William Collier Jr. — Up and Down with Buster (1927) 🇺🇸

Buster Collier and I met casually about a year ago, then I didn’t see him again until just the other day. A mutual friend had called me on the phone one lazy evening. He said, “I’m over at Buster Collier’s. He’s feeling low — why couldn’t we all go to the Orpheum?”

by Ann Sylvester

I said it was agreeable, and in half an hour a car came and piloted me over to Buster’s.

He lived in the Mexican village at the time. It is deliberately picturesque. A kittenish fountain splashes all over the courtyard on which the apartments open. I pushed the bell over the card marked “Buster Collier.”

I wondered what the dickens he was low about. None of my business, really.

The mutual friend was there, and said Buster would be with us in a minute. “What’s he low about?” I inquired rudely. Our friend shrugged his shoulders. I don’t know why I was so curious about it.

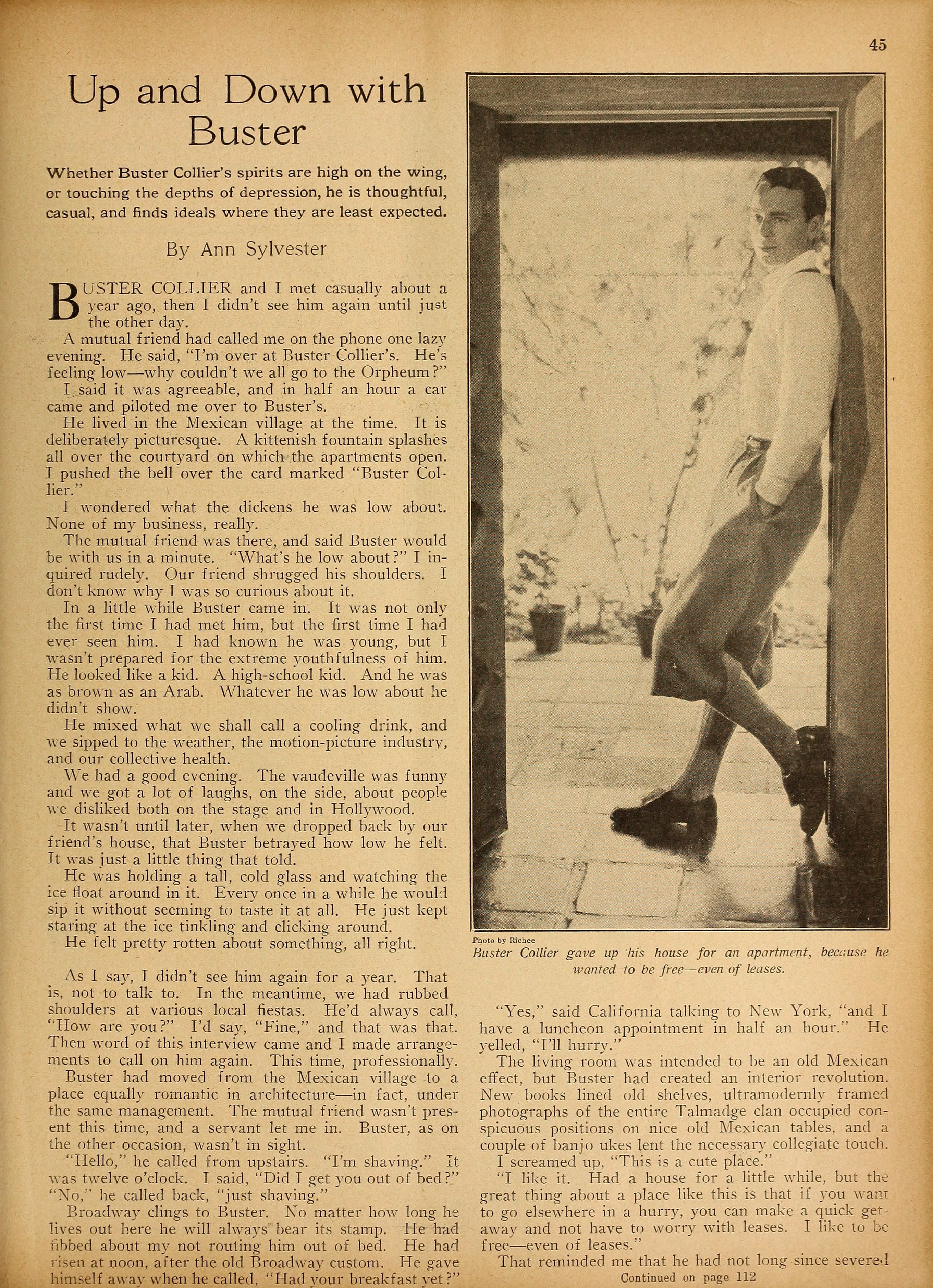

In a little while Buster came in. It was not only the first time I had met him, but the first time I had ever seen him. I had known he was young, but I wasn’t prepared for the extreme youthfulness of him. He looked like a kid. A high-school kid. And he was as brown as an Arab. Whatever he was low about he didn’t show.

He mixed what we shall call a cooling drink, and we sipped to the weather, the motion-picture industry, and our collective health.

We had a good evening. The vaudeville was funny and we got a lot of laughs, on the side, about people we disliked both on the stage and in Hollywood.

It wasn’t until later, when we dropped back by our friend’s house, that Buster betrayed how low he felt. It was just a little thing that told.

