Gilbert Roland — Norma Talmadge’s New Leading Man (1927) 🇺🇸

An infuriated bull galloped across the arena and stood, head lowered, front feet apart, ready to make a rush at the torero. Picadors rode here and there. Banderilleros jumped all over the place. The banderillas they hurled flew hither and yon, some sticking into the bull’s neck, which did anything but pacify him. The matador, holding the muleta and sword, waited for the bull to charge.

by William H. McKegg

“If the bull holds his front feet apart that will close his shoulder blades,” it was explained to me, “and the matador won’t be able to pierce the sword to the heart.”

I shuddered, praying the bull would conduct himself as any well-mannered bull should if he wants to be killed, and would hold his front legs close together. Otherwise, if he persisted in being obstinate, I had visions of seeing the matador flung into the air and caught, on his return toward earth, on the horns of the bull. The fight was fast and furious.

“That,” said Gilbert Roland, the matador of the above scene, which he had enacted on the carpet of his apartment, “is how to kill a bull.”

“You don’t say?” My words, like myself, were faint. “Do you mind if I get a drink of water?” I weakly added.

Thirty minutes before, when I had entered the apartment, I had been prepared to hear a stereotyped story from Roland about having been chosen to play Armand to Norma Talmadge’s Camille. But instead of finding him full of excitement over this great event, I had found him wildly enthusiastic over something entirely different— bullfighting!

“Don’t you start soon on the picture?” I sputtered from the kitchen, swallowing a mouthful of water and hoping to divert my companion from the sport of sunny Spain.

“Next week, I think,” Gilbert carelessly called back as he fondly handled two gayly colored banderillas, the red-and-gold ribbon bindings of which scarcely hid the ugly darts that stuck out at each end. “Now when you see the bull rushing toward you “

He was off again! Exclamations were the only words I had a chance to utter, and before I could make another comment about Camille, I was once more flung into the arena.

That Gilbert Roland, whose entire thoughts should have been wrapped up in the great role he was getting, has a passion for bullfighting is only natural. His father used to be a well-known matador in Spain. From an early age Gilbert was taught by him the rudimentary technique of this highly diverting sport. A goat was used in place of a bull. Thus the fighter of the future often found himself sitting on the ground.

Since his earliest days, Roland has traveled with his parents to many places. From Spain across the ocean to Mexico. From the Argentine up to Chile and Peru. Finally his father met with an accident in the arena. He was gored by a bull. His left side has been paralysed ever since. And yet his son still wants to follow the same career! But if he has inherited a passion for bullfighting from his father, Gilbert has inherited a love for acting from his mother. The latter bequest he is realizing; the other he saves for the future.

“This,” he enthused, waving the two banderillas at me, “is life! It’s part of me — the procession, the stirring music, the vast sand-covered arena, the cheering crowds — I’ll never rest until I face a raging bull, waiting for him to charge.”

To which I replied, “Bosh!” Whereupon, the appointed Armand loomed over me, like a menacing god, and stormed. “It’s the truth! I’ve been brought up on bullfighting — it’s in my blood!”

“All right, all right,” I acknowledged. “But I wish you would hang those darts back on the wall.” And I heaved a sigh of relief when, with the greatest veneration, he at last did.

This Gilbert Roland is a very sensitive, high-strung fellow. Born in Mexico of Spanish parentage, he has the Latin’s love for color and beauty. He speaks with a slight accent, but it is not very evident. Occasionally, he goes about with that secret-sorrow look affected by so many cinema youths. At other times, he is very exultant. While talking of Spain, for instance, he walked eagerly about.

“This” — he pointed to a Sierra landscape — “is Spain. This”— he stopped by some clusters of multi-colored flowers — “is Spain. And this, too.” He tenderly regarded the painting of a young girl dressed in what I took to be a foreign costume. Who was she, I asked.

“Clara — Clara Bow,” came the surprised answer, “when she was about twelve.” And Clara, so I recognized, it was.

When Gilbert Roland first came to Hollywood, he went through the usual hardships. I was pleased he did not mention them until I asked to hear about them.

It is probable that many of you saw this young player in The Plastic Age, the story of wild college life made by Schulberg [B. P. Schulberg] before he entered the Lasky [Jesse L. Lasky] fortress. Reviewers spoke well of Roland’s work in that picture. Clara Bow and Donald Keith were the two other wild collegians. When Schulberg joined Paramount this youthful trio went with him. Clara immediately rose. The boys, somehow, stayed on earth.

“My dear boy,” Schulberg explained to the aggrieved Mr. Roland, “there just isn’t any part suitable for you right now — but don’t get discouraged.” So Gilbert, who would do anything Schulberg told him to do, for it was Schulberg who gave him his first chance in pictures, waited. And waited. But outside of giving him a not-very-palatable part with Bebe Daniels in The Campus Flirt, Paramount continued to do nothing with him.

So, after a year, Gilbert left the company and struck out on his own. He appeared in The Blonde Saint for First National. Then came another spell of waiting. And just when he had reached a state of the very blackest despair, he was chosen to play opposite Norma Talmadge in Camille.

