Norman Taurog — He Was a Kid Himself! (1932) 🇺🇸

And he hasn’t forgotten it. That’s why Norman Taurog has achieved such wonders in directing child actors.

by Peter Long

Jackie Cooper was mad. Good and mad. He sought out uncle Norman Taurog on the set, and drew him to one side. Jackie is a normal little boy, and he has his mads and his sulks like any other little Skippy. In response to the director’s sympathy, the outraged Jackie confided:

“I don’t want to be President of the United States when I grow up!”

The man who won the Motion Picture Academy Award for directing the best picture of the year, Skippy, knows his kids. He became as indignant as Jackie. Some well-meaning assistant had told Jackie that if he didn’t do his work right that day, he would never grow up to be President.

“Don’t you worry, Jackie,” sympathized the director. “You don’t have to be President. Personally, I think you’re going to be the best baseball player in the world.”

Jackie’s eyes grew big with wonder. “Better ‘n Babe Ruth?” he asked. “Better’n Babe Ruth,” Taurog assured him loyally.

The rest of that day the little trouper worked like a trojan to play his scenes perfectly. Cried real tears and never dropped a line. Growing up to be a better baseball player than Babe Ruth is something to work for. Norman Taurog understands kid psychology.

Fortunate indeed is the man who never forgets that he was once a boy. Mark Twain never did. Neither have Booth Tarkington, Sir James M. Barrie, Percy Crosby and Norman Taurog. Twain, Tarkington and Barrie have made our childhood live again in books and plays; Crosby in cartoons and Taurog in motion pictures.

Of late Taurog has forsaken kid pictures for the more relaxing field of comedy. As a veteran of pictures he knows the grave danger of being typed.

“Besides,” explains Taurog, “I feel just as much at home directing Wheeler and Woolsey as I do Jackie Cooper. In temperament, kids are like comedians, and comedians are like kids. Big things seldom bother them; little things upset them terribly.

“If there is a difference it goes something like this: Jackie Cooper doesn’t want to be President of the United States, but both Wheeler and Woolsey have always wanted to be President!”

This wisecracking should definitely prove that Taurog is as much at home directing comedians as kids. But — getting back to the ten cardinal rules for directing children in pictures. After watching Taurog direct, plot, connive, cajole, manipulate, humor, coax, threaten, promise, soft-soap and act a part with such clever youngsters as Jackie Cooper, Mitzi Green, Jackie and Robert Coogan, Jackie Searl and Junior Durkin, I have come to the conclusion that making a real kid picture is the toughest job a man ever faced.

Garbo, Gable, Chatterton, Crawford, Bankhead and Barrymore have nothing on those six kids for individuality and temperament. What the kids lack in technique and understanding they make up in naturalness of emotions.

The director and I were sitting at ease on the set watching Jackie Cooper, Bobbie Coogan and Jackie Searl playing catch with their pals, the prop men and electricians. It was one of the frequent recess hours with which this wise and understanding man indulged his “children.”

“Let’s take your rule one,” I said. “Okay,” agreed the director, “look at each one of those three kids. As different as day and night. In many respects, they’re just as individual as the brilliant grown-ups. I study each child’s nature and disposition thoroughly before I attempt to use them in a picture. If those kids didn’t have ‘something’ they wouldn’t be so appealing and successful. Lacking maturity, children’s emotions are elemental. They can’t talk up — or talk back — to grown-ups who are telling them what to do. How then can one understand kids unless one is sufficiently interested and patient to penetrate the barrier of childish reticence? Boy, you’d be surprised at what you find out, and what they sometimes think of their grown-up bosses.”

I’ll bet. All parents reading this story might well ponder over Taurog’s words, because I know of no one who has made a more complete study of children.

“Naturally,” continued the director, “each youngster must be handled in a widely different way. For example: Jackie Cooper is Skippy. He’s a normal boy. He likes to boss his playmates if he can get away with it. That’s fine. Jack is a square-shooter, honest and loyal, and if he can hold down the head man’s job, it speaks well for his possibilities of becoming a real man when he grows up.

