Bryant Washburn — The Road to London (1921) 🇺🇸

When I put in a query for Bryant Washburn at his office in the Brunton studios, the stenographer glanced up snippily and replied: “Mr. Washburn is very busy. He’s getting ready to go over the road to London.”

by Edwin Schallert

“You don’t say so!” I exclaimed. “I thought he just came back from there. What’s he going again for?”

She tossed her head and said: “Well, you can’t see him unless you have an appointment.”

“But I have. And I’ve got to see him before he leaves,” I answered with melodramatic emphasis.

After gazing at me quizzically and asking my name, she clicked the lock on the door that led to the lot.

I caught sight of Mr. Washburn close by, surrounded by a group of technical experts, and hurried up to him.

“How are you traveling, Mr. Washburn?” I asked, with visions of everything in mind from an airplane to a wheel cart, inspired by the stenographer’s jauntily expressed information about the trip abroad.

“Traveling?” he exclaimed. “Traveling? I’ve had enough of traveling for a while. After a five-thousand-mile location trip to England, I’m glad to be back in Hollywood. There’s no place on earth like it. Why — you can build your interior sets a thousand times better here. And they look as good as any English drawing-room or hotel lobby. That’s a certainty. But it is different with the exteriors. They’re great abroad, and —”

I gasped, but managed to explode a question before he got any further.

“Aren’t you going to London again?” And I explained what the girl had told me.

“Right enough.” he laughed. “We are going over The Road to London. That’s the film I shot in England, and that’s what she meant. She’s a cute girl.”

I made up my mind right then that Mr. Washburn might know a lot about pioneering camera expeditions, but that he didn’t know much about women — even if he was married — especially fresh stenographers. One never can tell, of course, but I recalled that I had a rather serene impression of him as a real home-loving star. Incidentally, I made no my mind that his stenographer was off my calling list, until she mended her manners toward interviewers.

