William S. Hart — After Four Years (1929) 🇺🇸

“Will you kiss your daddy goodbye, son?” Bill Hart asked his boy. “I will if you don’t cry again,” said the little fellow.

by Rosalind Shaffer

He was only three then, but he knew that something pretty terrible was tearing the heartstrings of the gaunt, thin-lipped man who was on his knees before him. Bill Hart clasped the little son he had not held in his arms since the sixth day of the boy’s life, and composed his features with all the strength he could summon. “Goodbye, son,” he said. “Be a good boy.”

That meeting was hail and farewell, for William S. Hart has never seen his boy since. That was four years ago. It was Bill Hart, Jr.’s third birthday. I took the baby from his party to make a brief call on his father. I tremble now when I think of my boldness, for at that time I was not acquainted with Bill Hart.

I came forth shaken to the soul. There was a feeling that I had trespassed in the sanctuary of a human heart, a heart wounded almost unto death. Like others, I had wondered what lay behind the silence and mystery of this man.

No accusation had ever drawn forth an answer, only silence. Now the reason became clear. There was that little golden -haired boy with his father’s face. He would grow up to bear an honored name. Bill Hart was seeing to that in his own way… and I understood for the first time that a great heart in its wisdom had seen beyond selfishness to renunciation. Two years later, in a windswept pass in the mountains beyond Truckee, I met Bill Hart again. It was bitter cold, for it was February in the Sierras. The deputies seeking to serve Hart with his wife’s divorce papers had consented to take a rather frozen but ambitious female reporter from Reno along.

“We just didn’t hitch,” said Bill… and the world wondered and did not understand why he gave no sign. Bill Hart went home to a sickbed and lay in danger of his life. It was not all cold weather that did that. There was something in that face that was not the cold, that day in the mountain pass. There are some riddles in life that two guns are powerless against. Broken dreams, for instance.

You see there was a group of trees on a hillside that would never see a little boy playing Indian with his tipi pitched under their shade, as the little boy’s father had dreamed. There is the little boy, but he lives in an apartment in Hollywood, and his father walks alone under those trees. The apartment is luxurious, due to the father’s generosity, but there are only women there — not any father, not tipis, and trees and God’s great outdoors, where a lit tie boy can play Indian and listen to his father’s stories of his own boyhood, and his Indian friends.

Somewhere in the Divine Weaver’s plan, is the reason that domestic tragedy had to come to Bill Hart. A dream of a home had sustained him through all the years when he had been battling his way towards recognition on the stage, and again on the screen. He had his little family, his mother and sisters, who battled poverty with him and helped hearten him to win the great fame that is his today. A home of his own had to wait for material success; a home that he had visioned through the years, with children, and a wife and mother who would hold the sacred trust of building a home higher than any passing glory of career or fame.

There were plenty of women ready to help Bill Hart make that dream come true. Nothing of a gallant about him, yet Hart’s charm was so potent that one society woman of prominence, who had never seen him except on the screen, was willing to give up her home and her husband, if she could have gained the slightest hearing with Hart. This case is known to me personally; there were others as well.

When Pola Negri came to Hollywood it was not long before the exotic and beautiful cyclone was telling reporters, “My beeg strong he-man of the Wes’, he will protec’ little Pola.”

Before this time, Norma Talmadge had become aware of the inscrutable charm of the strong silent man, and blushingly admitted to intimates that she was going to marry William S. Hart.

Years before that, a lovers’ quarrel had separated Bill Hart and Louise Dresser. If you question Bill about all the lovely women who have cared for him, he looks embarrassed, tugs at a tuft of his hair and says laughingly, “Well, you see, they all got wise to me, I just didn’t measure up, I reckon.” He kept steadily searching for one who would put aside ambition for him, and be a wife and mother.

Prince Charming married Cinderella, leading all the princesses and ladies of the court to weep, but something went wrong, for the golden coach changed back to a pumpkin, the glass slipper was broken and the ashes were cold. Five months found the ends of the rainbow together.

Shortly after this, business troubles arose. Methods were shifting in the rapidly growing picture industry. Can you imagine Bill Hart wearing white kid and patent leather riding boots? And white serge tailored riding clothes with black satin piping? And a white sombrero with white kid gauntlets? No — and neither could he. That was why Bill Hart did not go on with his film work. His producers demanded that Bill, who was then a producer, give up all say about his pictures, his stories, and his work, and become simply an actor, subject to dictates from folks in New York who never saw an Indian nor a cowboy.