“I have always appealed to Jack’s sense of honor and fair play, when we don’t seem to be getting anywhere. Once when I had been held up on location, facing the loss of another day and a few thousand dollars in expense, I put it up to Jack. He and the rest of the kids were getting restless and I couldn’t get certain difficult scenes because of inattention. I appealed to Jackie’s sense of loyalty to the company and to me. I told him that if he would round up the other kids and get down to serious work, it would save my job. And I promised him a dollar!”

What in the world could a mere dollar mean to a youngster like Jackie Cooper who makes more money in one year than the President’s salary? I voiced my skepticism to the director.

Taurog laughed. “Why, man,” he said, “a dollar in the pocket means more to Jackie Cooper or any other kid than the vague thousands he hears he has in the bank. He understands a dollar. That will buy a lot of ice cream and candy, you know. Or, maybe a football or baseball.

“To get back to the location incident,” continued the director, “Jack rounded up the rest of the kids, including a score of Mexicans we were using for atmosphere, and we finished our final day’s work in record time. They paid strict attention and did everything right because Jack had put them on the spot, just as I put him on the spot.”

Here’s the pay-off. When Taurog returned to the studio he didn’t have the opportunity to give Jack the dollar. Next day when Taurog was sitting at an open office window conferring with Louis Lighten, the supervisor, they noticed the little man walking nonchalantly back and forth in front of the window. He was whistling and kicking his feet, boy-like. He was obviously trying not to be embarrassed, but he kept on strolling back and forth, whistling. Taurog let him go for a while. Finally, he had an assistant ask Jackie if he was looking for someone, or wanted something. Jackie hemmed and hawed and twisted. “Well,” he finally said, “Mr. Taurog promised me a dollar if I got all the kids to work hard and finish those scenes, but if there’s going to be a misunderstanding about it, it’s okay with me. I don’t mind losing that dime I had to give the kids. I’m working for the company.”

Of course, Jackie got the dollar. But, as Taurog put it, a grown-up would be highly commended for the same attitude. “He sure earned that dollar.” confided the director. “Rounding up all those other kids was a tougher job than those Borax wagon drivers used to have rounding up the twenty mules.”

Next in our confab came little Robert Coogan. Will he repeat the success of his “big brother” Jack?

“Bobbie is just a child now,” said Taurog. “He’s an affectionate little boy who must be handled solely by kindness. He isn’t old enough to reason out problems, so I had to find out how to occasionally overcome the inattentiveness of the child. Bobbie acts only for the praise of his pals, the stage-hands. If I can’t get Bobbie to play a scene right. I simply get one of the stage-hands to tell him that he’s not so hot. Or, if worst comes to worst, I’ll fire his best pal, the prop man. Kids do not like to be fooled. They resent it. So to make the threat good, I actually fire the prop man, send him home, and the next day I let Bobbie persuade me to hire his pal back again. Is he a good boy then!”

The more I talked to this director the more I came to realize why he made “Skippy” and “Sooky” and “Huckleberry Finn” and other real kid pictures.

Jackie Searl came under our observation next. Here is the kid “villain,” the youngster who is always running to tell “ma” or “pa” on the other kids. Why, I’ve heard folks coming out of theaters talking indignantly about that bratty kid.

“Jackie Searl is one of the nicest little boys imaginable,” the director assured me. “And what an actor. He’s as high-strung as a race horse, and as sensitive as a great artist. He can’t stand criticism, but neither can he stand the idea of others being made goats for his mistakes. So, when I bawl the other kids in a scene out for his mistake, he snaps out of it right away. He’s a sweet little fellow.”

