Lupe Velez — Just a Little Madcap (1929) 🇺🇸

The big talkie and sound men are exploiting Lupe Velez as another one of those pronoun girls, putting her up in the same tins as Alice White and Clara Bow, with a Mexican label to add a dash of chili, which is always good for the box office.

by Malcolm H. Oettinger

Lupe is one of nature’s children, playful, boisterous and as natural as a gullible fellow would be led to suspect.

When Lupe came to New York, advance word had it that the big town was in for a treat, so to speak. Here was everything from the Flame of Hollywood to the original Mexican jumping bean. This was the little girl who tore up Santa Monica Boulevard by the roots, addressed DeMille without saying “Please, sir,” and danced on tables as opportunity presented. She was alleged to be a lovable vixen, a madcap ingénue, a composite of Dolores del Rio, Olive Borden, Jetta Goudal, and Louise Fazenda.

Lupe, the ballyhoo intimated, had captured the hearts of many in very much the manner that Grant once took Richmond. The western world was at her little feet. It was all very moving. So, with a not unprecedented blast of trumpets, the tabasco baby wheeled into Broadway and Forty-Second Street. And Broadway managed to keep its head. There were no riots, no panics, and no more traffic jams than usual.

It was not altogether difficult to find her at the Rialto Theater, where she was making personal appearances at such odd moments as she was not trying on new frocks, feting the press, watching photographers’ birdies and radioing sweet nothings to her pooblic.

She popped into the room and registered the madcap stuff without wasting time.

“I steal things!” she announced. “I lot to steal things.”

That settled, she proceeded to point out on the table several incandescent bulbs “stolen” from the backstage lighting a floor below.

“Ever since a child, I lof to steal.” Lupe told me. “But I always give things back.” This was a reassuring touch.

She wore a simple, flowered dress, shoes with heels a shade higher than the Singer Building, and no stockings whatsoever.

It was difficult to commune with the Mexican flash, because she was busily trying on shoes which had been brought from a near-by Broadway shop. A patient salesman sat by and told her how well each shoe looked on the Velez foot.

“What the ‘ell!” exclaimed Lupe. “You try to choke me?” A shoe was tossed to the ceiling with a lusty kick. “That’s too damn tight! Aha, that’s betaire. That’s the bébé!”

So it went; pink shoes, brown boots, yellow and mauve. There were pert handbags to match.

“Griffith — ah, Lupe lof him. He great director. Yas, he was a fine man. Lupe lof him. Happy to work for him? Yas. Trouble with Goudal? Who have trouble? Lupe nevaire have trouble with any one. Unless she want to. Lupe nevaire give trouble. No fight. But when she fight — look out!”