“I have faith to keep with the public,” said Bill. “Do you think I could do fake stuff for all those little boys, and the big ones too, who have learned to love my pictures? No, I’ll quit first. Do you think I could go among my Indian friends without hanging my head in shame, if I presented them falsely to the public? They could never understand my doing such a thing, because they know that I know better.”

With his dreams of a home gone glimmering and the conflict between Hart’s ideals of sincerity in his work and the new efficiency methods of the industry. Hart sought retirement.

Only his most intimate friends at small gatherings saw the stalwart, silent man. Hollywood first nights and the public functions, at which he had always been greeted with almost hysterical applause from the fans, saw him no more. He preferred to spend more and more of his time at the Horseshoe Ranch, out past Newhall on the edge of the desert. Fritz, the little pinto, and Cactus Kate, and Lisbeth, the mule, understood in their dumb way the hurt and sorrow of it all. Perhaps they understood better than most folks, because their beloved master couldn’t talk to people about things very well.

There is sometimes more comfort for the wounds given by one human being to another in fingering the soft ear of a faithful dog whose eyes speak the comfort he can’t tell. The velvety soft nose of a horse brushing one’s cheek can be a powerful comfort when all the world seems wrong and mixed up.

Four years of retirement, of absence from the screen, and the fan letters are still coming to Bill, to the tune of two hundred a day. Rudolph Valentino was absent from the screen for two years after his differences with those same producers and his backers were very worried over the possibility of that great lover making a comeback. As for Bill Hart’s fans, for them he never has been away. There never will be but one Bill Hart.

This popular demand was recognized by the Victor Phonograph Company when last spring they invited Hart to make several talking records. They got the best talking records they ever made. Incidentally, they rediscovered a glorious golden voice that the film fans had never suspected.

Dion Boucicault and such men of the theater had trained it. Audiences had thrilled to that voice when Bill Hart played John Storm in The Christian; when the stage’s first Messala in Ben-Hur was played by Hart; Julia Arthur chose him for her Sir John Oxen in A Lady of Quality, and for Romeo to her Juliet; Madame Helena Modjeska employed Hart as leading man, and liked his Armand to her Camille better than any other actor’s she ever played with. Robert Mantell, assembling a Shakespearean company, selected Bill Hart for prominent roles with him.

It is amazing the number of unfortunates that have turned to Bill Hart’s great heart for aid. I know personally of cases where Hart furnished money to aid girls he had never seen. Bill just trusts folks... and believes in them. No man can boast a more loyal and distinguished circle of friends than Bill Hart.

Hollywood was as excited as the fan public when Hal Roach sent out word that Hart was to return to the screen, with a talking picture. Then came the incredible news that the releasing company did not think the public wanted a Western talkie.

This opinion hardly seems based on facts as reflected in the flood of fan mail. The public’s feeling is still more clearly shown towards Bill Hart in the enormous sales of his recently published autobiography, My Life East and West. This book not only has enjoyed a large sale, but it has elicited letters from senators, judges, and people of prominence all over the country.

The millions of dollars that would have been earned for the motion picture industry during the years that he has been allowed to be idle, are now gone into oblivion. That is no reason, however, that the same state of affairs should be allowed to go on indefinitely. Bill Hart’s appeal is ageless; he never was a juvenile on the screen, and his sturdy manhood is as appealing to fans today as it was at the height of his screen career. ‘With the coming of the talkies, and Hart’s demonstration that he has something unusual to offer in his voice, it seems incomprehensible that such a bet will be ignored indefinitely because of the old business feuds of the past.

Bill Hart does not need to come back to films for his own sake. He has a beautiful home, filled with material comforts. He has his writing, at which he has scored success; his horses, and all the little concerns of his small world on the ranch. He has his friends. The reason that Bill Hart should come back is because the fans want him back, and the industry needs him back.

Bill and I had along talk about all this up at the ranch at Newhall just after the cancellation of the contract with Roach. Pictures taken of Hart at that time show him as good a photographic subject as he ever was; he is fit physically, with the daily activity of his life as gentleman rancher.

