Charles Morton — Laughing It Off (1929) 🇺🇸

Because Charles Morton had had a knock in the right eye, he was forced to delay our meeting. Charlie seems to get the knocks both figuratively and literally. An unpleasant position for any chap to be in — especially in Hollywood.

by William H. McKegg

As an introduction to the film colony, young Mr. Morton sprang into print by arousing the hectic passions of his wife. Something he had done annoyed her, and she threw scalding water in his face.

This uncomfortable notoriety was not very good for Charlie. In the first place, no one had known he was married. People talked, as they usually do about such surprising revelations.

After the storm had subsided, things went along again, Mr. Morton looking Hollywood squarely in the face, still smiling.

“That chap hasn’t a trouble in the world,” I told myself every time I saw his beaming countenance on the Fox lot. “There’s no Hollywood background in his life.”

In Four Sons he struck me as being something of an actor. His role of the blacksmith son was small. He came and went, as it were. But he was the only one who showed deep feeling while Margaret Mann, as the mother, blessed her two boys before they left for the front. Though Francis X. Bushman, Jr., looked pathetic, Mr. Morton allowed genuine tears to flood his eyes — a proof of histrionic ability, I concluded, and promised myself that as soon as he had done a few bigger things, he should be interviewed and given a chance to unburden himself to his public.

Soon after that, the scalding episode occurred.

It threw things out of focus a bit. An ever-smiling chap, who let real tears creep into his eyes while being blessed by a screen mother, seemed incongruous when mixed up with turbulent passions running to primitive encounters.

Did he, in spite of his seeming pathos, possess a Hollywood background?

Quite recently I found myself climbing a steep hillside stairway leading to Mr. Morton’s abode. Reaching a front door, which had no bell, I rapped once or twice.

A man in a dressing gown and pajamas opened it wide, without saying a word, as if he had been expecting me. He wore a bored expression, as though rapping on the door was an hourly occurrence. He was elderly enough to be Mr. Morton’s father, so I walked in. A matronly woman came, smiling, which almost suggested that she was expecting my visit, but desired me first to state my purpose. I asked for Mr. Charles Morton.

The woman threw a swift glance at the man in pajamas who, without a word, hastily flung open the door again — this time to let me out — his dressing gown billowed open by the breeze.

“Mr. Morton lives upstairs,” the woman assured me quickly. “Go round to the side, and walk up the steps.”

The door without a bell slammed. I sought the stairway.

Standing almost on the top step was a foreign gentleman, about forty. I recognized him as Charlie’s major-domo, Boris, for I had seen him driving the Morton car.

“Yes, sir. Step in, please.” I walked through an open window. “Mr. Morton will be in directly.” And the well-mannered Russian left to call him — though I had the impression that Charlie had just slipped out of the room. An actor must always have an “entrance.”

A radio was transmitting the tail-end of ‘an excerpt from Rimsky-Korsakow’s Scheherazade, the repeated motif of the first violins being full of horrible suggestions. Surely the wrong music to be flowing into the abode of an ever-smiling, young chap.

The furniture, too, seemed out of place for the bright Morton personality, as were also the plaster walls of the room. They were painted a gold color, with blue, pink, violet, and red spreading over them in streaks.

From the large studio window I could see all Hollywood and Los Angeles far below. I also noticed a young man mounting the hillside steps, evidently the visitor expected in the apartment beneath.

But panoramic views and mysterious visitors had to be disregarded for the moment, for Mr. Morton himself stepped briskly into the room, in shirt and trousers, a black shade over his right eye giving him the appearance of a good-looking pirate. He walks like a sailor, too, as a matter of fact.

“I got this playing handball at the Athletic Club,” he explained right away, fingering the shade. “For the past ten days I’ve had to stay in a darkened room.”

It seemed to me that Mr. Morton was slightly uneasy at my prying visit, as though some one had warned him to be careful. But of what? He appeared to be pondering over how much I knew, and how much he should tell. Suddenly he decided to become talkative. Perhaps that was because he had not seen any outsider fof ten days. Be that as it may, Charlie, before I knew it, was talking about his first facial mishap.

“You see,” he said, “I was married, and my wife got very jealous of me. You know how girls are out here — you know how they run after any chap who gets a break in the movies. My wife, a Spanish girl, was mad about something, and thought she’d fix me.

“I didn’t know what to do at the time. I had just begun work in ‘The Four Devils.’ Other scenes had to be shot while my face healed. Luckily no scars were left.

