The Stepchildren Make Whoopee (1929) 🇺🇸

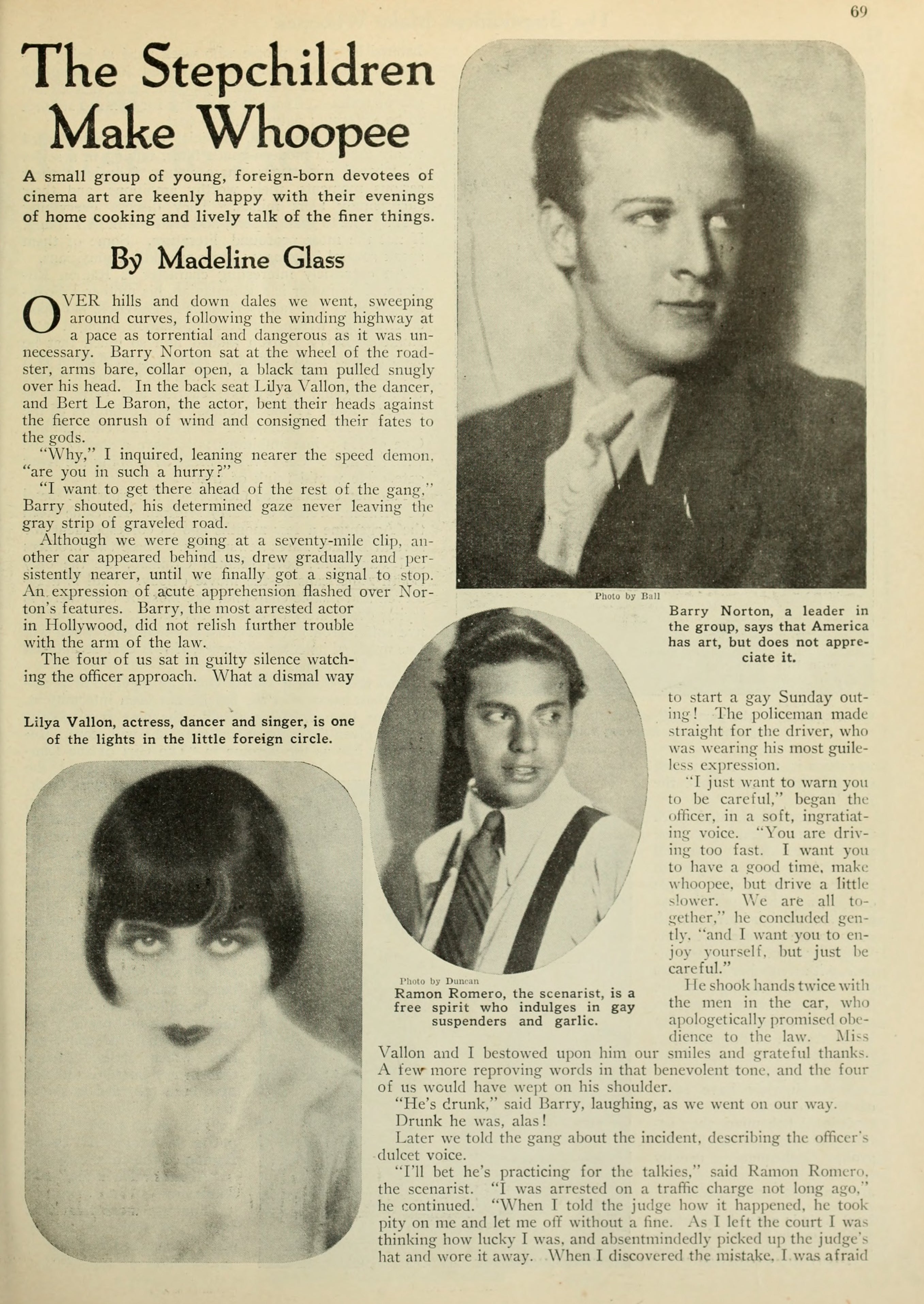

Over hills and down dales we went, sweeping around curves, following the winding highway at a pace as torrential and dangerous as it was unnecessary. Barry Norton sat at the wheel of the roadster, arms bare, collar open, a black tarn pulled snugly over his head. In the back seat Lilya Vallon, the dancer, and Bert Le Baron, the actor, bent their heads against the fierce onrush of wind and consigned their fates to the gods.

by Madeline Glass

“Why,” I inquired, leaning nearer the speed demon, “are you in such a hurry?”