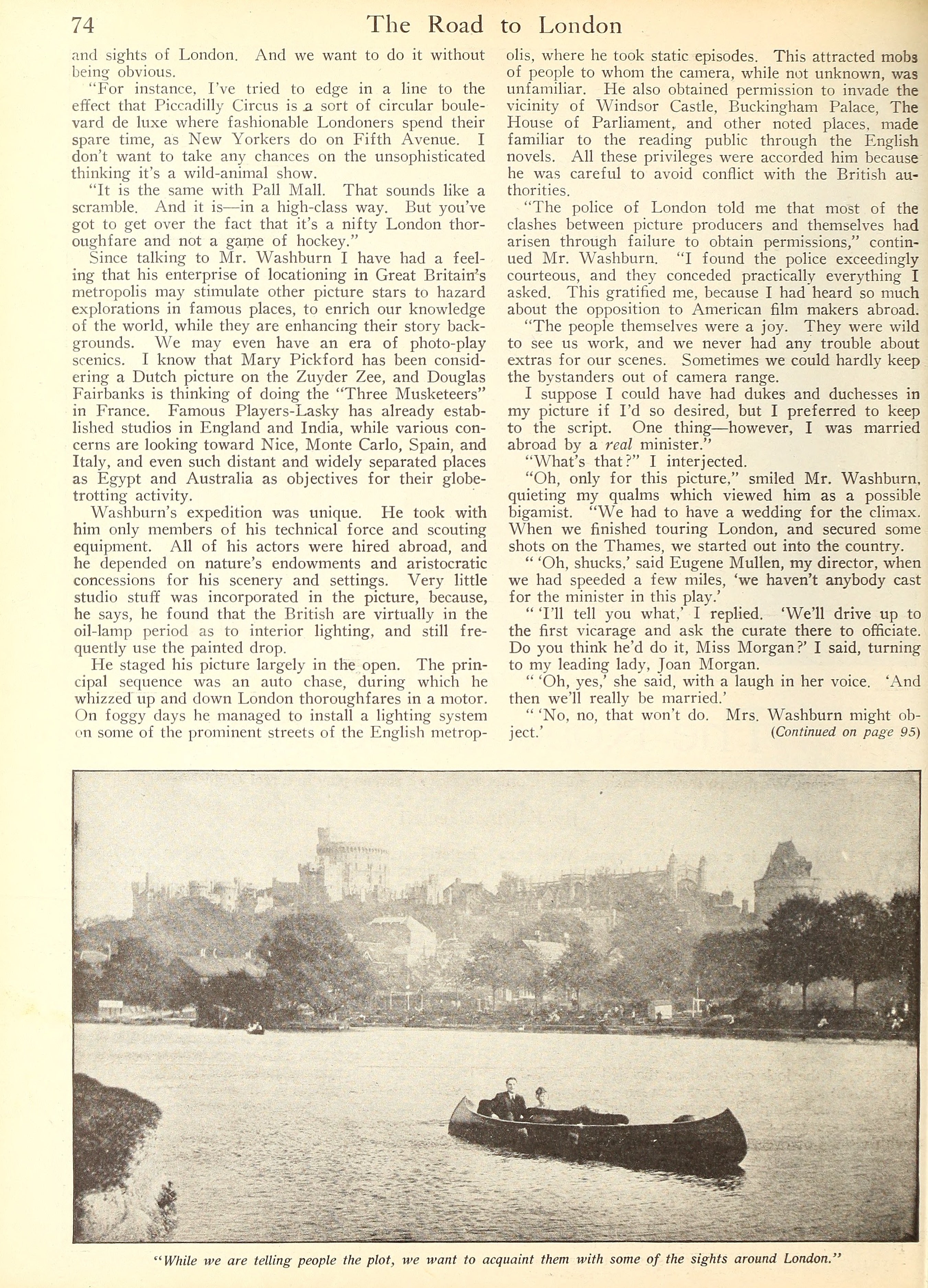

“We’ve just been discussing subtitles,” continued Washburn, indicating his surrounding court. “We have a picture here which is something of a scenic. So while we’re telling people the plot — we haven’t slighted the story — we’re trying to acquaint them with the geography and sights of London. And we want to do it without being obvious.

“For instance, I’ve tried to edge in a line to the effect that Piccadilly Circus is a sort of circular boulevard de luxe where fashionable Londoners spend their spare time, as New Yorkers do on Fifth Avenue. I don’t want to take any chances on the unsophisticated thinking it’s a wild-animal show.

“It is the same with Pall Mall. That sounds like a scramble. And it is — in a high-class way. But you’ve got to get over the fact that it’s a nifty London thoroughfare and not a game of hockey.”

Since talking to Mr. Washburn I have had a feeling that his enterprise of locationing in Great Britain’s metropolis may stimulate other picture stars to hazard explorations in famous places, to enrich our knowledge of the world, while they are enhancing their story backgrounds. We may even have an era of photo-play scenics. I know that Mary Pickford has been considering a Dutch picture on the Zuyder Zee, and Douglas Fairbanks is thinking of doing the Three Musketeers in France. Famous Players-Lasky has already established studios in England and India, while various concerns are looking toward Nice, Monte Carlo, Spain, and Italy, and even such distant and widely separated places as Egypt and Australia as objectives for their globetrotting activity.

Washburn’s expedition was unique. He took with him only members of his technical force and scouting equipment. All of his actors were hired abroad, and he depended on nature’s endowments and aristocratic concessions for his scenery and settings. Very little studio stuff was incorporated in the picture, because, he says, he found that the British are virtually in the oil-lamp period as to interior lighting, and still frequently use the painted drop.

He staged his picture largely in the open. The principal sequence was an auto chase, during which he whizzed up and down London thoroughfares in a motor. On foggy days he managed to install a lighting system on some of the prominent streets of the English metropolis, where he took static episodes. This attracted mobs of people to whom the camera, while not unknown, was unfamiliar. He also obtained permission to invade the vicinity of Windsor Castle, Buckingham Palace, The House of Parliament, and other noted places, made familiar to the reading public through the English novels. All these privileges were accorded him because he was careful to avoid conflict with the British authorities.

“The police of London told me that most of the clashes between picture producers and themselves had arisen through failure to obtain permissions,” continued Mr. Washburn. “I found the police exceedingly courteous, and they conceded practically everything I asked. This gratified me, because I had heard so much about the opposition to American film makers abroad.

“The people themselves were a joy. They were wild to see us work, and we never had any trouble about extras for our scenes. Sometimes we could hardly keep the bystanders out of camera range.

I suppose I could have had dukes and duchesses in my picture if I’d so desired, but I preferred to keep to the script. One thing — however, I was married abroad by a real minister.”

“What’s that?” I interjected.

“Oh, only for this picture,” smiled Mr. Washburn, quieting my qualms which viewed him as a possible bigamist. “We had to have a wedding for the climax. When we finished touring London, and secured some shots on the Thames, we started out into the country.

“‘Oh, shucks,’ said Eugene Mullen, my director, when we had speeded a few miles, ‘we haven’t anybody cast for the minister in this play.’

“‘I’ll tell you what,’ I replied. ‘We’ll drive up to the first vicarage and ask the curate there to officiate. Do you think he’d do it, Miss Morgan?’ I said, turning to my leading lady, Joan Morgan.

“‘Oh, yes,’ she said, with a laugh in her voice. ‘And then we’ll really be married.’

“‘No, no, that won’t do. Mrs. Washburn might object.’

“‘Oh, it wouldn’t be legal.’ answered Miss Morgan breezily. ‘The bans haven’t been published!’

“‘Well, I’ll take a chance,” I said. Striving to remain faithful and be game at once, but with expectation of having to explain several things to Mrs. Washburn — who accompanied me on my tour abroad — upon my return to our hotel.

“We drew up at the vicarage of the Reverend Doctor Batchelder, whom Miss Morgan happened to know personally, and he didn’t manifest the least opposition to performing the ceremony for the films, because it gave him a thrill to act in them.”

Most of the players engaged abroad for The Road to London had had stage or screen experience. Prominent parts were assigned to Saba Raleigh, widow of the late Cecil Raleigh, the writer, and Gibbs McLaughlin, an English actor. Miss Morgan, the leading woman, had been in the films in America, as lead for Henry Miller in an early production.

