Has Success Changed Ben Lyon? (1927) 🇺🇸

Four years ago the writer had an interview with an obscure young newcomer to the films. His name was Ben Lyon, and the interview was his very first for publication in a motion-picture magazine.

by Alma Talley

He had been playing the juvenile lead in Mary the Third on the stage, his first Broadway appearance after several years of stock and road companies. Samuel Goldwyn had seen him in that play and had given him a part, in the film version of Potash and Perlmutter.

Ben had just finished the picture and was leaving for California when the interview took place. He was then twenty-three, a black-haired boy with merry, deep-blue eyes, a slight Southern accent, a delightfully jolly manner, and a natural wit which made him a most amusing companion.

He was then, perhaps, a little naive, showing me photographs of his dog, of his former home in Baltimore, and talking earnestly of his future. He had been making three — or perhaps it was four — hundred dollars a week in Potash and Perlmutter — the most he had ever made. And now that the picture was finished, Samuel Goldwyn was sending him on his way to California, with the Goldwyn blessing and a letter of introduction in his pocket.

Ben was very much thrilled by all this — “Young Man Makes Good.” The future looked rosy; perhaps his career had definitely turned the corner toward prosperity, and there would be no more lean years of one-night stands in road shows, with bad food, bad hotels, bad railroad accommodations. Ben hoped all that was past.

This happens to be a story of dreams come true. All that was past. When I went to see him recently, I was reminded of one of those “before and after” ads. Ben had taken a close of fame in the meanwhile, and it seemed to have agreed with him very well.

The interview took place in Ben’s marine-blue car, in and out of which he dashed between shots on location. He was wearing a handsome tweed topcoat. His face was rounder, fuller — looking, naturally, a little more mature. Self-assurance, greater sophistication, had come with success. Otherwise Ben is much the same witty boy he used to be, with that merry twinkle in his eyes — still the life of the party, still somewhat of a prankster.

His press agent, who was with us, pulled out a package of a new brand of cigarettes.

“Well, well,” said Ben, “you answer all the ads, don’t you?” And I knew at once that, if I only shut my eves to the new car, Ben hadn’t changed a bit.

The company — Ben, Sam Hardy, a few minor players, and dozens of electricians, camera men and prop men — was on location, taking street scenes for High Hat. It was in the Harlem section of New York, where the company had rented an empty building and plastered it with signs, designating it a Greenwich Village restaurant — “The Blue Cow Cafe. Dining and Dancing.” Across the narrow street from the building were cameras, and noisy sunlight arcs mounted on trucks.

Ben’s car was parked up the street a little, and he had invited us to “step into his dressing room.”

He was just finishing the picture prior to his departure for California a few days later. The interview was rather an intermittent affair, so this is mainly a story of just what Ben is like personally.

I offered him congratulations on his work in The Prince of Tempters, which had just been hailed by a highbrow critic as one of the ten best performances of the year.

“That’s because Lothar Mendes, the director, knew how to guide his players,” Ben said emphatically. “Every time I work under a director who tells me exactly what to do, I get good notices. Yet you’d be surprised how often directors let actors do things their own way; the result is that one man is overplaying, another is underplaying, and you have farce, drama, burlesque, all in one picture. I can’t get any perspective on my own work — it’s the director’s job to get the perspective. He knows just what effects he is after in each scene — at least he should know — and he should see to it that the players are pulling together, rather than in different directions. It’s just the same with an orchestra leader — it’s the man with the baton whose job it is to control the ensemble.”

At this point the press agent put in that Ben had had considerable training years ago in Jessie Bonstelle’s stock company, and that it was too bad that he was always being cast in roles in which he had no opportunity to display any histrionic ability. Usually, he’s cast as a good-looking young man who merely walks through the picture.

“The fans certainly know the difference when I have a real role to play,” Ben said. “My mail increased a lot after The Prince of Tempters — the letters actually increased at the rate of two hundred a day. Imagine that! From an average of four hundred and fifty to six hundred and fifty. Charming letters, some of them. You’d be surprised, the different kinds of people who write — young girls, mothers, grandmothers.”

The very fact that he’s the sort of young man of whom both very young girls and their mothers seem to approve, makes Ben doubtful if he is appropriately cast in the “sexy” roles he is so often given. It’s odd that he should get mash notes and letters from girls’ mothers as well as from the girls themselves.

