Jack Holt — En Famille (1927) 🇺🇸

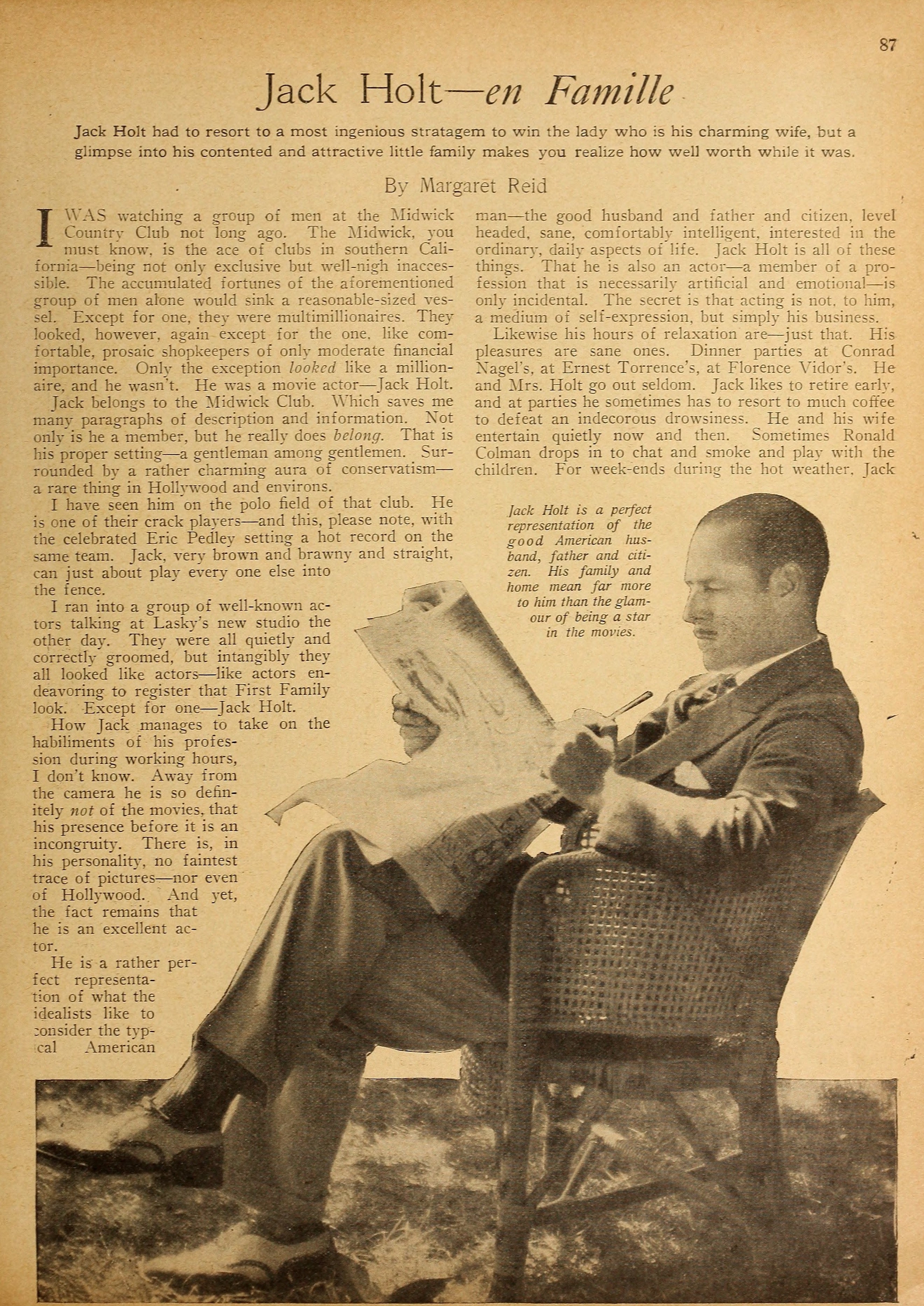

I was watching a group of men at the Midwick Country Club not long ago. The Midwick, you must know, is the ace of clubs in southern California — being not only exclusive but well-nigh inaccessible. The accumulated fortunes of the aforementioned group of men alone would sink a reasonable-sized vessel. Except for one, they were multimillionaires. They looked, however, again except for the one, like comfortable, prosaic shopkeepers of only moderate financial importance. Only the exception looked like a millionaire, and he wasn’t. He was a movie actor — Jack Holt.

by Margaret Reid

Jack belongs to the Midwick Club. Which saves me many paragraphs of description and information. Not only is he a member, but he really does belong. That is his proper setting — a gentleman among gentlemen. Surrounded by a rather charming aura of conservatism — a rare thing in Hollywood and environs.

I have seen him on the polo field of that club. He is one of their crack players — and this, please note, with the celebrated Eric Pedley setting a hot record on the same team. Jack, very brown and brawny and straight, can just about play every one else into the fence.

