Catherine Calvert — More Genuine Than Usual (1921) 🇺🇸

“I hope that I never read an interview with Catherine Calvert,” the irrepressible young thing just home from boarding school announced emphatically.

by Barbara Little

And to my “Why?” of surprise, she explained, “I don’t want to be disillusioned. They would probably say that she wore tailored suits, drove her own car, and liked chocolate cake. I couldn’t bear it. There’s little enough romance in the world as it is.”

Thus spoke the wisdom of sixteen.

We were “doing” the Metropolitan Museum of Art, that wonderful art gallery that is located in Central Park, and before at least one painting in every room my enthusiastic companion stopped, and said: “She looks just like that sometimes,” following it with the curt explanation, “Catherine Calvert, I mean.”

“But she couldn’t, honey. One of them was a Spanish dancer, another was a colonial belle, and another a medieval Madonna. They were absolutely different.”

“Well, so is she. Every part is as different and as filled with romance as those pictures back there. And I am scared to death that some one will tell me that in real life she is not romantic, or-that she reads humorous weeklies, or that she chums around with other stars.”

My young friend can stop worrying, for I have met Catherine Calvert, and she does none of those things. She is as real and as different as her characters on the screen.

You would no more think of being jocular about some persons than you would of jazzing “Pomp and Circumstance,” or drawing a caricature of your favorite screen star. That is the way you would feel about Catherine Calvert if you met her. I had supposed that she shed the grand manner she wears on the screen, and became just like one of us, when she wasn’t working before the camera, because I have known lots of other stars to be like that. But Catherine Calvert isn’t. Not that she is cold or distant or anything of the sort — she is just exalted. You can’t imagine her putting on a bungalow apron on the cook’s night off and getting dinner; you can easily picture her in an old English garden clipping roses. You can’t imagine her clinging to the seat of a chummy roadster, but she seems perfectly at ease in a luxuriously appointed limousine. She is the very antithesis of the girl who says, “Give me a good jazz band and a crowd of friends, and that’s all I’ll ask.” Such a thought could never occur to Catherine Calvert.