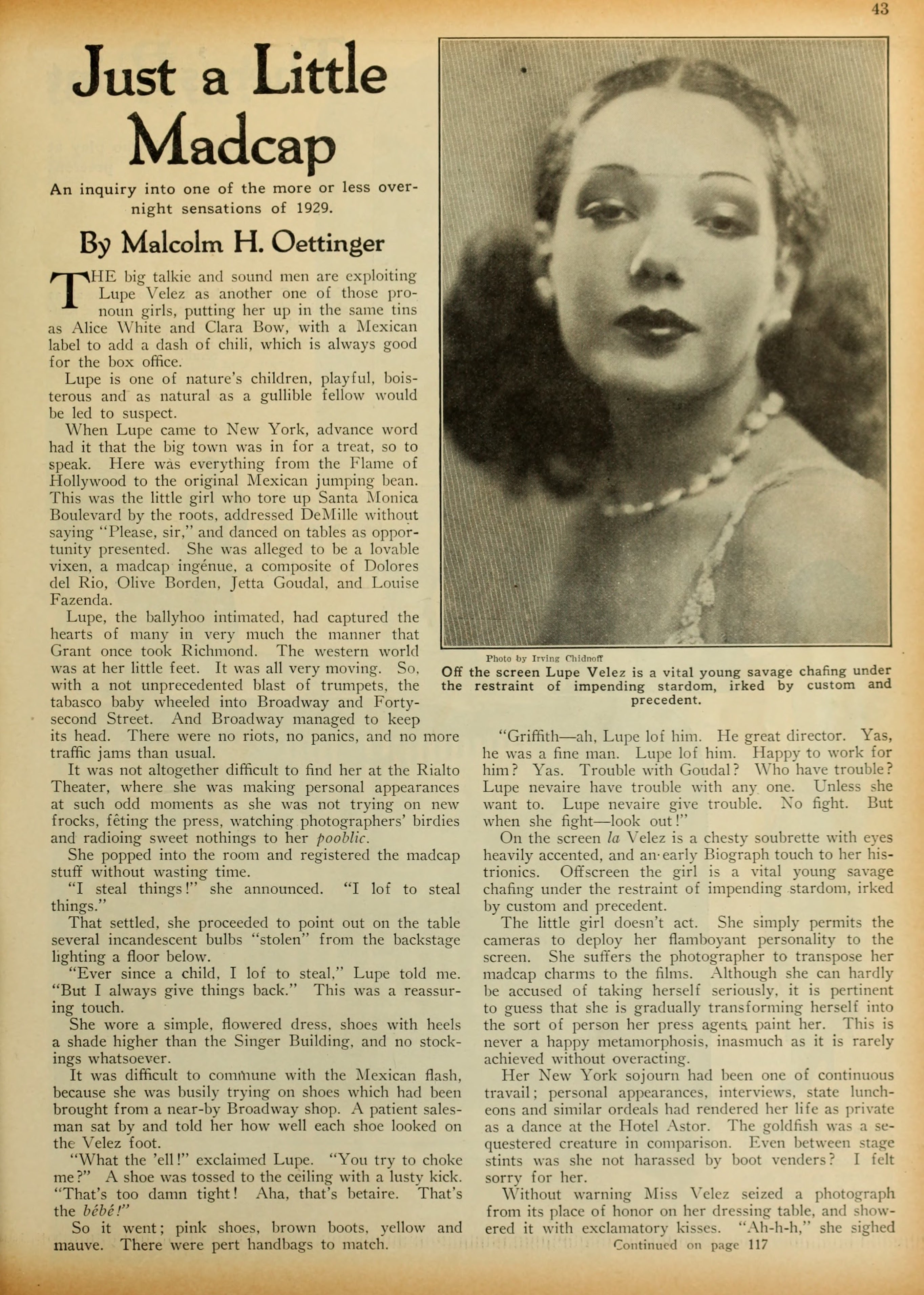

On the screen la Velez is a chesty soubrette with eyes heavily accented, and an- early Biograph touch to her histrionics. Offscreen the girl is a vital young savage chafing under the restraint of impending stardom, irked by custom and precedent.

The little girl doesn’t act. She simply permits the cameras to deploy her flamboyant personality to the screen. She suffers the photographer to transpose her madcap charms to the films. Although she can hardly be accused of taking herself seriously, it is pertinent to guess that she is gradually transforming herself into the sort of person her press agents paint her. This is never a happy metamorphosis, inasmuch as it is rarely achieved without overacting.

Her New York sojourn had been one of continuous travail: personal appearances, interviews, state luncheons and similar ordeals had rendered her life as private as a dance at the Hotel Astor. The goldfish was a sequestered creature in comparison. Even between stage stints was she not harassed by boot venders? I felt sorry for her.

Without warning Miss Velez seized a photograph from its place of honor on her dressing table, and showered it with exclamatory kisses. “Ah-h-h,” she sighed heatedly, “my Gicko; I lof him so! And soon I will see him again. In six, eight — how many days?” Straightway she brought to light a calendar, already covered with x’s that canceled the days past. “Six, seven — ah. eight!” she cried. “Eight more days and I will see my man!” I waited for the refrain, but in vain. Her man, she told me, with no little eloquence, played opposite her in “Wolf Song,” a picture one recalls as having no wolf and too much song, and from the first day they were, as Walter Winchell so aptly puts it, that way about each other.

Lupe was skyrocketed to prominence by the enthusiastic Fairbanks, for whom she acted up in “The Gaucho.” From that picture forward she was destined to be a spitfire.

D. W. Griffith took her in hand to add a touch of canned heat to his little opus called Lady of the Pavements, the theme song of which could happily have been Lady of the Pavements, I’d Walk a Mile for You!

Now Lupe is one of those United Artists, and rather inordinately proud of the idea. She speaks of herself as Lupe, flashes her eyes extravagantly, avoids the conventional in speech and posture, and registers gayety untrammeled at any cost.

She is sought after by advertisers who want her endorsement on suspension bridges, cyclone fencing, canary feed, health lamps, stainless-steel can openers and similar impressive products. She has made a phonograph record that plaintively inquires Where Is the Song of Songs for Me? and it may be dismissed with a gentle pat: and there have been numerous radio appearances during which Lupe has cried greetings to her dollinks and sweet pipple, all of which may or may not be good publicity. In any case Lupe has enjoyed a widespread campaign that has employed the deadliest weapons known to the crafty exploiteer.

“Joe Schenck [Joseph M. Schenck] has me under contract,” she said gayly. “I no give a damn how many mergers go. Lupe is set!”

By this time the patient shoe salesman had vanished with his mountain of boxes, the Velez eyes were heavy with kohl, the Velez lips were lavishly carmined, and belowstairs the orchestra was vamping till ready.

“Let’s go!” shouted the Mexican wild cat. “Lupe’s ready!” And the storm of applause greeting her entrance on the stage clearly demonstrated that the great American public knows precisely what it wants.

[b]

Off the screen Lupe Velez is a vital young savage chafing under restraint of impending stardom, irked by custom and precedent.

Photo by: Irving Chidnoff (1896–1966)

Ever since a child I lof to steal — but I always give things back,” said Lupe Velez to Malcolm H. Oettinger, whose story opposite reports a visit to the much-discussed Mexican girl in the excitement of her invasion of Broadway.

Photo by: Irving Chidnoff (1896–1966)

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, October 1929