It was late afternoon of a hot summer’s day whenlleft the Horseshoe Ranch and its hilltop hacienda. The car, with its gears grinding, rolled protestingly down the hill. Over my shoulder I could see the gentle, stalwart figure of Bill Hart outlined against the Western sky. Maybe it was a fantasy born of the heat; perhaps it was the magic of the souls of those brave men and true of the Old West, who have lived again in Hart’s characterizations; but the figure seemed to become taut, thin lipped, grim, cold and narrow eyed, with two guns slung at the side.

Looking across the gates of Bill Hart’s ranch at Newhall. Here, but for domestic tribulations, Bill’s little boy, Bill, Jr., now seven, would be playing happily

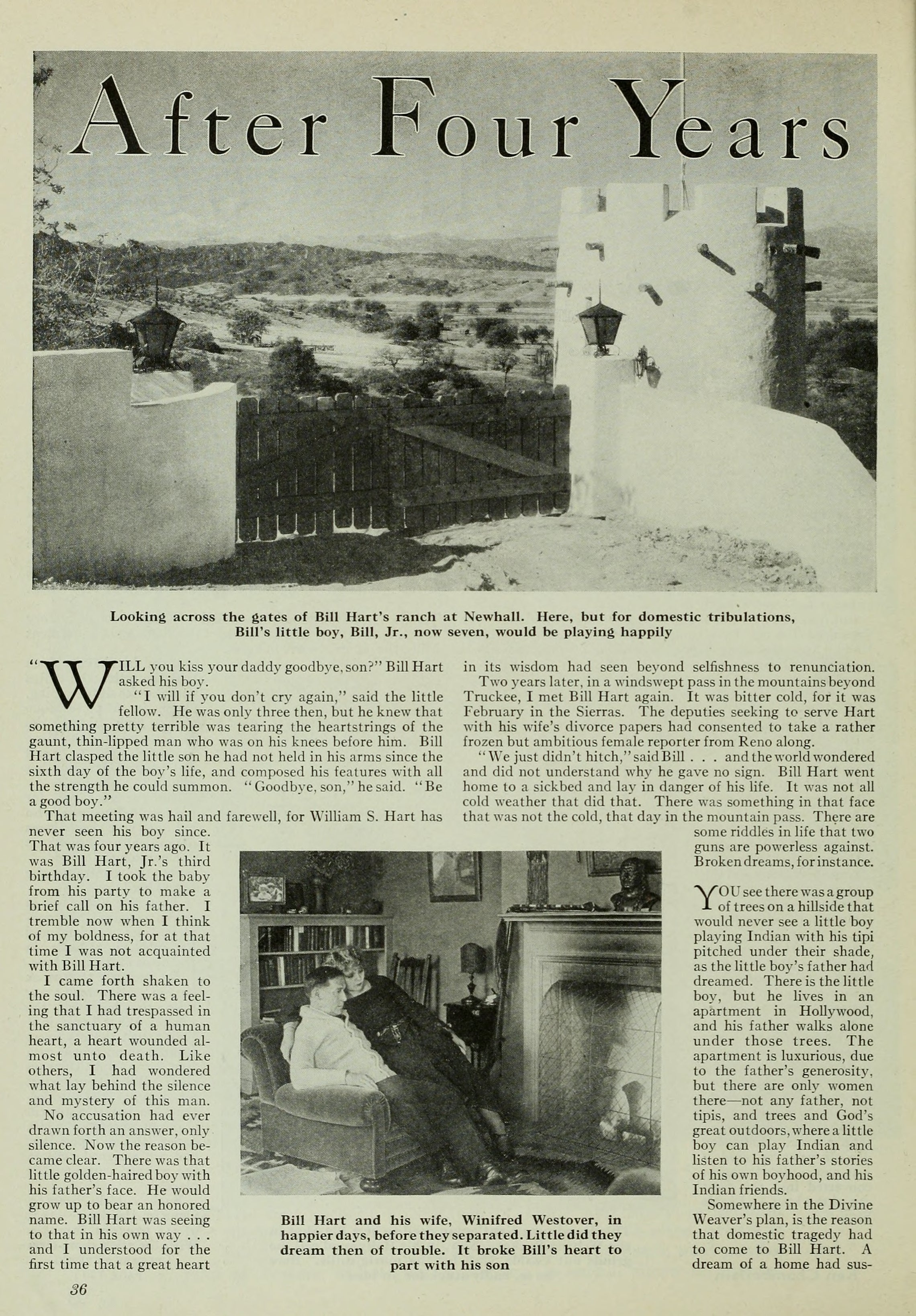

Bill Hart and his wife, Winifred Westover, in happier days, before they separated. Little did they dream then of trouble. It broke Bill’s heart to part with his son