“But, gee! that fan mail is expensive,” Ben said, somewhat ruefully, though obviously the letters mean a lot to him. “I have to pay salaries to two secretaries; and last week I handed out ninety dollars for postage stamps, and the week before one hundred and twenty. The fans have no idea how much it costs to send out photos, and few ever think of sending a quarter.”

At this moment a call came for Ben to go back before the camera.

“Hungry?” he asked, as he left. “I hope this will be the last shot.”

Hungry! It was long past one o’clock and every one was starving. The company was trying to finish the location shots before returning to the studio for lunch.

“Ben wants to know if you’d like some of this cheese.” A prop man stuck his head in the window of the car. Would we! We seized two little triangles wrapped in tinfoil and opened them greedily. Inside each was a little — block of wood! Ben was at it again. Still a prankster.

He came back then, with a long, jagged tear in his topcoat. “One hundred and fifty for that coat,” he declared in dismay, while a prop man came over to take it to be mended for the rest of the sequence. There had been a scene in which Ben had been dragged into an automobile, and the coat had been torn in the rough-house.

“I’ve never had any big specials to play in,” Ben remarked, “like The Big Parade or Beau Geste. But there’s one consolation about it. The exhibitors in small towns can’t afford to pay the big rentals asked for such specials, but they can always afford program pictures, so my films are shown in every little village in the country.”

Which is quite true. Ben is known even in the tiniest hamlets in America, where, frequently — and this is actual fact — John Barrymore has never been heard of.

Yes, Ben is still the same boy, a little concerned about his future, the size of his fan mail, and what the critics think of him — not because of vanity, but because such things offer an indication of how your career is progressing.

Large groups of street urchins were clamoring upon the running boards of Ben’s car, gazing at him in admiration. He has learned in these years not to be embarrassed by such gawking. Perhaps you think it would not be embarrassing to have crowds follow you on the street, staring at you as if you were a freak from the circus!

There was another call for Ben on the set. When he next came back he sat down and banged the door in annoyance.

“I’m going to get temperamental!” he declared. The press agent and I sat up eagerly, thinking perhaps he was going to strike for some lunch. But no, it wasn’t that.

“If they think I’m going to take close-ups in this light, they’re mistaken! They take a lot of close-ups on a cloudy day like this and tell me they won’t be used if they’re no good. But when the picture comes out, there they are! And I look like the devil in them. And the critics say, ‘Well, well, too many late hours for Ben.’ There has to be good lighting for a close-up to look like anything, and I’ve fallen for that ‘won’t be used’ gag often enough!”

[Text missing] …actor, came over. “You’re wanted, Ben.”

“I’m not going to take close-ups — not unless the sun comes out,” said Ben.

Then came the director himself, James Ashmore Creelman. He sat down in the front seat beside Ben. “Now listen,” he said soothingly, “I’m just as anxious as you are for these close-ups to be good. The camera man says he can do it, and if he thinks it’s all right, don’t you think you and I ought to take his word for it?” He spoke in tones one might use to mollify a small child. “If they’re not good, I won’t use them — I promise you.”

“Is that a go?” Ben brightened.

“Absolutely; I swear it.”

So Ben clambered out again to take the close-ups. Don’t blame him for the little outburst; his point was perfectly well taken. Besides, it was two thirty, and he was starved and cold and tired. Working in the movies is not fun — it’s a series of petty annoyances, as any one will tell you after spending an hour on the lot.

This Ben Lyon who can stand up for his rights has progressed a long way from the boyish Ben who went through all sorts of hardships at the beginning of his career. It amuses him now to look back on those days when he traveled from one town to another on the milk train.

“The one morning train in those places was never later than six thirty,” Ben explained. “And we made so many towns so fast that, honestly, if some one asked you where you had played the night before you couldn’t remember.”

This was with the road show of Seventeen, back in 1919. The best hotel in some of the towns was fifty cents a night and couldn’t have been worse.

Ben likes now to laugh at those days, which were no laughing matter at the time. Days of discomfort, when he would have starved if a check from the family hadn’t arrived at crucial moments. Now it is he who gives the family money instead of receiving it, though his family is in very comfortable circumstances. He has several married sisters, and a brother who sells insurance. Ben is the baby of the family, the boy grown older, yet very much the same boy, despite his fame, as he was at that very first interview, four years ago.