The fact that he did not break out in rhapsodical outbursts about having been given the part may have been a blind to cover an inner excitement.

“You surely feel great, though, don’t you, to know you are having such a splendid break?” I asked as I left him, hoping to get at least one comment on Camille.

“Listen,” he replied, “I can’t say just what I think about it all. I only know it is my greatest chance so far.”

“Then you really do prefer pictures to bullfighting?” I urged.

“What!” Mr. Roland looked smitten. “I say, my boy, you don’t know what it means. You haven’t got the Spanish temperament. If they’d let me, I’d go into the arena to-morrow! The combat, the excitement, the bellowing, snorting beast charging down on you!”

Staggering out into the fresh air I wondered about this young anomaly. When he should have been raving about Camille, he was going crazy over bulls!

It doesn’t seem right, does it?

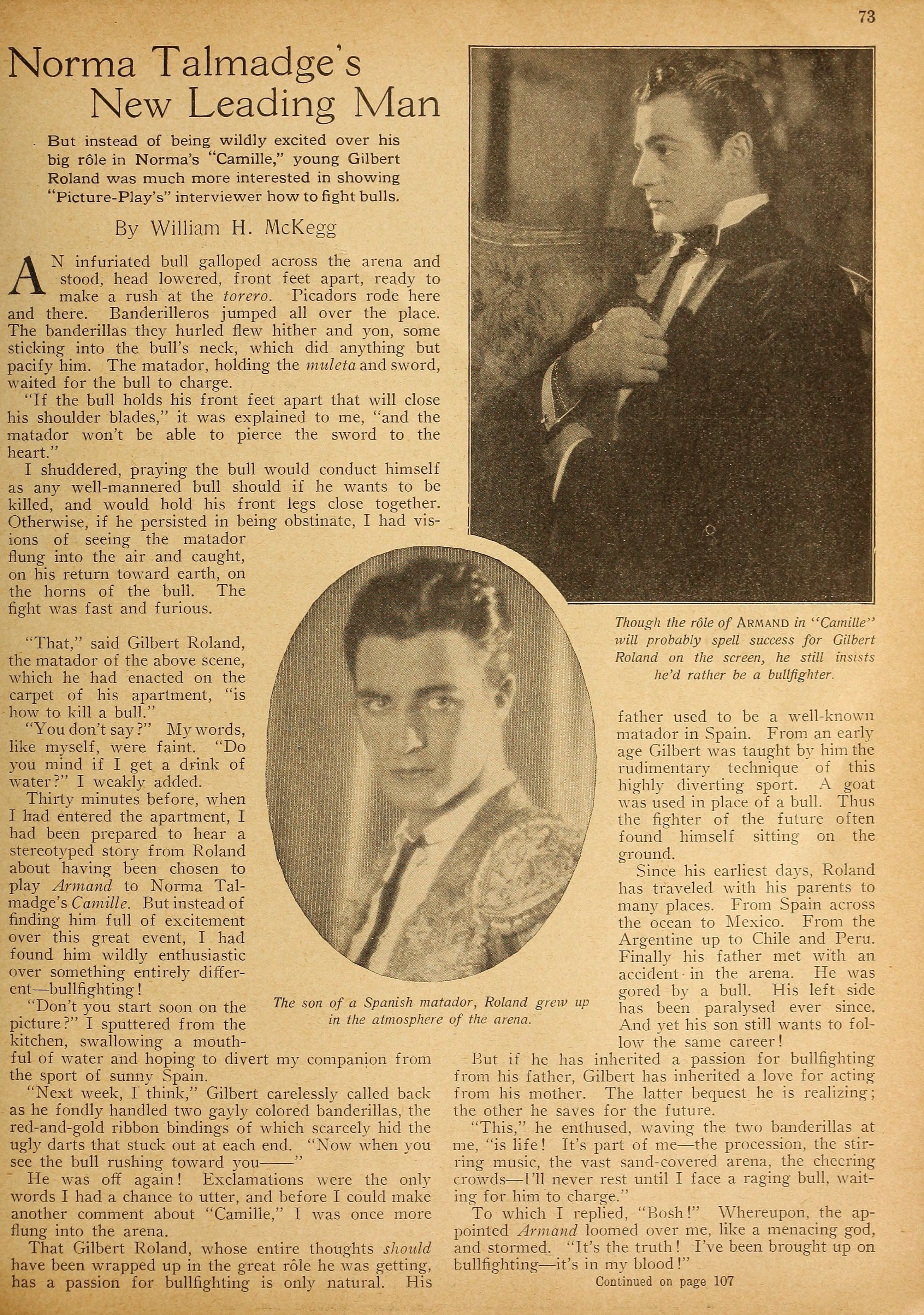

The son of a Spanish matador, Roland grew up in the atmosphere of the arena.

Though the role of Armand in Camille will probably spell success for Gilbert Roland on the screen, he still insists he’d rather be a bullfighter.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, April 1927