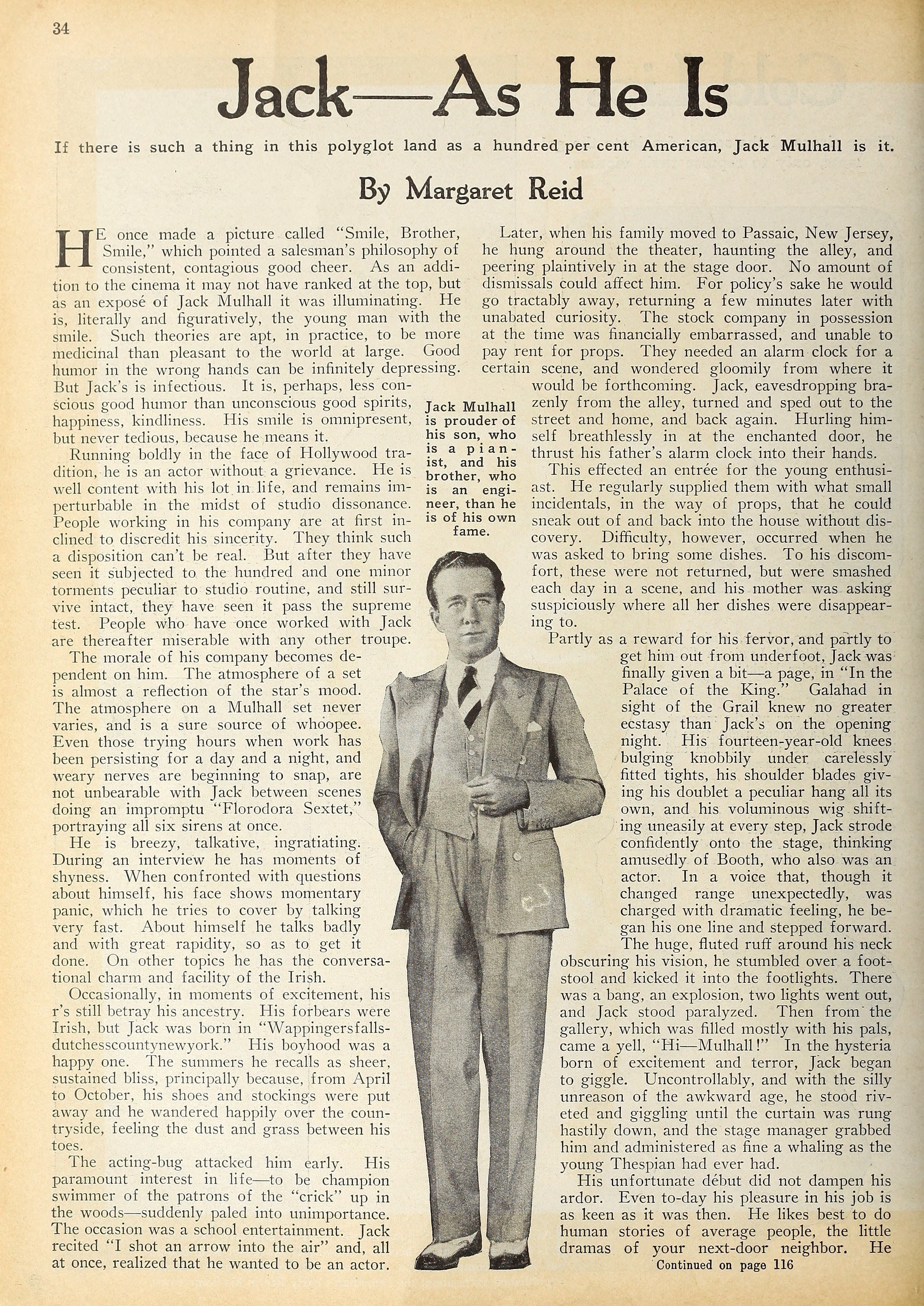

Jack Mulhall is prouder of his son, who is a pianist, and his brother, who is an engineer, than he is of his own fame.

Jack Mulhall’s good humor deserves emphasis, because it is inherent and never becomes tedious, as Margaret Reid brings out in her comprehensive story opposite, together with hitherto unpublished facts about the comedian’s early life in his home town.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, June 1929