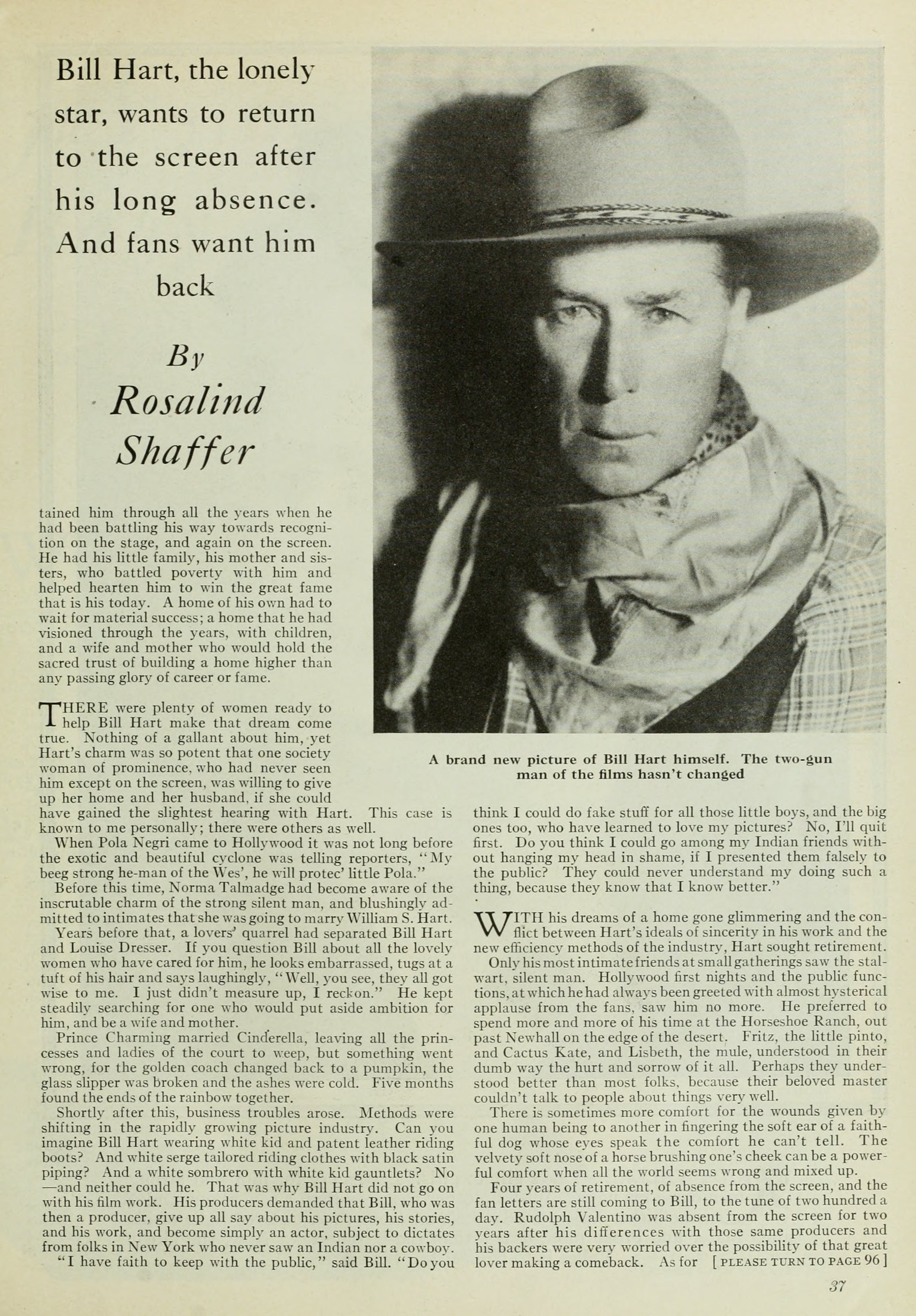

A brand new picture of Bill Hart himself. The two-gun man of the films hasn’t changed

Dustin Farnum and Bill Hart — when they both were starring in Western dramas. Farnum died a few weeks ago after a year’s illness and a long retirement from pictures

Every advertisement in Photoplay Magazine is guaranteed.

Collection: Photoplay Magazine, October 1929