“I want to get there ahead of the rest of the gang.” Barry shouted, his determined gaze never leaving the gray strip of graveled road.

Although we were going at a seventy-mile clip, another car appeared behind us, drew gradually and persistently nearer, until we finally got a signal to stop. An expression of acute apprehension flashed over Norton’s features. Barry, the most arrested actor in Hollywood, did not relish further trouble with the arm of the law.

The four of us sat in guilty silence watching the officer approach. What a dismal way to start a gay Sunday outing! The policeman made straight for the driver, who was wearing his most guileless expression.

“I just want to warn you to be careful,” began the officer, in a soft, ingratiating voice. “You are driving too fast. I want you to have a good time, make whoopee, hut drive a little slower. We are all together,” he concluded gently, “and I want you to enjoy yourself, but just he careful.”

He shook hands twice with the men in the car, who apologetically promised obedience to the law. Miss Vallon and I bestowed upon him our smiles and grateful thanks. A few more reproving words in that benevolent tone and the four of us would have wept on his shoulder.

“He’s drunk,” said Barry, laughing, as we went on our way.

Drunk he was, alas!

Later we told the gang about the incident, describing the officer’s dulcet voice.

“I’ll bet he’s practicing for the talkies,” said Ramon Romero, the scenarist. “I was arrested on a traffic charge not long ago,” he continued. “When I told the judge how it happened, he took pity on me and let me off without a line. As I left the court I was thinking bow lucky I was, and absentmindedly picked up the judge’s hat and wore it away. When I discovered the mistake. I was afraid to return it, as he might have changed his mind about the fine.”

I became acquainted with them about a year ago, these playful, reckless, mercurial stepchildren of Hollywood. Nearly all the young people comprising this particular gang are foreign born, and all of them are pursuing a career. Actors and actresses predominate, with a number of writers and dancers lending variety. Their lives sweep along on precarious artistic seas, to-day in the trough of despondency, to-morrow on the crest of optimism and good fortune.

Although they have some of the characteristics of the traditional bohemian, they actually do not belong in that group. Bohemianism usually is indicated by bizarre studios and sunless apartments, inhabited by young people who work hard at being different. The bohemians of Hollywood, if one may call them such, are surrounded by beaches and sunsets and gay bungalows. It is not necessary for them to attempt to be different; nature saw to that.

Unlike the annoying, artificial puppets who raced wildly through modern-youth films, talking in a series of labored wisecracks, these young folk have their serious moments, their worthy ambitions, and their surprisingly alert minds. They discuss everything from garlic to grand opera, and read the most striking, if not the most profound, literature. Some of them speak several languages; some are skilled musicians.