“No,” he repeated, “I didn’t know what to do. But I went around the studio as usual, smiling as I always do, so that no one would know how I really felt over it. I wanted them to see me as they always do — smiling. I think that’s the best way to take any misfortune.”

The divorce, which I was informed was granted, must have been conducted with the best of feelings between husband and wife; for several times I have caught a glimpse of Charlie and Lola, his fiery Spanish love, driving along the Boulevard. Maybe Charlie saw best to use his smiling philosophy.

Of interesting things his life is by no means the least.

He was one of those “dressing-room trunk babies.” His father and mother have been on the stage all their lives — both here and in Europe. His mother used to sing in Gilbert and Sullivan operas. Charlie makes his love for his parents very evident during his talk about them.

“My father and mother and brother, and Boris here, are my only real friends,” he confessed.

Born in Vallejo, California, he has traveled all over the country with theatrical companies. He was brought up and educated after a fashion in the theater, along with his brother.

“From fourteen to eighteen I went to high school — all the schooling I’ve ever had! And I actually graduated!” he added, with a smiling flourish. “I did extra work in New York.”

While doing that and playing in vaudeville and stock, Charlie — or Carl, as he was then called — met an agent, Jess Smith. Mr. Smith is evidently farseeing where talent is concerned. He urged Charlie to pack up and go out to Hollywood — alone.

I should state, perhaps, that Charlie was by this time married. He must have been bound in wedlock since he was seventeen or eighteen. He’s said to be only twenty-two now. It is hard to believe that he has ever been burdened with the responsibilities of marriage, for he is rather irresponsible and easy-going — always laughing.

Nevertheless, he came out to Hollywood alone, via the Panama Canal.

Mr. Smith came by train, to make “The Poor Nut.” The picture was made, but without Mr. Morton. Scouting around, Mr. Smith sent Charlie over to Fox to apply for a role.

