Conrad Veidt — A Welcome Invader from Germany (1927) 🇺🇸

It is seldom that you come across an actor who gets far enough from his screen self to seem an entirely different person in reality. There are, I don’t doubt, a few such, but very few. Conrad Veidt is one of the most amazing examples.

by William H. McKegg

Many of you already have seen Veidt on the screen, for several of his foreign pictures have been shown in this country. My first sight of this very remarkable actor was in The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, a picture applauded in New York for its striking originality and its freakish horrors. But owing to a wave of patriotic agitation, Caligari was not afforded the same notice and tolerance in other cities as was given it in cosmopolitan New York. Also, its ghostly horrors worried the censors.

Apart from the production itself, the greatest merits in this weird picture were the splendid performances given by Conrad Veidt as The Sleepwalker and by Werner Krauss as Doctor Caligari. Veidt looked like a living corpse, yet his make-up seemed in no way exaggerated. It was his sense of the part that created the effect.

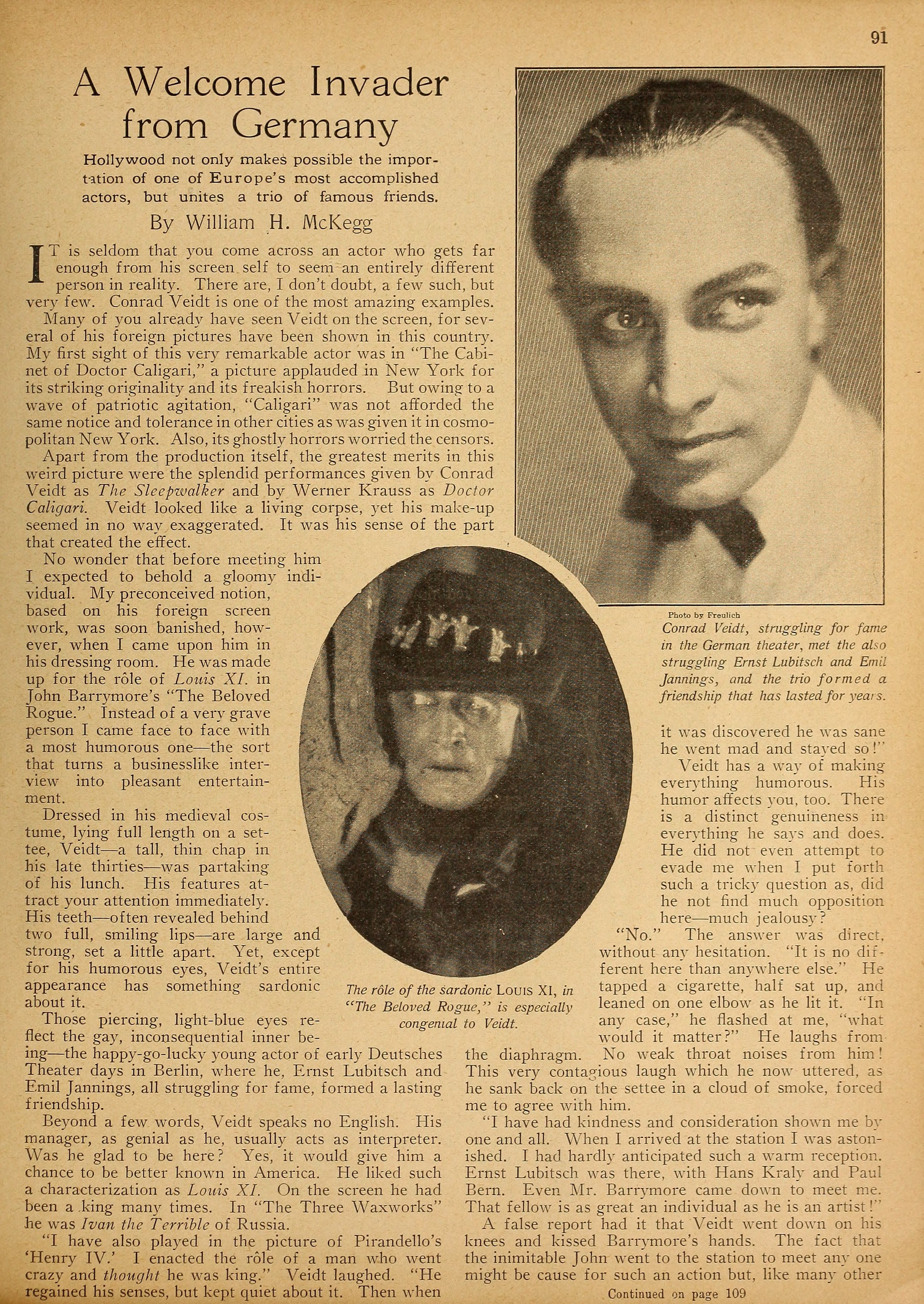

No wonder that before meeting him I expected to behold a gloomy individual. My preconceived notion, based on his foreign screen work, was soon banished, however, when I came upon him in his dressing room. He was made up for the role of Louis XI. in John Barrymore’s The Beloved Rogue. Instead of a very grave person I came face to face with a most humorous one — the sort that turns a businesslike interview into pleasant entertainment.

