Harry Langdon — Well, Sir, He’s a Scream (1927) 🇺🇸

As one who is weary of the more or less somber leading men — the Norman Kerrys, the Rod La Rocques, the Thomas Meighans, the Milton Sillses; as one who would willingly give these and other pictorial gents a long vacation, I am all for comedy. Comedy has been coming into its own: nothing suits me better.

by Malcolm H. Oettinger

Give me a soft-enough seat, and show me a “deadpan” artist with wistfulness, whimsy, and a bag of gags, and I’ll stop saying all those nasty things about Ramon Novarro, “Bull” Montana, and Rin-Tin-Tin. Give me, for instance, Harry Langdon.

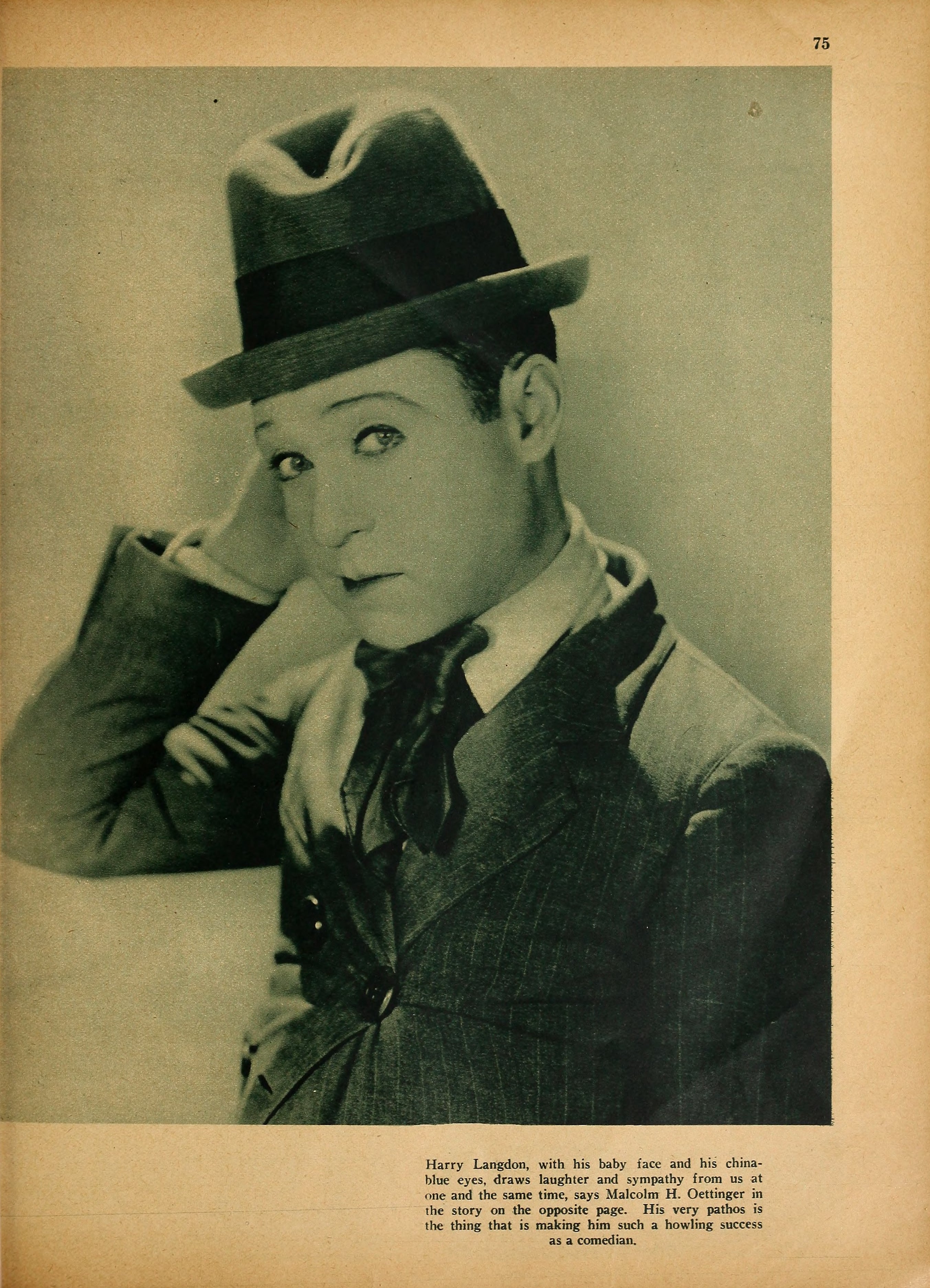

This little fellow with the baby face and oversized trousers has been growing slowly, serenely, surely, into one of our leading laugh producers. He has become the Belasco of the giggle, Frohman of the guffaw, Griffith of the belly laugh. He has developed an original style, nurturing it under the watchful eye of Professor Sennett [Mack Sennett], cultivating it evenings among his books, I dare say, until to-day he is blossoming gradually, gracefully, into a dominant star of snicker epics.

First, Chaplin [Charles Chaplin] ruled alone. Then a smart young man stepped out of the split reels and joined his select group. That was Harold Lloyd. Then, another sprightly jester ambled into view, also graduating from two-reel snacks into six-reel banquets: the droll Keaton.