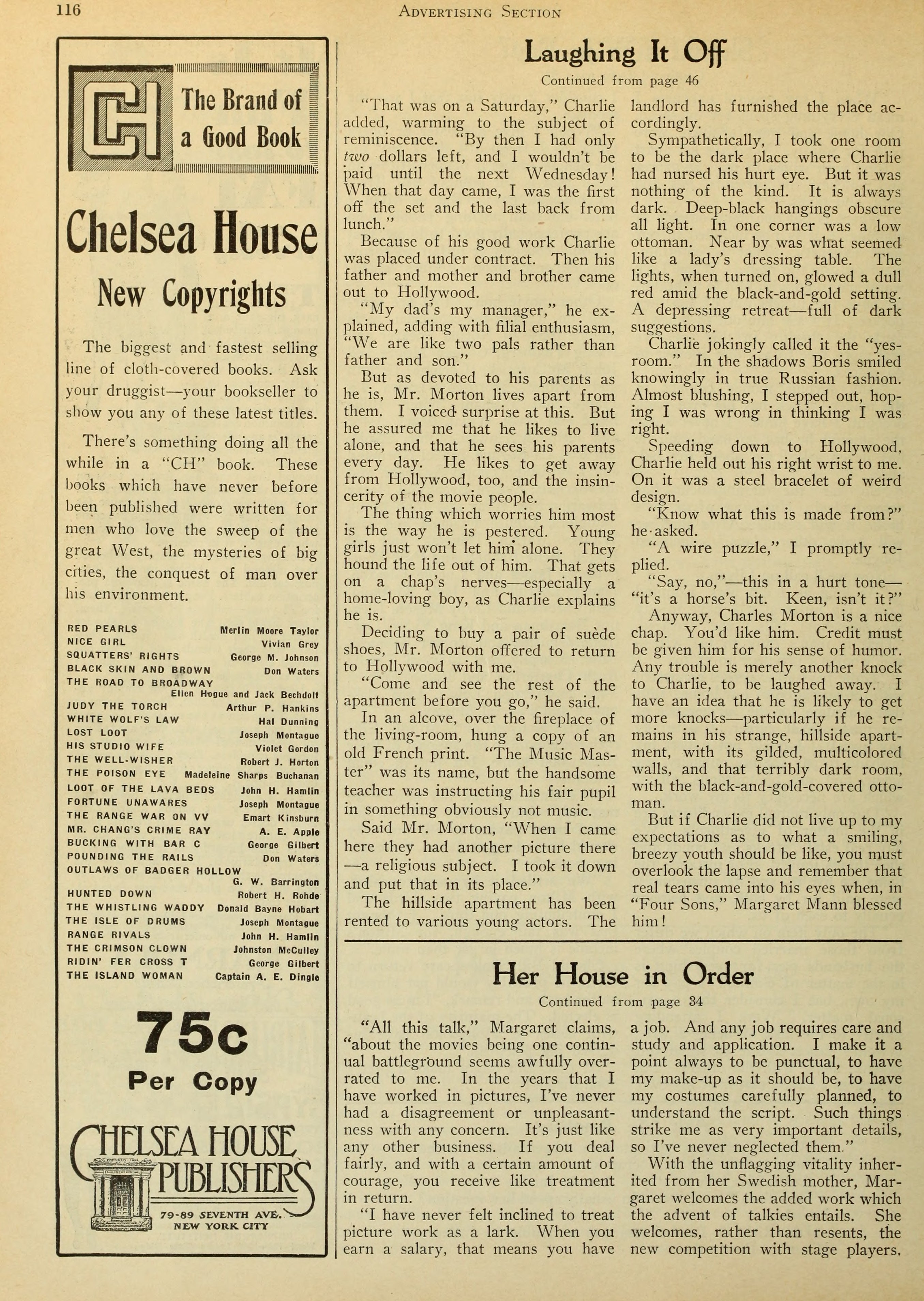

“They want a young chap with a smiling personality,” the agent said.

“You know,” Charlie, beaming, continued, “I had only three dollars left, and I went over to the studio in a taxi! That’s me. I always do something crazy like that.

“As a young chap with a smiling personality was needed, I intended to supply him. So I kept smiling at every one in the casting office, until I’m sure kinks came into my face!”

In brief, he was immediately signed for a lead in “Rich But Honest.”

“That was on a Saturday,” Charlie added, warming to the subject of reminiscence. “By then I had only two dollars left, and I wouldn’t be paid until the next Wednesday! When that day came, I was the first off the set and the last back from lunch.”

Because of his good work Charlie was placed under contract. Then his father and mother and brother came out to Hollywood.

“My dad’s my manager,” he explained, adding with filial enthusiasm, “We are like two pals rather than father and son.”

But as devoted to his parents as he is, Mr. Morton lives apart from them. I voiced- surprise at this. But he assured me that he likes to live alone, and that he sees his parents every day. He likes to get away from Hollywood, too, and the insincerity of the movie people.

The thing which worries him most is the way he is pestered. Young girls just won’t let him alone. They hound the life out of him. That gets on a chap’s nerves — especially a home-loving boy, as Charlie explains he is.

Deciding to buy a pair of suede shoes, Mr. Morton offered to return to Hollywood with me.

“Come and see the rest of the apartment before you go,” he said.

In an alcove, over the fireplace of the living-room, hung a copy of an old French print. “The Music Master” was its name, but the handsome teacher was instructing his fair pupil in something obviously not music.

Said Mr. Morton, “When I came here they had another picture there — a religious subject. I took it down and put that in its place.”

The hillside apartment has been rented to various young actors. The landlord has furnished the place accordingly.

Sympathetically, I took one room to be the dark place where Charlie had nursed his hurt eye. But it was nothing of the kind. It is always dark. Deep-black hangings obscure all light. In one corner was a low ottoman. Near by was what seemed like a lady’s dressing table. The lights, when turned on, glowed a dull red amid the black-and-gold setting. A depressing retreat — full of dark suggestions.

Charlie jokingly called it the “yes-room.” In the shadows Boris smiled knowingly in true Russian fashion. Almost blushing, I stepped out, hoping I was wrong in thinking I was right.

Speeding down to Hollywood, Charlie held out his right wrist to me. On it was a steel bracelet of weird design.

“Know what this is made from?” he asked.

“A wire puzzle,” I promptly replied.

“Say, no,” — this in a hurt tone — “it’s a horse’s bit. Keen, isn’t it?”

Anyway, Charles Morton is a nice chap. You’d like him. Credit must be given him for his sense of humor. Any trouble is merely another knock to Charlie, to be laughed away. I have an idea that he is likely to get more knocks — particularly if he remains in his strange, hillside apartment, with its gilded, multicolored walls, and that terribly dark room, with the black-and-gold-covered ottoman.

But if Charlie did not live up to my expectations as to what a smiling, breezy youth should be like, you must overlook the lapse and remember that real tears came into his eyes when, in Four Sons, Margaret Mann blessed him!