I ran into a group of well-known actors talking at Lasky’s [Jesse L. Lasky] new studio the other day. They were all quietly and correctly groomed, but intangibly they all looked like actors — like actors endeavoring to register that First Family look. Except for one — Jack Holt.

How Jack manages to take on the habiliments of his profession during working hours, I don’t know. Away from the camera he is so definitely not of the movies, that his presence before it is an incongruity. There is, in his personality, no faintest trace of pictures — nor even of Hollywood. And yet, the fact remains that he is an excellent actor.

He is a rather perfect representation of what the idealists like to consider the typical American man — the good husband and father and citizen, level headed, sane, comfortably intelligent, interested in the ordinary, daily aspects of life. Jack Holt is all of these things. That he is also an actor — a member of a profession that is necessarily artificial and emotional — is only incidental. The secret is that acting is not. to him, a medium of self-expression, but simply his business.

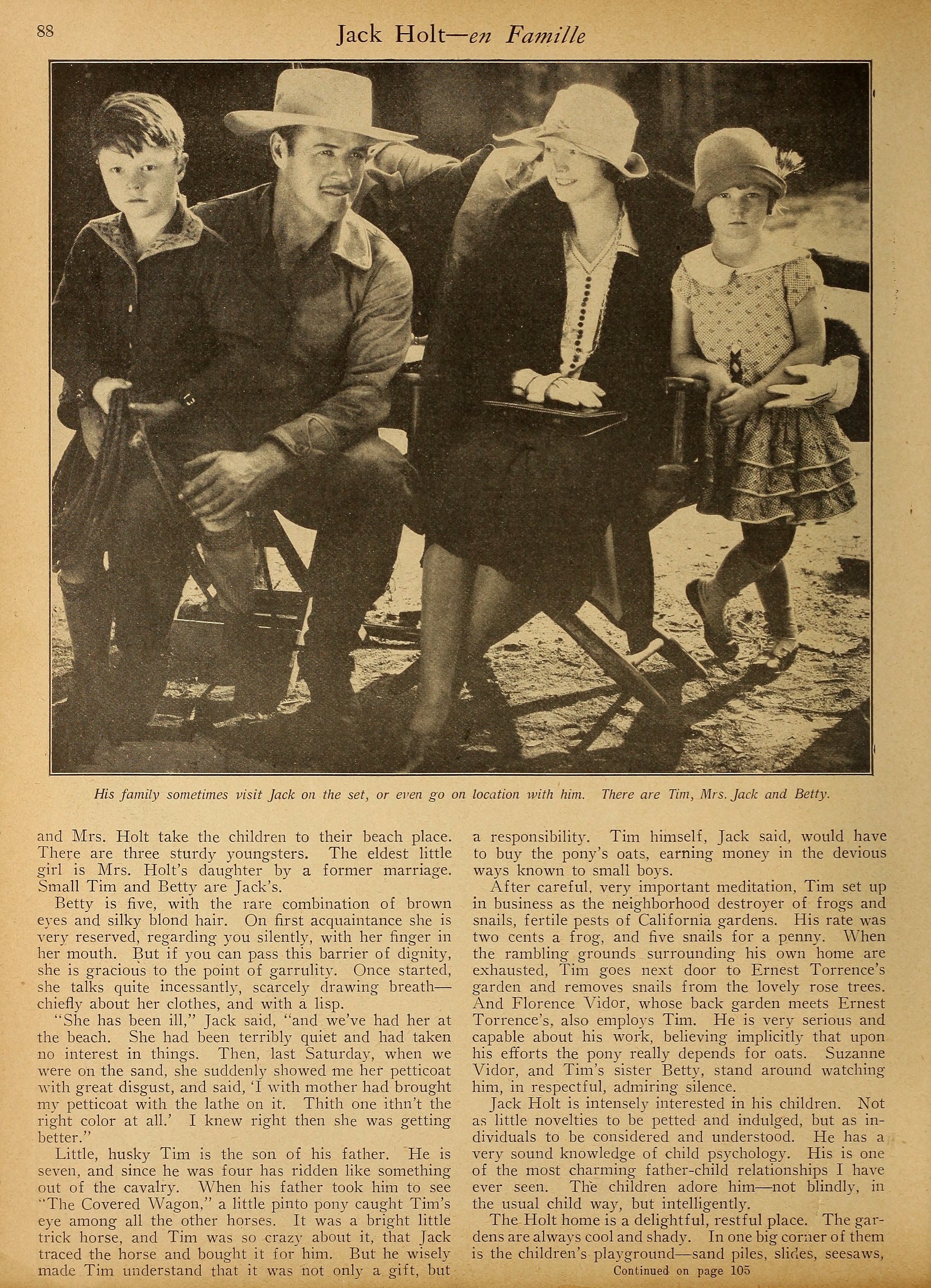

Likewise his hours of relaxation are — just that. His pleasures are sane ones. Dinner parties at Conrad Nagel’s, at Ernest Torrence’s, at Florence Vidor’s. He and Mrs. Holt go out seldom. Jack likes to retire early, and at parties he sometimes has to resort to much coffee to defeat an indecorous drowsiness. He and his wife entertain quietly now and then. Sometimes Ronald Colman drops in to chat and smoke and play with the children. For week-ends during the hot weather, Jack and Mrs. Holt take the children to their beach place. There are three sturdy youngsters. The eldest little girl is Mrs. Holt’s daughter by a former marriage. Small Tim and Betty are Jack’s.