The others have made comedies — Lloyd Hamilton, Larry Semon, Neal Burns, Lige Conley — run of the mill, sorry attempts for the great part. For the past two or three years Lloyd and Keaton have sat at the foot of Chaplin’s throne. Charlie has remained preeminent even with a single picture a year, but Lloyd has made consistently appealing, briskly paced pictures. And Buster Keaton has occasionally turned out a model mirth maker — The Navigator, for example.

Meanwhile, a fourth figure has been hovering about the horizon, almost timidly knocking at the doors of our theaters, shuffling uneasily onto the screen. A shy, wistful miniature, with the gift of pathos and a sure touch in expressive pantomime — this is Langdon. From grammar school Langdon found his way back stage to do odd chores. Before many years had passed he was a member — unimportant, but still a member — of an itinerant troupe that called itself a vaudeville act. Sometimes, when fortune smiled, they actually played in vaudeville theaters. At other times, which was oftener, they disported in side shows, in carnivals, in the minor circuses.

It was from this gypsy life that Langdon sprang into variety halls with his own act. He called it Harry’s Car, and played it up and down the country for six years or more. He wasn’t what is technically known as a headliner by several hundred dollars, but his was a standard act, good for a booking every season. Managers found that audiences welcomed his act again and again.

When he was playing in Los Angeles one summer, Mack Sennett idled into the Orpheum one afternoon, clapped eyes on the diminutive comedian, and his doom was celluloid.

The series of comic strips that Harry made for the raucous Sennett ran what a more pretentious chronicle might term the gamut. Some were fairly Alaskan in locale, others tropical, some Manhattan, others Bronx.

Now Harry was a noble white wing, now a humble bartender. This week he impersonated a traffic cop, next week a carefree tramp. Almost all these were funny pictures; some were hilarious. One of the best was a burlesque of The Girl of the Golden West.

Throughout these two years of apprenticeship at the giggle and guffaw foundry, Langdon progressed steadily, ever showing promise of what was to come. Many of us watched for the Langdon “added attraction,” hurried to see him, and made our get-away before the super-superfeature, super-superfeaturing Mae Murray or Colleen Moore, began unreeling. Many theaters billed the brief Langdon comedies over the main picture.

Other producers became interested. When the Sennett contract expired Langdon was signed by First National to make feature-length pictures. The first two were howling successes, and howling is the word.

In Tramp, Tramp, Tramp pathos was permitted to creep in ever so gently, to be whisked away before the thing grew serious. The timing in this first ambitious effort was always right, the gagging was spontaneous, the characterization never forgotten.

Of course, Langdon depends upon situation to a large extent, but his is the gift for interesting subjectively, as Chaplin does, rather than objectively, as Keaton and Lloyd do. You laugh at what the latter do, but your mirth at a Langdon or Chaplin film is inspired by what happens to them.

The one school depends almost solely upon outside aid — breakaway ladders and fall-apart suits, and chases — while the other school holds your attention with a hundred, two hundred, feet of quiet, adroit pantomime.

Who will forget the severe cold that afflicted the patient Langdon in The Strong Man? Who will forget the eloquent love scene played to the girl on the billboard in Tramp, Tramp, Tramp? Who will fail to recall, in that same picture, his attack of insomnia? Or his flirtation in The Strong Man? All four of these sequences were based upon a genuine talent rather than a shrewd gag.

Langdon’s curly mop of hair, his plump face, curiously devoid of expression save it be sadness, his china-blue eyes, his artful hands, all serve to build a strong, sympathetic bond between him and his audience. Just as Lloyd personifies the up-and-doing young man we all know, so does Harry Langdon remind us of the little boy across the street. Indeed, in the final, amazing scene of Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, he reminded us of the baby next door, so genuinely did he counterfeit the tremors and twitchings of infancy.

Although one is tempted to call him a dead-pan comedian, the appellation is erroneous. Keaton, of course, is a dead-pan artist, relying upon his wooden expression to get across many gags.

Langdon employs the witless gaze only occasionally. As a rule, he uses facial expression, aided by his extraordinary hands. He has taken a leaf from the great Chaplin by learning the effectiveness of hands in pictures. Only one other comedian uses them to effect, and he is the erratic Lloyd Hamilton, whose very bad comedies serve to offset his rare good ones.

Langdon combines the ludicrous and the pathetic in a single continuous gesture — a sweep of the hand, perhaps, that starts to explain some question, or dispel some problem, only to wind up in a helpless, little twist of the wrist, a twist fairly capturing the futility of things.

His gayety is always tinged with doubt; he stands for the average human being, his hopes, his fears, his aspirations, his lack of confidence, his dreams. The Langdon pan is a mirror of longing. Consider this far-fetched, if you like, but first see The Strong Man.

Chaplin is still at the head of the list, supreme comedian of the screen. But close upon his heels patters grave, grotesque Harry Langdon, with his saucerlike eyes in his moon of a face, with his tortured, little smile and his fluttering hands — Langdon who is fast passing Lloyd and Keaton in the race for popularity.

When a man succeeds in getting laughs and winning sympathy at the same time, he may safely be said to have arrived. By this token, Harry Langdon is here to stay!

Phantom Red Lipstick

The Shade Paris is Raving Over!

created for Mary Philbin, Universal Star

Harry Langdon, with his baby face and his china-blue eyes, draws laughter and sympathy from us at one and the same time, says Malcolm H. Oettinger in the story on the opposite page. His very pathos is the thing that is making him such a howling success as a comedian.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, April 1927