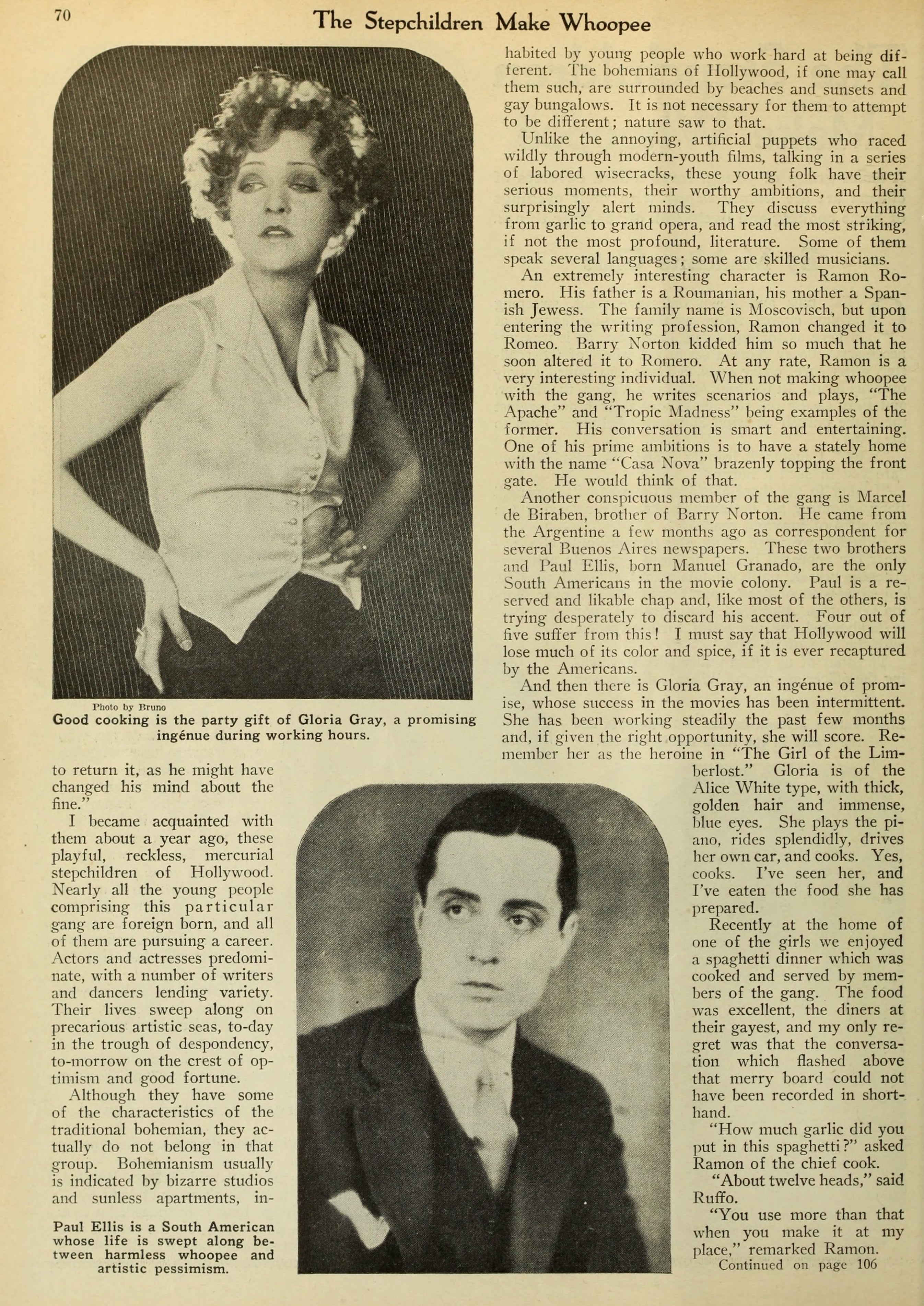

An extremely interesting character is Ramon Romero. His father is a Roumanian, his mother a Spanish Jewess. The family name is Moscovisch, but upon entering the writing profession, Ramon changed it to Romeo. Barry Norton kidded him so much that he soon altered it to Romero. At any rate, Ramon is a very interesting individual. When not making whoopee with the gang, he writes scenarios and plays, The Apache and Tropic Madness being examples of the former. His conversation is smart and entertaining. One of his prime ambitions is to have a stately home with the name Casa Nova brazenly topping the front gate. He would think of that.

Another conspicuous member of the gang is Marcel de Biraben, brother of Barry Norton. He came from the Argentine a few months ago as correspondent for several Buenos Aires newspapers. These two brothers and Paul Ellis, born Manuel Granado, are the only South Americans in the movie colony. Paul is a reserved and likable chap and, like most of the others, is trying desperately to discard his accent. Four out of five suffer from this! I must say that Hollywood will lose much of its color and spice, if it is ever recaptured by the Americans.