Betty [Jennifer Holt] is five, with the rare combination of brown eyes and silky blond hair. On first acquaintance she is very reserved, regarding you silently, with her finger in her mouth. But if you can pass this barrier of dignity, she is gracious to the point of garrulity. Once started, she talks quite incessantly, scarcely drawing breath — chiefly about her clothes, and with a lisp.

“She has been ill,” Jack said, “and we’ve had her at the beach. She had been terribly quiet and had taken no interest in things. Then, last Saturday, when we were on the sand, she suddenly showed me her petticoat with great disgust, and said, ‘I with mother had brought my petticoat with the lathe on it. Thith one ithn’t the right color at all.’ I knew right then she was getting better.”

Little, husky Tim [Tim Holt] is the son of his father. He is seven, and since he was four has ridden like something out of the cavalry. When his father took him to see The Covered Wagon, a little pinto pony caught Tim’s eye among all the other horses. It was a bright little trick horse, and Tim was so crazy about it, that Jack traced the horse and bought it for him. But he wisely made Tim understand that it was not only a gift, but a responsibility. Tim himself, Jack said, would have to buy the pony’s oats, earning money in the devious ways known to small boys.

After careful, very important meditation, Tim set up in business as the neighborhood destroyer of frogs and snails, fertile pests of California gardens. His rate was two cents a frog, and five snails for a penny. When the rambling grounds surrounding his own home are exhausted, Tim goes next door to Ernest Torrence’s garden and removes snails from the lovely rose trees. And Florence Vidor, whose back garden meets Ernest Torrence’s, also employs Tim. He is very serious and capable about his work, believing implicitly that upon his efforts the pony really depends for oats. Suzanne Vidor, and Tim’s sister Betty, stand around watching him, in respectful, admiring silence.

Jack Holt is intensely interested in his children. Not as little novelties to be petted and indulged, but as individuals to be considered and understood. He has a very sound knowledge of child psychology. His is one of the most charming father-child relationships I have ever seen. The children adore him — not blindly, in the usual child way, but intelligently.

The Holt home is a delightful, restful place. The gardens are always cool and shady. In one big corner of them is the children’s playground — sand piles, slides, seesaws, and a detailed playhouse. There are dogs chasing each other through the hedges, and the flowers are not too jealously guarded from careless child hands and feet. Well back from the quiet street, the old-fashioned, sprawling, yellow-shingle house is set under pungent eucalyptus trees.

Mrs. Holt is a charming, cultured woman, removed from any touch of modern hysteria, and happy in her home and husband and children. The story of her romance with Jack is not very widely known. They first met when he was just beginning in pictures, doing heavies. She had come to California for the winter. They met, were mutually stricken, and would have married immediately had not Mrs. Holt’s very conservative father objected strenuously to admitting an actor into the family, and straightway carried her back to her New England home.

During the subsequent period of separation, their only means of communication was the screen. They devised a code. Jack wore a big signet ring and, in scenes where his hands registered prominently, he used to turn the ring — right, or left, or all the way round. Each twist had some particular message. Back in New England, the present Mrs. Holt used to watch for his pictures at the local theater and spend whole afternoons eagerly reading his messages over and over again.

And so, going from one thing to another, they were finally married. And stayed married, even in Hollywood.

Meantime, he continues to make pictures — the Westerns he enjoys so thoroughly. He likes the horses, the outdoors, the location trips. On location, Tim and Betty often accompany him. In Jack’s picture, Forlorn River. Tim played a little part, riding his own pony. His sense of importance was terrific, particularly at the end of each day when he received his salary of ten cents. He saved it all up and bought his father five brilliantly painted, tin ash trays in the Indian settlement. The prodigality of five ash trays at once appealed to him. Jack talks about his family with a sincere attempt at modesty. But it is rather hard to be modest about a family like his. The children. Mrs. Holt, their home, the horses — all the human things that go to make up his life — mean a thousand times more to Jack Holt than the ephemeral and questionable glamour of being a star in the movies.

—

Jack Holt is a perfect representation of the good American husband, father and citizen. His family and home mean far more to him than the glamour of being a star in the movies.

—

His family sometimes visit Jack on the set, or even go on location with him. There are Tim, Mrs. Jack and Betty.

—

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, May 1927