He was holding a tall, cold glass and watching the ice float around in it. Every once in a while he would sip it without seeming to taste it at all. He just kept staring at the ice tinkling and clicking around.

He felt pretty rotten about something, all right.

As I say, I didn’t see him again for a year. That is, not to talk to. In the meantime, we had rubbed shoulders at various local fiestas. He’d always call, “How are you?” I’d say, “Fine,” and that was that. Then word of this interview came and I made arrangements to call on him again. This time, professionally.

Buster had moved from the Mexican village to a place equally romantic in architecture — in fact, under the same management. The mutual friend wasn’t present this time, and a servant let me in. Buster, as on the other occasion, wasn’t in sight.

“Hello,” he called from upstairs. “I’m shaving.” It was twelve o’clock. I said, “Did I get you out of bed?” “No,” he called back, “just shaving.”

Broadway clings to Buster. No matter how long he lives out here he will always bear its stamp. He had fibbed about my not routing him out of bed. He had risen at noon, after the old Broadway custom. He gave himself away when he called, “Had your breakfast yet?”

“Yes,” said California talking to New York, “and I have a luncheon appointment in half an hour.” He yelled, “I’ll hurry.”

The living room was intended to be an old Mexican effect, but Buster had created an interior revolution. New books lined old shelves, ultra-modernly framed photographs of the entire Talmadge clan occupied conspicuous positions on nice old Mexican tables, and a couple of banjo ukes lent the necessary collegiate touch.

I screamed up, “This is a cute place.”

“I like it. Had a house for a little while, but the great thing about a place like this is that if you want to go elsewhere in a hurry, you can make a quick getaway and not have to worry with leases. I like to be free — even of leases.”

That reminded me that he had not long since severed

his connection with Paramount, and in a voice loud enough for him to hear, I brought up the subject of his break.

I could hear him puttering around upstairs, but he stopped long enough to call, “I’m glad to get away. Contracts are likely to do you more harm than good, unless you are big enough to demand your own roles.” He was coming down now. As he trotted into the living room, freshly shaven, he repeated, “Hello.”

He looked as ridiculously young as ever, and he was in radiant good humor.

“I’m having a lot of fun making a couple of ‘quickies.’” For the benefit of the unenlightened, a quickie is a picture made by a small company for very little money and in even less time.

“There is where the real adventure of picture making is,” Buster beamed. “These corporation pictures have lost their romance. There’s no plotting or planning, or even any creation, connected with them. You are always sure the money is going to hold out, and even if it doesn’t stay within its financial quota, there’s always more where that came from. But in the quickies you’re on your toes all the time. You’ve got to use your wits and your brains. This man, Phil Goldstone — Lord! I’ve the greatest admiration for that man. He can take fifty thousand dollars and make it look like any other producer’s one hundred thousand dollars. That is because he is directly in touch with his money, himself. Other executives just get reports on theirs.

“I’m crazy to do something like that myself — to get hold of a production and make it for just a little money. Create the thing. That’s the greatest kick in this business. There’s no kick in acting. You do what you are told, and paid, to do.” Coming from the scion of an old theatrical family, his disrespect for the art of acting was radical, to say the least.

The stepson of the famous Willie Collier [William Collier Sr.], Buster has been connected with the stage all his life. He was born to his work. He did child roles on the stage until he reached the awkward age, and then went to live on the family farm. Having nothing else to do, he learned to ride like a cowboy. His youth alternated between dressing room and saddle.

Just about the time that Buster was slipping out of childhood, D. W. Griffith, Thomas H. Ince, and Mack Sennett combined their individual strength and formed a big company — the Triangle. They brought out a lot of stage favorites from New York at tremendous salaries. Among them was William Collier — and Buster.

Buster got the movie bug. He got it so bad that he insisted on playing the puny role of an office boy in one of his father’s pictures for Ince. Buster did so well in it that the director developed it into quite a good little part. Ince saw it in the projection room. “Who’s that?” he asked Collier, Sr.

“That’s my kid.”

Ince said, “H’m!”

That “H’m!” developed into Buster’s being starred in a picture entitled The Bugle Call. It’s the same story that Jackie Coogan is doing now.

“It was what we considered a super-production at the time,” Buster related. “We felt pretty proud of that one. There were fights, and mobs of extras, and all the other trimmings. I felt like Barrymore himself, being starred in such an undertaking. I got seventy-five dollars a week and I was almost ashamed to take so much money. I didn’t see how I could ever spend it.”

From then on Buster was of the movies. In fact, he became our foremost jockey. Whenever there was a race-track comedy or drama to be screened, Buster played it. He also did The Wanderer, his biggest and most spectacular role, but not his best. I think The Rainmaker was his best.

Since leaving Paramount he has free-lanced, principally on the First National lot, and in his much-admired quickies.

Some, one came in and said Buster’s breakfast was ready — and then there was my luncheon appointment. He walked out to the car with me.

“I’m helping Buster Keaton on his new picture — just helping out on the mobs, and yelling through a megaphone every chance I get — just for the experience,” he said as he helped me in. “You see, I’m really serious about making something of my own.”

He stood in the courtyard of this new Mexican place, bareheaded in the midday glare, and grinned as I pulled out. He looked more like a kid home on his college vacation than a potential Schenck [Joseph M. Schenck]. But that’s his aim.

He’s a great boy, this Buster, no matter whether he’s high on the wing, or deep in the dumps.

Buster Collier gave up his house for an apartment, because he wanted to be free — even of leases.

Photo by: Eugene Robert Richee (1896–1972)

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, August 1927