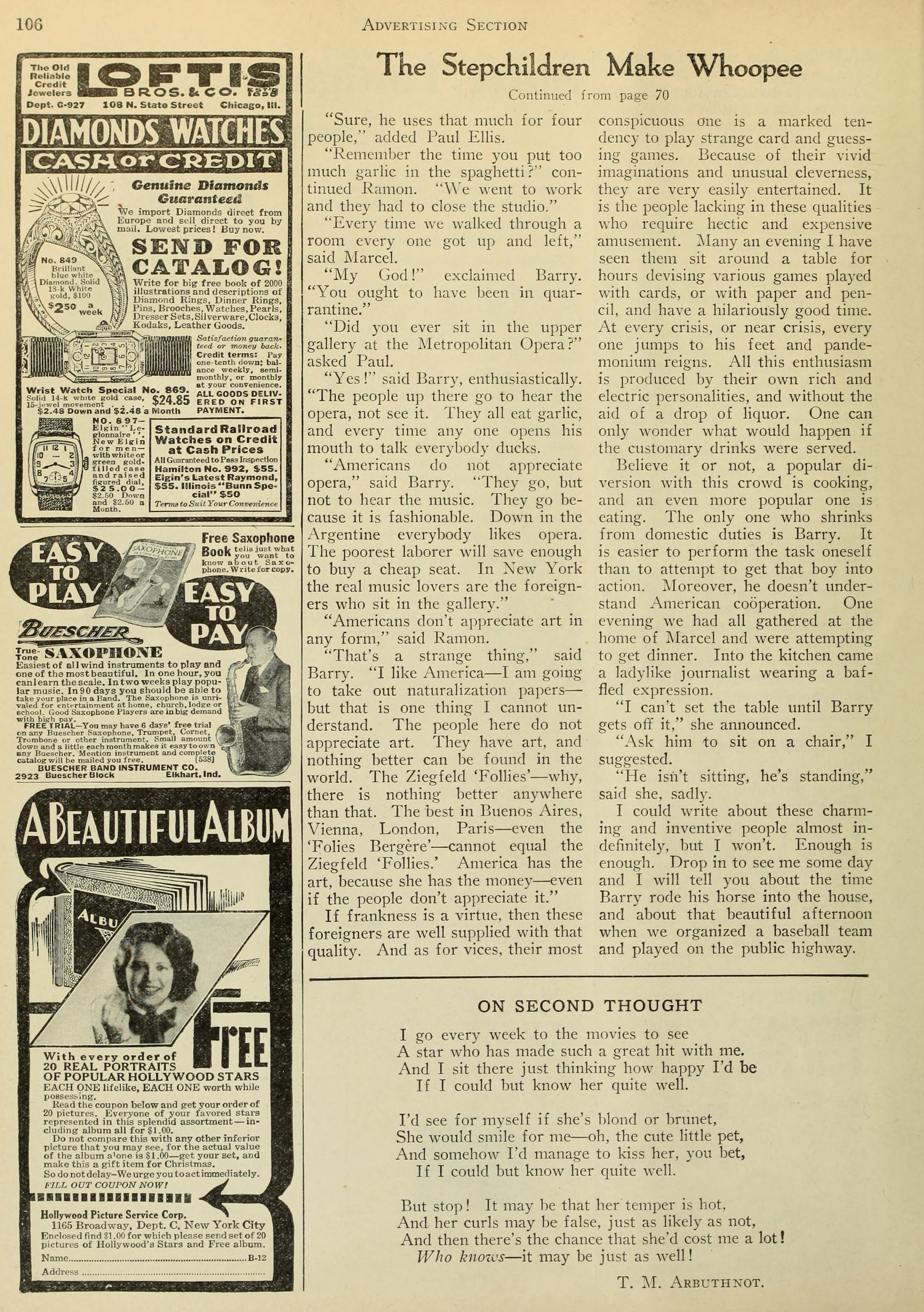

And then there is Gloria Gray, an ingénue of promise, whose success in the movies has been intermittent. She has been working steadily the past few months and, if given the right opportunity, she will score. Remember her as the heroine in “The Girl of the Limberlost.” Gloria is of the Alice White type, with thick, golden hair and immense, blue eyes. She plays the piano, rides splendidly, drives her own car, and cooks. Yes, cooks. I’ve seen her, and I’ve eaten the food she has prepared.

