Glorian Swanson — Gloria with Reservations (1921) 🇺🇸

It was outrageous of me, of course. Luncheon with Gloria Swanson should have made me ecstatically unexacting. But it didn’t. I kept returning to the possibilities of deliberately spilling my ice cream. I wondered, madly, what would happen. I wondered if in that way I couldn’t make her start up, or exclaim, or do something impulsive. I wondered whether she had ever known the silly joy of giggling, or of sticking out her tongue at people. I thought furtively of what I might accomplish with a pin. Mentally, I was impossible. Actually I was concerned with the careful manipulation of my spoon and with timing my nods to the various things that Gloria was saying.

by Willis Goldbeck

We were in the dining room of the Beverly Hills Hotel. Gloria, her husband, and little Gloria occupy one of the several bungalows clustered in the grounds. Her husband was there, just across the table, apparently unconcerned over the stupendous miracle of being her husband, and there were two others, pleasant guests. They were all going over to the automobile races after lunch.

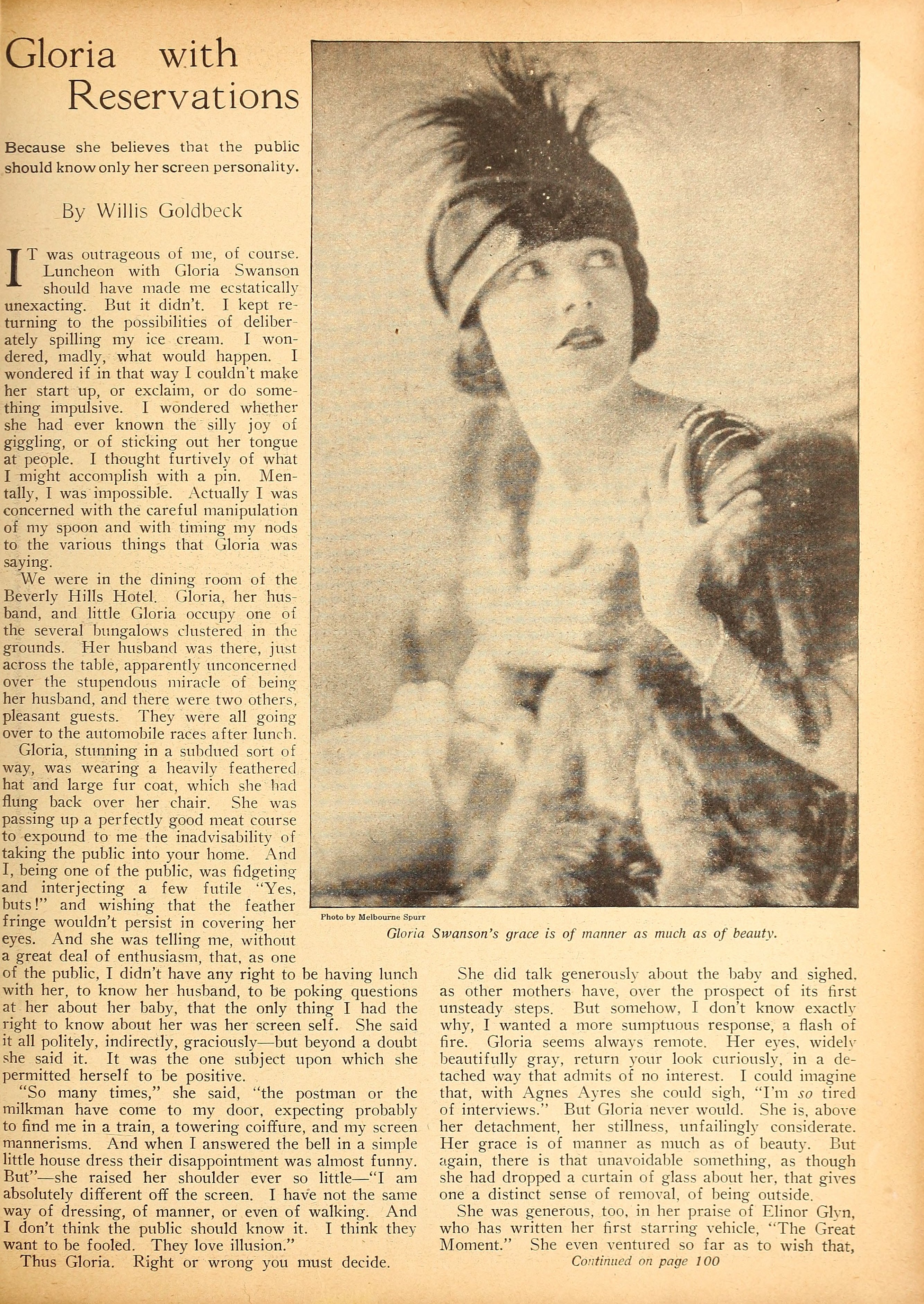

Gloria, stunning in a subdued sort of way, was wearing a heavily feathered hat and large fur coat, which she had flung back over her chair. She was passing up a perfectly good meat course to expound to me the inadvisability of taking the public into your home. And I, being one of the public, was fidgeting and interjecting a few futile “Yes, buts!” and wishing that the feather fringe wouldn’t persist in covering her eyes. And she was telling me, without a great deal of enthusiasm, that, as one of the public, I didn’t have any right to be having lunch with her, to know her husband, to be poking questions at her about her baby, that the only thing I had the right to know about her was her screen self. She said it all politely, indirectly, graciously — but beyond a doubt she said it. It was the one subject upon which she permitted herself to be positive.

“So many times,” she said, “the postman or the milkman have come to my door, expecting probably to find me in a train, a towering coiffure, and my screen mannerisms. And when I answered the bell in a simple little house dress their disappointment was almost funny. But” — she raised her shoulder ever so little — “I am absolutely different off the screen. I have not the same way of dressing, of manner, or even of walking. And I don’t think the public should know it. I think they want to be fooled. They love illusion.”

Thus Gloria. Right or wrong you must decide.