Dressed in his medieval costume, lying full length on a settee, Veidt — a tall, thin chap in his late thirties — was partaking of his lunch. His features attract your attention immediately. His teeth — often revealed behind two full, smiling lips — are large and strong, set a little apart. Yet, except for his humorous eyes, Veidt’s entire appearance has something sardonic about it.

Those piercing, light-blue eyes reflect the gay, inconsequential inner being — the happy-go-lucky young actor of early Deutsches Theater days in Berlin, where he, Ernst Lubitsch and Emil Jannings, all struggling for fame, formed a lasting friendship.

Beyond a few words, Veidt speaks no English. His manager, as genial as he, usually acts as interpreter. Was he glad to be here? Yes, it would give him a chance to be better known in America. He liked such a characterization as Louis XI. On the screen he had been a king many times. In The Three Waxworks he was Ivan the Terrible of Russia.

“I have also played in the picture of Pirandello’s Henry IV. I enacted the role of a man who went crazy and thought he was king.” Veidt laughed. “He regained his senses, but kept quiet about it. Then when it was discovered he was sane he went mad and stayed so!”

Veidt has a way of making everything humorous. His humor affects you, too. There is a distinct genuineness in everything he says and does. He did not even attempt to evade me when I put forth such a tricky question as, did he not find much opposition here — much jealousy? “No.” The answer was direct, without any hesitation. “It is no different here than anywhere else.” He tapped a cigarette, half sat up, and leaned on one elbow as he lit it. “In any case,” he flashed at me, “what would it matter?” He laughs from the diaphragm. No weak throat noises from him! This very contagious laugh which he now uttered, as he sank back on the settee in a cloud of smoke, forced me to agree with him.

“I have had kindness and consideration shown me by one and all. When I arrived at the station I was astonished. I had hardly anticipated such a warm reception. Ernst Lubitsch was there, with Hans Kraly [Hanns Kräly] and Paul Bern. Even Mr. Barrymore came down to meet me. That fellow is as great an individual as he is an artist!” A false report had it that Veidt went down on his knees and kissed Barrymore’s hands. The fact that the inimitable John went to the station to meet any one might be cause for such an action but, like many other things in the picture colony, the tale of Veidt’s genuflection was a gross exaggeration. What really happened was this: as he stepped off the train Veidt did kiss the hand of a lady he knew. So Barrymore, in facetious pantomime, kissed Veidt’s hand. Veidt, who recognized a fellow spirit of humor, capped the climax by kissing John on the cheek. And that is all there was to the kissing episode.

Some fifteen years ago, Max Reinhardt, the great producer, put on a production of Faust at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin. If you had told any one in the audience that the young player standing in the wings, intently watching every gesture made by the more experienced actors, was called Conrad Veidt, it would not have aroused the slightest interest. He was only a supernumerary.

Neither would the fact that his young friend, playing the very insignificant part of Famulus, was called Ernst Lubitsch have caused any demonstration of feeling. In fact, just a year before, Lubitsch had been just one of a mob of two thousand in Reinhardt’s London production of The Miracle.

Lubitsch, Veidt, and Emil Jannings have been great friends ever since those early struggles together. Each possesses an unconquerable sense of humor. Lubitsch was the first to come to America. Veidt and Jannings went on making pictures in Berlin. Jannings’ films were more fortunate in being shown in America than Veidt’s. Except for his roles in Doctor Caligari and Lord Nelson (Lady Hamilton (1921)), Veidt remained unknown to [Text Missing] fore, when Jannings received an offer to come over here and make pictures for Paramount, that Veidt was to be left behind. But before Jannings had had time to pack up and set sail, Veidt was invited by Barrymore to come to Hollywood to play in The Beloved Rogue.

When I saw him he was just completing his work in that picture. The week following, he told me, he was returning to Germany for a brief period and then would come back to America, for he had just signed a five-year contract with Universal. From now on he will probably divide his time between Hollywood and Berlin, making pictures in both cities.

His first for Universal is the film version of Victor Hugo’s The Man Who Laughs.

One of Veidt’s best characterizations was in a recent German production, The Brothers Schellenberg, which may or may not come to America.

We need not worry, however, about not seeing Conrad Veidt’s foreign pictures. His performance in his first American one is comparable to any of his previous work. Bear in mind, though, that however gruesome the role you may see Veidt play, he is not like that away from the screen. His breezy, humorous personality is the exact antithesis of the mood he usually assumes on the screen.

“When I return to California,” Conrad impressed on me at parting, “I shall have my wife and little baby with me.”

Now that he has returned, there isn’t a happier husband and father [Text Missing]

The role of the sardonic Louis XI, in The Beloved Rogue, is especially congenial to Veidt.

Conrad Veidt, struggling for fame in the German theater, met the also struggling Ernst Lubitsch and Emil Jannings, and the trio formed a friendship that has lasted for years.

Photo by: Roman Freulich (1898–1974)

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, 1927