Recently at the home of one of the girls we enjoyed a spaghetti dinner which was cooked and served by members of the gang. The food was excellent, the diners at their gayest, and my only regret was that the conversation which flashed above that merry board could not have been recorded in shorthand.

“How much garlic did you put in this spaghetti?” asked Ramon of the chief cook.

“About twelve heads,” said Ruffo.

“You use more than that when you make it at my place,” remarked Ramon.

“Sure, he uses that much for four people,” added Paul Ellis.

“Remember the time you put too much garlic in the spaghetti?” continued Ramon. “We went to work and they had to close the studio.”

“Every time we walked through a room every one got up and left,” said Marcel.

“My God!” exclaimed Barry. “You ought to have been in quarantine.”

“Did you ever sit in the upper gallery at the Metropolitan Opera?” asked Paul.

“Yes!” said Barry, enthusiastically. “The people up there go to hear the opera, not see it. They all eat garlic, and every time any one opens his mouth to talk everybody ducks.

“Americans do not appreciate opera,” said Barry. “They go, but not to hear the music. They go because it is fashionable. Down in the Argentine everybody likes opera. The poorest laborer will save enough to buy a cheap seat. In New York the real music lovers are the foreigners who sit in the gallery.”

“Americans don’t appreciate art in any form,” said Ramon.

“That’s a strange thing,” said Barry. “I like America — I am going to take out naturalization papers — but that is one thing I cannot understand. The people here do not appreciate art. They have art, and nothing better can be found in the world. The Ziegfeld ‘Follies’ — why, there is nothing better anywhere than that. The best in Buenos Aires, Vienna, London, Paris — even the ‘Folies Bergère’ — cannot equal the Ziegfeld ‘Follies.’ America has the art, because she has the money — even if the people don’t appreciate it.”

If frankness is a virtue, then these foreigners are well supplied with that quality. And as for vices, their most conspicuous one is a marked tendency to play strange card and guessing games. Because of their vivid imaginations and unusual cleverness, they are very easily entertained. It is the people lacking in these qualities who require hectic and expensive amusement. Many an evening I have seen them sit around a table for hours devising various games played with cards, or with paper and pencil, and have a hilariously good time. At every crisis, or near crisis, every one jumps to his feet and pandemonium reigns. All this enthusiasm is produced by their own rich and electric personalities, and without the aid of a drop of liquor. One can only wonder what would happen if the customary drinks were served.

Believe it or not, a popular diversion with this crowd is cooking, and an even more popular one is eating. The only one who shrinks from domestic duties is Barry. It is easier to perform the task oneself than to attempt to get that boy into action. Moreover, he doesn’t understand American cooperation. One evening we had all gathered at the home of Marcel and were attempting to get dinner. Into the kitchen came a ladylike journalist wearing a baffled expression.

“I can’t set the table until Barry gets off it,” she announced.

“Ask him to sit on a chair,” I suggested.

“He isn’t sitting, he’s standing,” said she, sadly.

I could write about these charming and inventive people almost indefinitely, but I won’t. Enough is enough. Drop in to see me some day and I will tell you about the time Barry rode his horse into the house, and about that beautiful afternoon when we organized a baseball team and played on the public highway.

Lilya Vallon, actress, dancer and singer, is one of the lights in the little foreign circle.

Photo by: Russell Ball (1891–1942)

Ramon Romero, the scenarist, is a free spirit who indulges in gay suspenders and garlic.

Photo by: Preston Duncan (1899–1958)

Barry Norton, a leader in the group, says that America has art, but does not appreciate it.

Good cooking is the party gift of Gloria Gray, a promising ingenue during working hours.

Photo by: J. Anthony Bruno

Paul Ellis is a South American whose life is swept along between harmless whoopee and artistic pessimism.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, December 1929