Max Linder — Don’t Change Your Language (1921) 🇺🇸

Interviewing a foreign comedian proves many things to one; that one’s French vocabulary leaks like a sieve; that an interpreter is the better part of valor, and that if one thinks one speaks French, a few moments with a native of that so dear France disillusions one; it even makes one wonder what was the language they taught that passed for French in high school.

by Emma-Lindsay Squier

By this preamble you may know that I went, I saw, and that I was conquered. Of course, I knew that Max Linder was from Paris, and that he and the English language are scarcely on speaking terms, but what of that? Had I not wrestled for two years with la belle langue. Fraser and Squair’s grammar being the referee, and had I not emerged from the final round with an “A” for a grade, and a flock of irregular verbs harnessed meekly to my chariot wheels? Also, had I not read Cyrano de Bergerac in the original and bragged about it openly? I could even order meringue glace at dinner without a quiver, and once I said Bon jour to a French head waiter, who looked properly impressed. Why then, I ask you, should I have had any qualms about a mere interview with Max Linder? As I remember the details of the sad affair, I upstaged the interpreter who wanted to translate Max into English and me into French. I told him airily that I was quite proficient in French myself, oh, yes, quite!

Being a man, he took me at my word. Being a woman, I afterward resented it. He should have known!

Anyway, the place was Universal City, the time very slightly in the past, and the scene was a table in the cafeteria. The participants in the linguistic duel were Max Linder and myself. A sympathetic publicity man hung around the conversational outskirts, but he wasn’t much of a help. He thought pomme de terre was the French way of saying, “What’ll you have?”

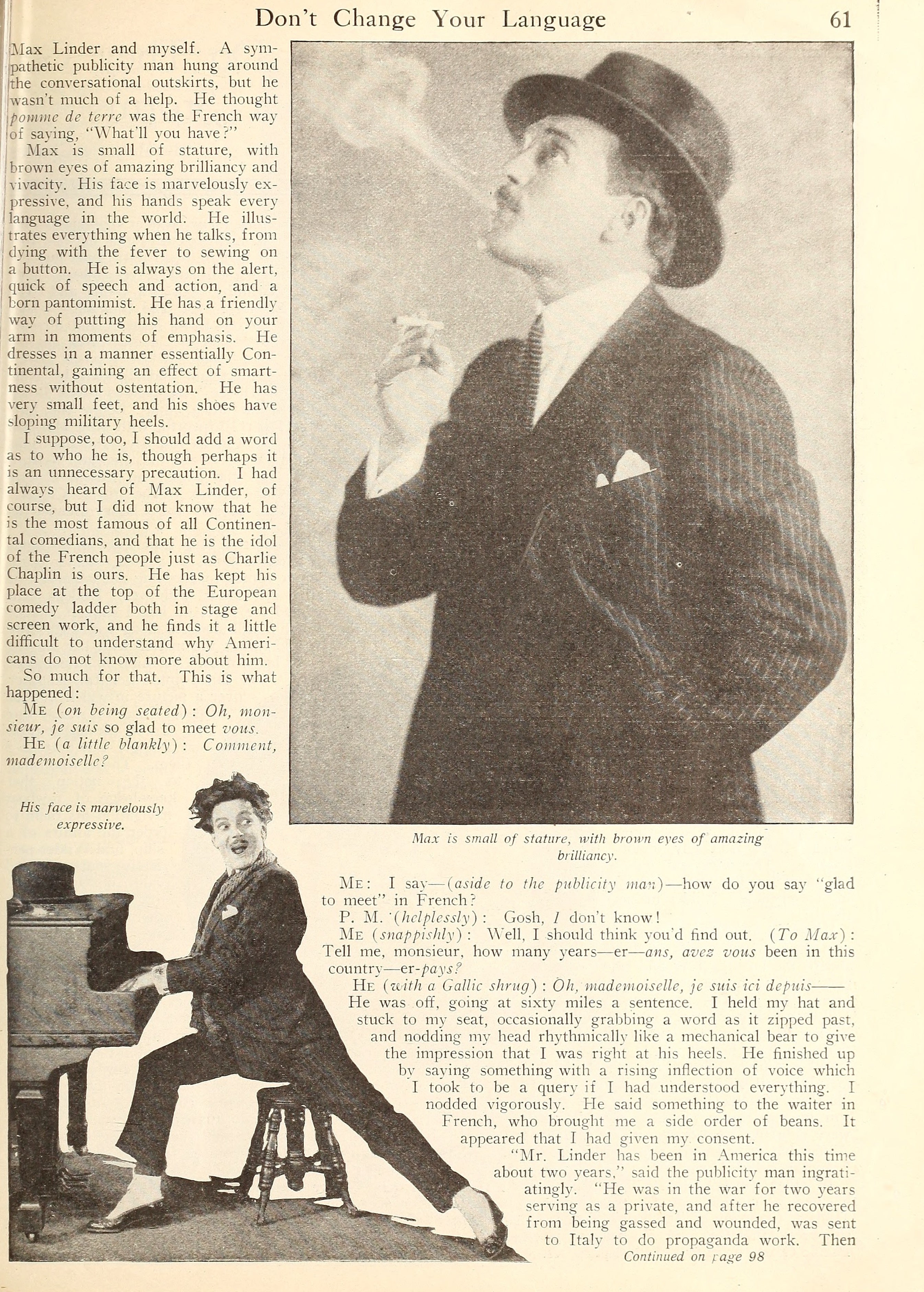

Max is small of stature, with brown eyes of amazing brilliancy and vivacity. His face is marvelously expressive, and his hands speak every language in the world. He illustrates everything when he talks, from dying with the fever to sewing on a button. He is always on the alert, quick of speech and action, and a born pantomimist. He has a friendly way of putting his hand on your arm in moments of emphasis. He dresses in a manner essentially Continental, gaining an effect of smartness without ostentation. He has very small feet, and his shoes have sloping military heels.