His parents being stage people, Charles trouped all over this country and Europe as a child.

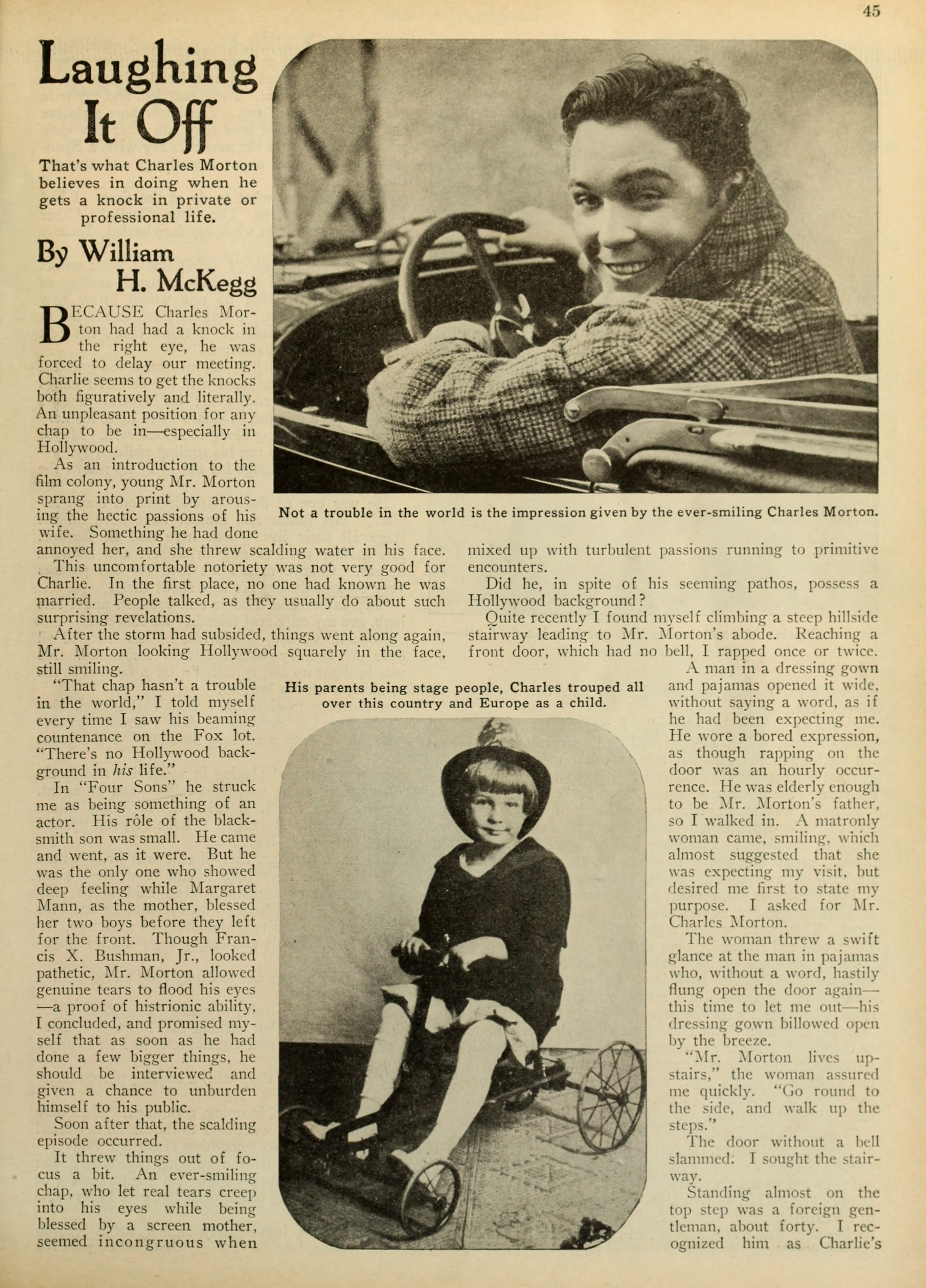

Not a trouble in the world is the impression given by the ever-smiling Charles Morton.

It was Charles Morton’s smile that got him his first role lead in “Rich But Honest.”

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, September 1929

Charles Morton did so well in loving Janet Gaynor, straying from her and returning, in “The Four Devils,” that he will be given the opportunity to do right by the girl in “Christina,” and be a good actor as well.

Photo by: Max Munn Autrey (1891–1971)

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, February 1929