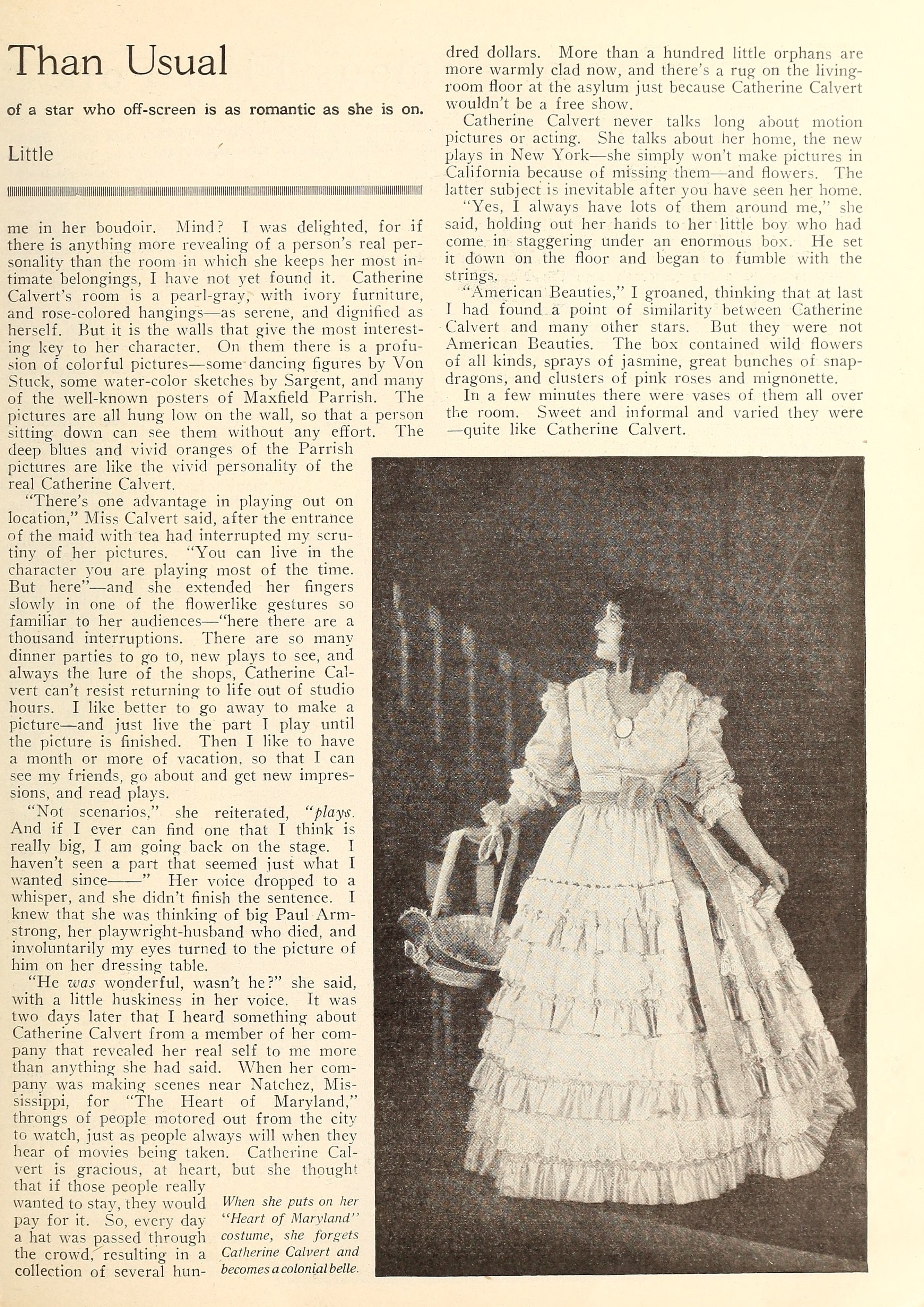

“Well, as a matter of fact, my life is just one costume after another,” Catherine Calvert told me, when I repeated to her the episode of the pictures in the museum. “I really ought to believe in reincarnation or something of the sort, because when I put on old colonial costumes, such as I wear in ‘The Heart of Maryland,’ or mantillas, such as I wore in ‘Dead Men Tell No Tales,’ Catherine Calvert ceases to exist, and I become a colonial belle,, or a Spanish girl. I even find that my taste in reading changes with my parts. When I was down in Natchez, Mississippi, doing some of the scenes for The Heart of Maryland, I found some novels written at the time the action of that story took place, and I was so delighted with them, I read nothing else the whole time.”