Jackie Coogan, Mitzi Green and Junior Durkin are much more grown up, of course, but Taurog thinks they’re grand little troupers. All three are exceptionally conscientious in their work and can sometimes shame the grown-ups by being perfect “studies” in their lines. Some parents might readily take a few lessons from the infinite patience this director takes in handling his little charges. Picture what exhaustive consideration and genuine love of youngsters is necessary to achieve such results as were evidenced in “Skippy,” “Sooky,” and Taurog’s other kid pictures.

Win their confidence, discipline by kindness, and appeal to their sense of fair play, and you will get obedience and loyalty in return. Those are a few of Taurog’s rules we might all give heed to.

“I never show favoritism in handling Jackie Cooper, Bobbie Coogan, or Jackie Searl,” he says. “Although Jackie Cooper is my nephew, he has to toe the mark with me to get an even break. If I buy a baseball, or a toy auto, or an ice-cream cone for one, the other two get the same. Thus, their jealousy is never aroused. And one must never hurt their feelings by a mature indifference to their kid problems. I try to listen attentively and help them work things out.

“To break a promise to a youngster is not only cruel, but a fatal error. They never forget nor forgive deception of this sort.”

Picture theater-goers who wonder how the directors get such remarkable results from the screen children will be interested in this enlightenment. The youngsters are never over-worked. Every attention is paid to their health. Taurog frequently calls a recess hour during the working day when he sees his charges getting tired. After the relaxation of play they are back at it fresher than ever before.

Nor are results ever obtained by tricking or frightening the children. Taurog is contemptuous of such practices, which, it must be confessed, were used by some heedless picture-makers in the old silent days. Until wiser heads prevailed a few promising child careers were utterly ruined because the youngsters came to shy at a camera as a dog at a gun that had frightened it. Today, picture producers and directors must be commended for their painstaking care and treatment of the kid actors. They get better care and attention than do most kids at home.

Incidentally, the successful parents of these successful children are not the pestiferous kind that once infested Hollywood. They have common-sense. Mrs. Cooper, the Coogans, the Searls and others must be complimented for the conduct of their children.

Although Norman Taurog refuses to be caught in a cycle of kid pictures, because he happened to win the Motion Picture Academy Award for “Skippy,” he has a soft spot in his heart for the kids who rode along to fame with him. He would like to direct Barrie’s “Sentimental Tommy” and Tarkington’s “Seventeen” some time in the future.

Driving home the other evening from the studio I saw Norman Taurog playing baseball in a vacant lot in Beverly Hills with Jackie Cooper and some of Jackie’s small pals.

I’ll bet when Norman was a kid he was Skippy, too!

Norman Taurog’s Rules for Directing Children

- Study each child’s nature and disposition.

- Achieve discipline through kindness.

- Win the child’s confidence.

- Appeal to his sense of fair play.

- Never show favoritism or arouse jealousy.

- Don’t be indifferent to his problems.

- Never trick or frighten children.

- Don’t overwork them.

- Never break a promise to them. Kids do not forget.

- Don’t over-emphasize the importance of money.