Among the nonprofessional people who took part in Mr. Washburn’s photo play was Sir Bertram Hayes, captain of the Olympic, who was in some scenes staged aboard the steamer.

The Road to London is Mr. Washburn’s first independent production, following the termination of his contract with Famous Players-Lasky. He chose to film it abroad because he wanted a distinctive beginning to his independent career. His experience was especially valuable in acquainting him with the opportune season for London feature-making.

“I would not advise anybody to go to England to make pictures later than May,” he declared. “We set out in June, and we had to race against oncoming winter in the final scenes. If we hadn’t there would have been flaws in our scenery owing to the falling of the leaves.

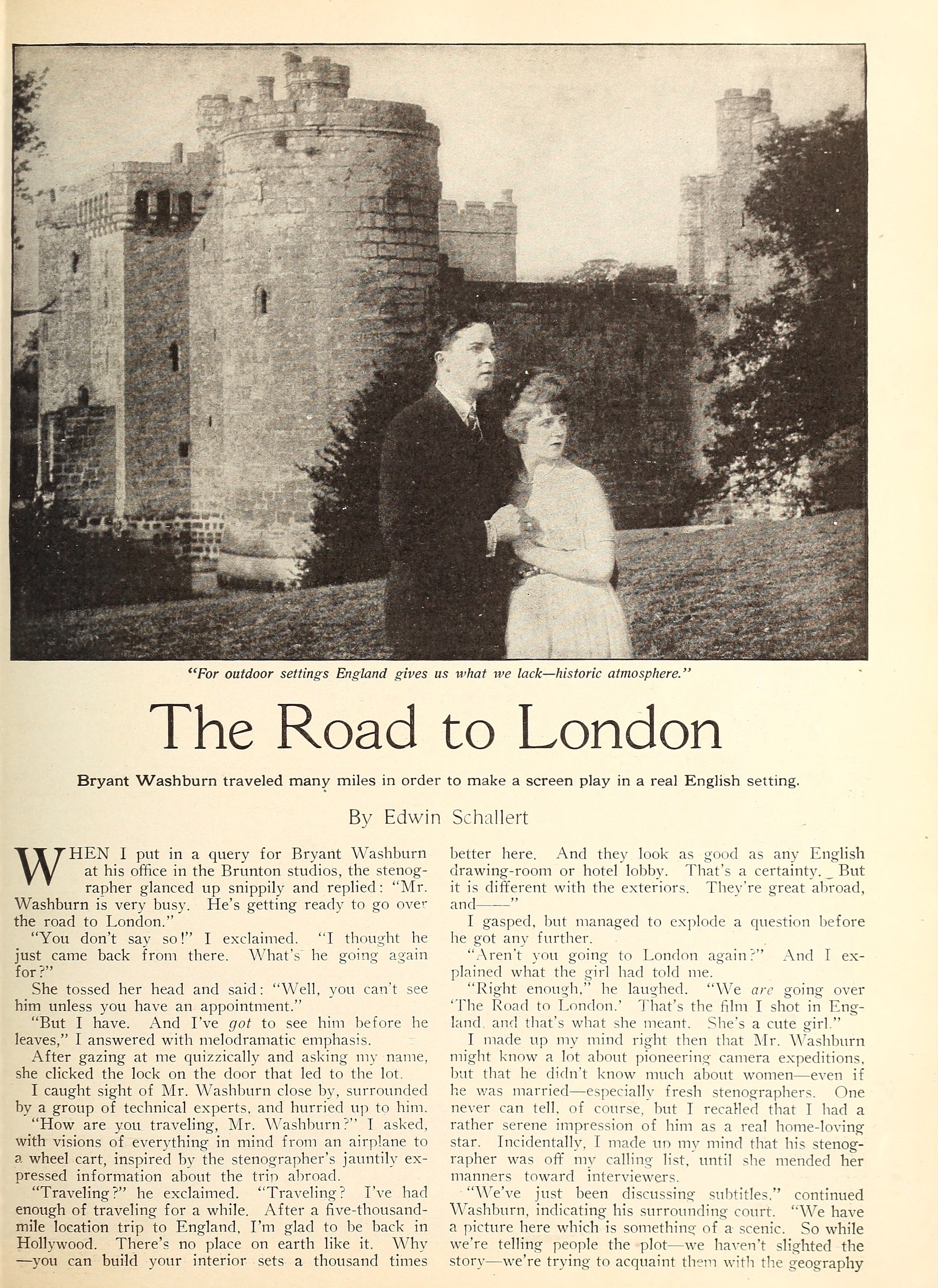

“The summer is fine abroad, and England is enriched with natural attractions that are only to be compared to a Corot landscape. The dwellings and public buildings possess what we lack in America — historic atmosphere. I am greatly elated over my outdoor shots, because they speak so eloquently of aristocratic grandeur and picturesque nature. In fact, I should rather like to return to England again this year to make another picture.”

“For outdoor settings England gives us what we lack — historic atmosphere.”

“While we are telling people the plot, we want to acquaint them with some of the sights around London.”

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, July 1921