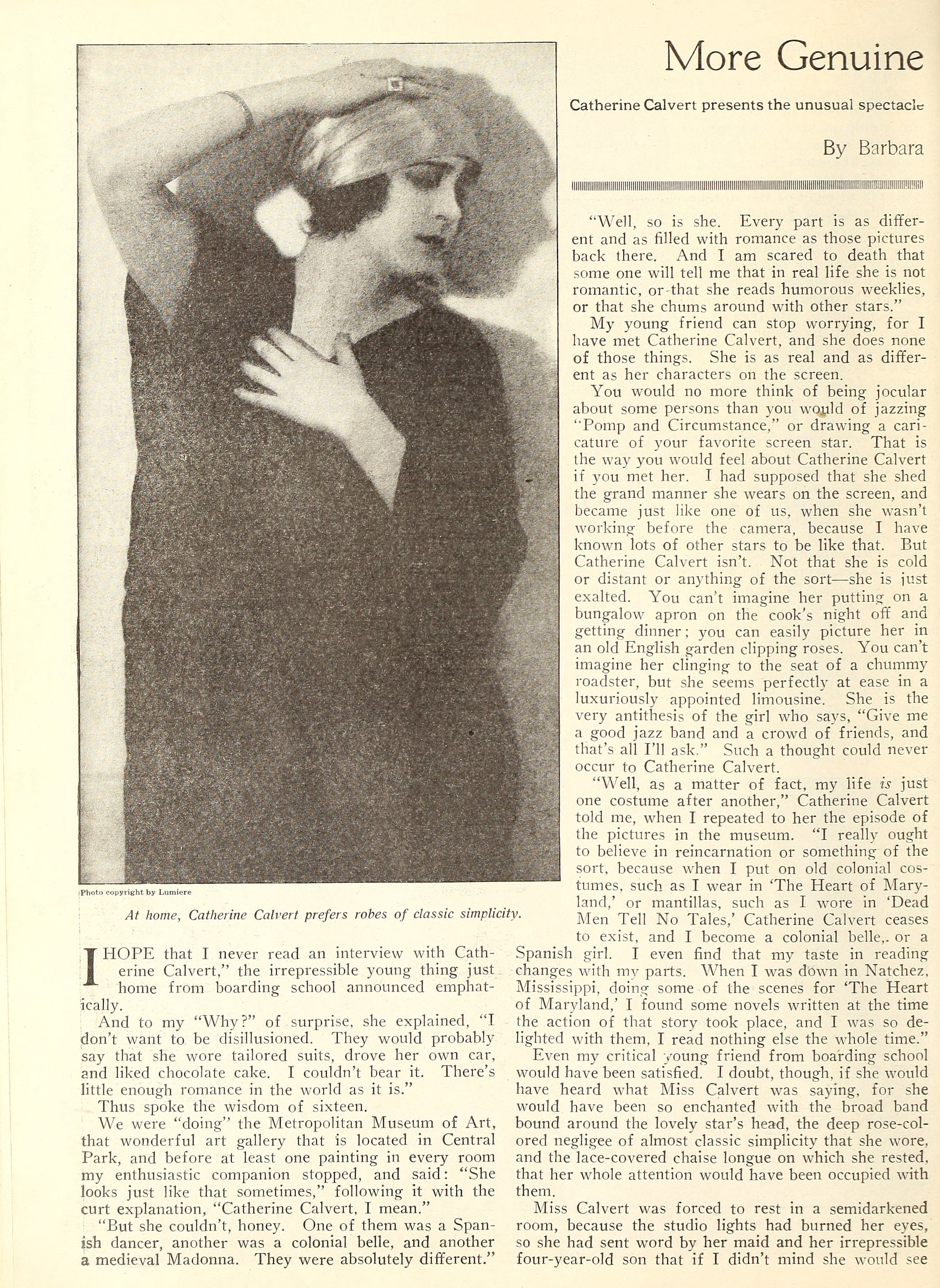

Even my critical young friend from boarding school would have been satisfied. I doubt, though, if she would have heard what Miss Calvert was saying, for she would have been so enchanted with the broad band bound around the lovely star’s head, the deep rose-colored négligée of almost classic simplicity that she wore, and the lace-covered chaise longue on which she rested, that her whole attention would have been occupied with them.

Miss Calvert was forced to rest in a semi-darkened room, because the studio lights had burned her eyes, so she had sent word by her maid and her irrepressible four-year-old son that if I didn’t mind she would see me in her boudoir. Mind? I was delighted, for if there is anything more revealing of a person’s real personality than the room in which she keeps her most intimate belongings, I have not yet found it. Catherine Calvert’s room is a pearl-gray, with ivory furniture, and rose-colored hangings — as serene, and dignified as herself. But it is the walls that give the most interesting key to her character. On them there is a profusion of colorful pictures — some dancing figures by Von Stuck, some water-color sketches by Sargent, and many of the well-known posters of Maxfield Parrish. The pictures are all hung low on the wall, so that a person sitting down can see them without any effort. The deep blues and vivid oranges of the Parrish pictures are like the vivid personality of the real Catherine Calvert.

“There’s one advantage in playing out on location,” Miss Calvert said, after the entrance of the maid with tea had interrupted my scrutiny of her pictures. “You can live in the character you are playing most of the time. But here” — and she extended her fingers slowly in one of the flowerlike gestures so familiar to her audiences — “here there are a thousand interruptions. There are so many dinner parties to go to, new plays to see, and always the lure of the shops, Catherine Calvert can’t resist returning to life out of studio hours. I like better to go away to make a picture — and just live the part I play until the picture is finished. Then I like to have a month or more of vacation, so that I can see my friends, go about and get new impressions, and read plays.

“Not scenarios,” she reiterated, “plays. And if I ever can find one that I think is really big, I am going back on the stage. I haven’t seen a part that seemed just what I wanted since —” Her voice dropped to a whisper, and she didn’t finish the sentence. I knew that she was thinking of big Paul Armstrong, her playwright-husband who died, and involuntarily my eyes turned to the picture of him on her dressing table.

“He was wonderful, wasn’t he?” she said, with a little huskiness in her voice. It was two days later that I heard something about Catherine Calvert from a member of her company that revealed her real self to me more than anything she had said. When her company was making scenes near Natchez, Mississippi, for The Heart of Maryland, throngs of people motored out from the city to watch, just as people always will when they hear of movies being taken. Catherine Calvert is gracious, at heart, but she thought that if those people really wanted to stay, they would pay for it. So, every day a hat was passed through the crowd resulting in a collection of several hundred dollars. More than a hundred little orphans are more warmly clad now, and there’s a rug on the living-room floor at the asylum just because Catherine Calvert wouldn’t be a free show.

Catherine Calvert never talks long about motion pictures or acting. She talks about her home, the new plays in New York — she simply won’t make pictures in California because of missing them — and flowers. The latter subject is inevitable after you have seen her home.

“Yes, I always have lots of them around me,” she said, holding out her hands to her little boy who had come in staggering under an enormous box. He set it down on the floor and began to fumble with the strings.

“American Beauties,” I groaned, thinking that at last I had found a point of similarity between Catherine Calvert and many other stars. But they were not American Beauties. The box contained wild flowers of all kinds, sprays of jasmine, great bunches of snap-dragons, and clusters of pink roses and mignonette.

In a few minutes there were vases of them all over the room. Sweet and informal and varied they were — quite like Catherine Calvert.

—

At home, Catherine Calvert prefers robes of classic simplicity

Photo copyright by Lumière

—

When she puts on her “Heart of Maryland” costume, she forgets Catherine Calvert and becomes a colonial belle.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, April 1921