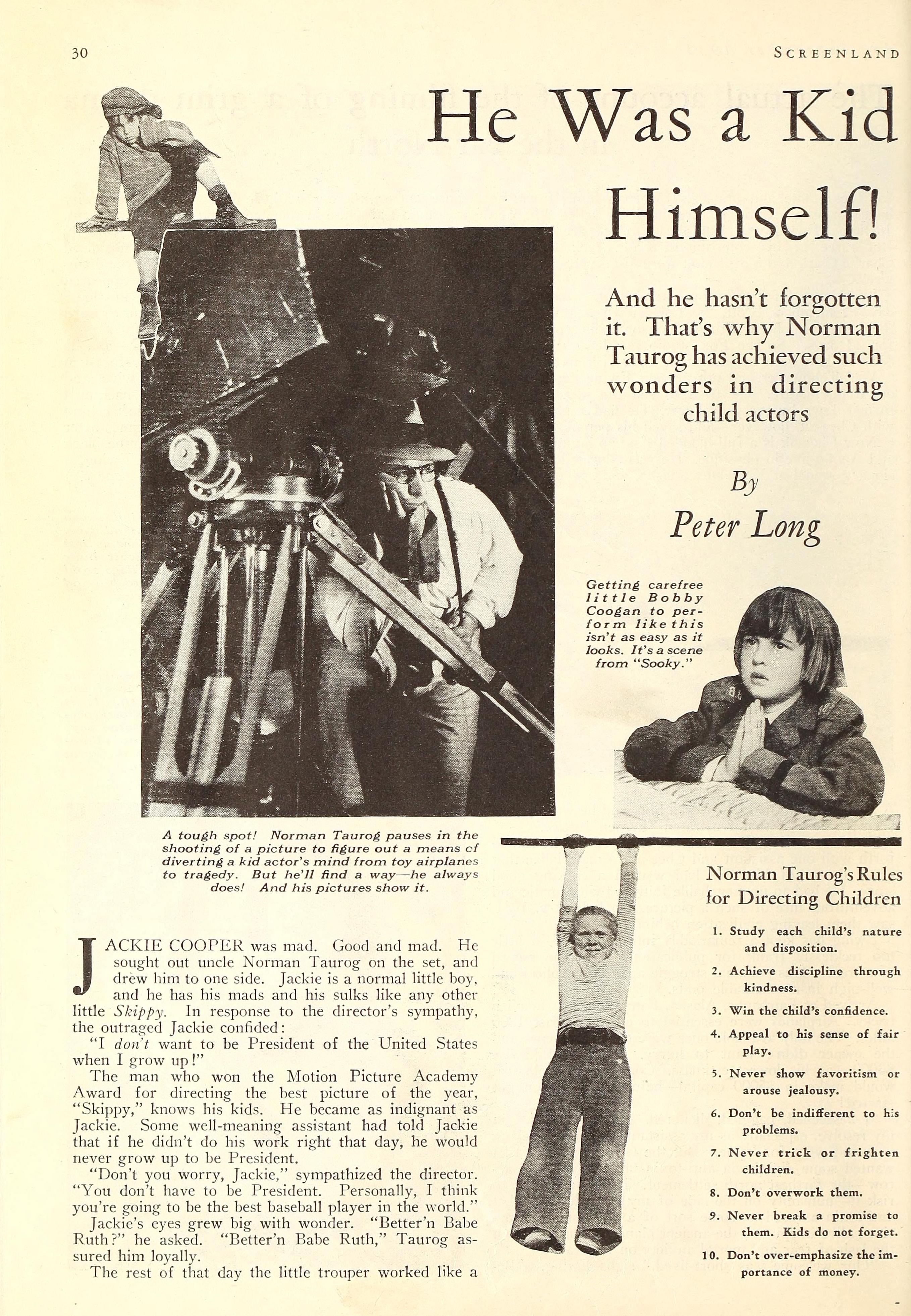

A tough spot! Norman Taurog pauses in the shooting of a picture to figure out a means of diverting a kid actor’s mind from toy airplanes to tragedy. But he’ll find a way — he always does! And his pictures show it.

Getting carefree little Bobby Coogan to perform like this isn’t as easy as it looks. It’s a scene from “Sooky.”

Even Jackie Cooper, the most finished of the diminutive stars, has his moments when he’d rather be smacking a baseball around than emoting before a camera. But Uncle Norman understands him — and that’s why “Skippy” was such a great picture.

Recess! Jackie Cooper (on opposite page) and Jackie Searl (left) need no encouragement to be themselves when play time is called on the set.

The captivating Coogans. Jackie’s grown up now, but still a swell actor. And you’ve seen what Bobby can do.

Movie crazy! That old funnybone tickler, Harold Lloyd, goes nuttier than ever in his new picture, which bears that name, and Constance Cummings helps along the general foolery.

Collection: Screenland Magazine, September 1932

---

see also this article from 1924 about Robert F. McGowan, the director of the early “Our Gang” shorts