I suppose, too, I should add a word as to who he is, though perhaps it is an unnecessary precaution. I had always heard of Max Linder, of course, but I did not know that he is the most famous of all Continental comedians, and that he is the idol of the French people just as Charlie Chaplin is ours. He has kept his place at the top of the European comedy ladder both in stage and screen work, and he finds it a little difficult to understand why Americans do not know more about him.

So much for that. This is what happened:

Me (on being seated): Oh, monsieur, je suis so glad to meet vous.

He (a little blankly): Comment, mademoiselle?

Me: I say — (aside to the publicity man) — how do you say “glad to meet” in French?

P. M. (helplessly): Gosh, I don’t know!

Me (snappishly): Well. I should think you’d find out. (To Max): Tell me, monsieur, how many years — er — ans, avez vous been in this country — er — pays?

He (with a Gallic shrug): Oh, mademoiselle, je suis ici depuis —

He was off, going at sixty miles a sentence. I held my hat and stuck to my seat, occasionally grabbing a word as it zipped past, and nodding my head rhythmically like a mechanical bear to give the impression that I was right at his heels. He finished up by saying something with a rising inflection of voice which I took to be a query if I had understood everything. I nodded vigorously. He said something to the waiter in French, who brought me a side order of beans. It appeared that I had given my consent.

“Mr. Linder has been in America this time about two years,” said the publicity man ingratiatingly. “He was in the war for two years serving as a private, and after he recovered from being gassed and wounded, was sent to Italy to do propaganda work. Then he was released from service and came over here to make a picture that was called Max Comes Across. He went back to France for a while, but now he is over here on a two-year contract with Robertson-Cole to make eight comedies. He has finished Seven Years Bad Luck, and is now making his second picture, called Too Much Pep.”

I thanked him rather peevishly. I didn’t like the way he was smiling. Mr. Linder, whatever he may have felt, was disguising his feelings nobly. He even beamed upon me when I attempted a question in perfect high-school French as to how long he had been connected with pictures.

The publicity man groaned. Everyone in the world, it appeared, knew that but me.

“Oh, mademoiselle,” said Max, with his infectious smile, “I am what you say” — he thought deeply for a moment — “pioneer — in picture work. I commenced depuis dix-sept ans en Paris before Ie cinématographe was in I’Amérique.”

I nodded with sort of a set smile, and took refuge in my beans while I thought it over. After considerable digestion I arrived at the conclusion that Mr. Linder had worked in the movies seventeen years ago in Paris, considerably before America became infested by the noiseless drama.

“Oh, mon dew!” I said brightly. “How intéressant!”

“I made ze first — comprenez-vous — la première comédie zat was evair made, and we make one comédie a day. We work from nine in ze morning to four in ze afternoon, and zen — she was fineesh!”

I could see that he was storming the heights of the English language in an effort to reach my mental elevation. I tried desperately to ask what was the difference between the French and the American screen comedies, but only managed to make the word “risqué” intelligible.

The publicity man cocked his ear attentively. He recognized the adjective as something pertaining to lingerie farces.

‘‘Ze French screen comedies risqué?” repeated Max, his whole face expressing repugnance at the idea. “Oh, mademoiselle, non, non, je vous assure!”

He plunged passionately into a pounding surf of tangled verbs, allianced adjectives, and staccato expletives. His lamb chop cooled while he splashed in the monologue. I gathered that the French screen comedies were not risqué.

“Let me tell you,” he finished, emerging onto English sands, “in France zey would not permit Cecil De Mille to deesplay hees picture like Don’t Change Your Husband. On ze stage in France, ze risqué is all r-right; but on ze screen — oh, nevair, non, non!”

“Pourquaw pah?” I asked, having taken a moment to think up the way to say “Why not?” in French.

A series of shrugs, of voluble gesticulations, and enlightening facial expressions.

“Because, ze stage is expensive, n’est-ce pas? Only ze people who have plentee of money go. Alors, bien; zey have, how do you say —; deescrimination, zey are not effect by ze risqué. But ze screen is for children— for every one; comprenez-vous? Eet is necessaire to be veree careful. I never make a screen comédie which is risqué — jamais!”

The interpreter, who is also Max’s secretary came up just then, and from the conversation that followed, I gathered that the luncheon hour was long past, and that the cast were on the set awaiting Mr. Linder’s orders— for he directs as well as takes the lead in his comedies.

Max was lovely, and pretended that he had enjoyed the interview. I think Frenchmen are the most charming prevaricators in the world.

But the publicity man wasn’t so tactful. As I climbed into the machine which was to take me back to town, he bowed very low.

“Bon jour, mademoiselle,” he said in atrocious French, “come again, won’t vous?”

And I’m not ashamed to say that I stuck out my tongue at him. He was adding insult to my injury.

His face is marvelously expressive.

Max is small of stature, with brown eyes of amazing brilliancy.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, May 1921

---

see also Max Linder, the Inimitable (1910)