She did talk generously about the baby and sighed, as other mothers have, over the prospect of its first unsteady steps. But somehow, I don’t know exactly why, I wanted a more sumptuous response, a flash of fire. Gloria seems always remote. Her eyes, widely beautifully gray, return your look curiously, in a detached way that admits of no interest. I could imagine that, with Agnes Ayres she could sigh, “I’m so tired of interviews.” But Gloria never would. She is, above her detachment, her stillness, unfailingly considerate. Her grace is of manner as much as of beauty. But again, there is that unavoidable something, as though she had dropped a curtain of glass about her, that gives one a distinct sense of removal, of being outside.

She was generous, too, in her praise of Elinor Glyn, who has written her first starring vehicle, The Great Moment. She even ventured so far as to wish that, when she had attained the same age, she might be as clever, as brilliant; that she might be like her.

I looked at Gloria, the richness of her skin, the limpid gray of her eyes — and didn’t second her wish.

Somehow, though not strangely, our talk turned to the subject of C. B. DeMille. I suggested, with a smile, that she probably looked back on her days with him, from her present position, with little regret.

“Stardom!” She swept it aside with a gesture, a disdaining moue. “It is nothing! It means only increased responsibility. No indeed! Given the chance I would go back to Mr. DeMille in a moment. With him I have always some one to fight for me, to lift the burdens. Rather than miss my last chance to work with him I played in The Affairs of Anatol, six weeks after my baby was born.”

Speaking later of little Gloria she said: “Of my own volition I shall never place her in pictures. So long as she is still a child I hope she may never enter a studio. I have seen too many movie children!”

“But after that, when she grows to have a mind of her own?”

“Then,” said Gloria, “if she wishes to take up pictures she may. I shall put no obstacle in her path. I think that every one has the final right to his or her own life.”

I was reminded of the story of how DeMille had attempted to remodel Gloria’s nose when she first went to him. He had insisted upon an operation. Gloria had wept her refusal. Since then her nose, with its sweeping curve, has become world famous.

Word came in again that friends were waiting outside. Gloria bestirred herself to rise.

“I am sorry,” she said, “that we could not have met at the studio. Here I am so like every one else!” She smiled faintly, showing her white teeth. I felt that she was miles, courteous miles, away from me.

Gloria Swanson’s grace is of manner as much as of beauty.

Photo by: Melbourne Spurr (1888–1964)

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, June 1921

---