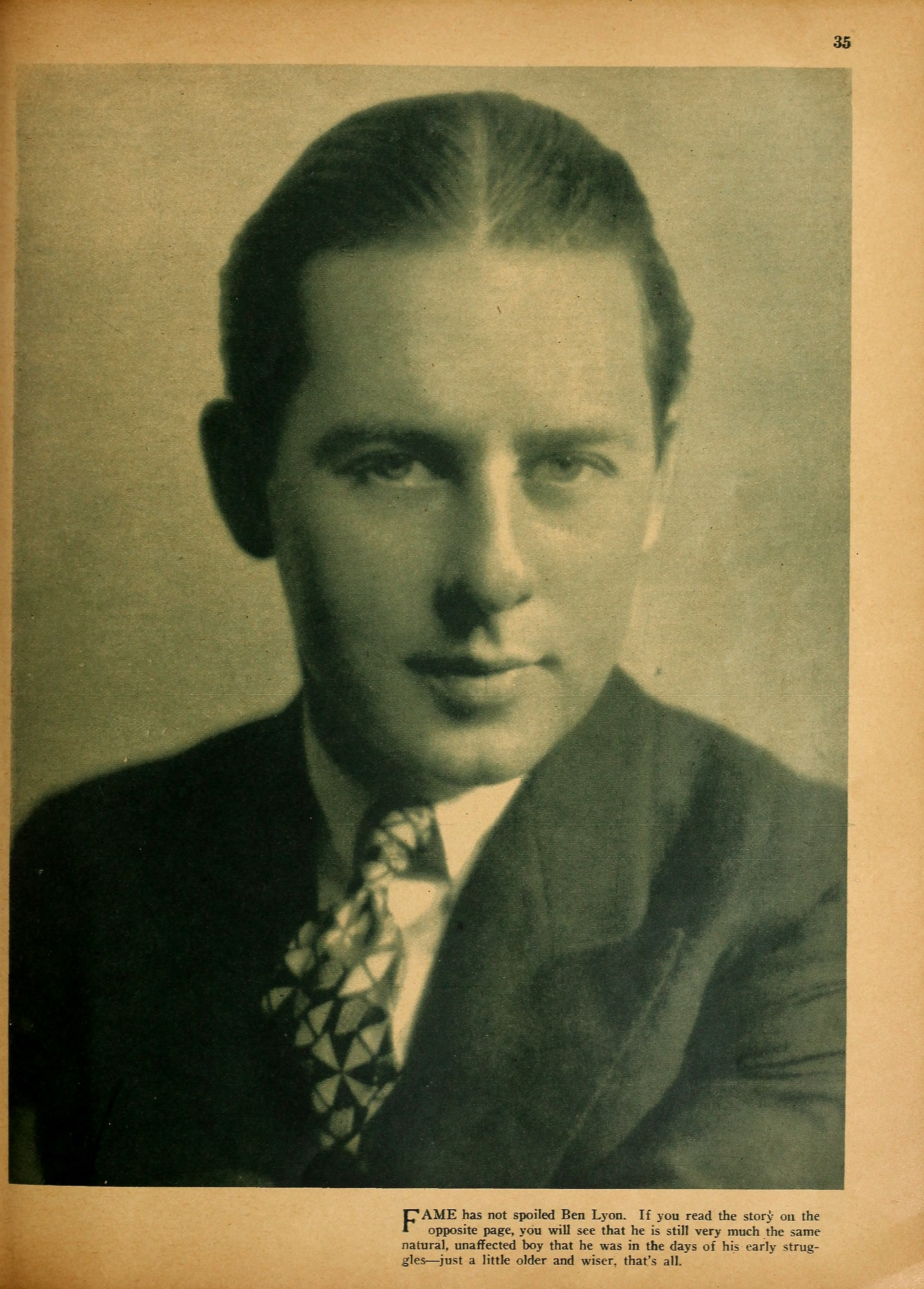

Fame has not spoiled Ben Lyon. If you read the story on the opposite page, you will see that he is still very much the same natural, unaffected boy that he was in the days of his early struggles — just a little older and wiser, that’s all.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, May 1927