Victor Seastrom — New Hope for the American Photoplay (1923) 🇺🇸

Is Victor Seastrom, the Swedish Director, a New Force in Our World of the Cinema?

by Constance Palmer Littlefield

A black-robed figure, its youth and strength, subdued to stately step, heads a solemn procession through the cold austerity of an English courtroom. The moment is fraught with intensity, for this young man — the newly-made deemster— is to sit in judgment on a girl accused of killing her illegitimate baby. Out of all the world, only the girl and the judge know who the father of that child is.

The courtroom is crowded with spectators eager for details of the sordid tragedy. The girl, white-faced and cold in the extremity of her terror, has steadily refused to speak the name of her seducer. She has not faltered even though she knows that that seducer is the judge whom the prosecuting attorney is forcing into a pronunciation of the death sentence.

Back of this great dramatic conflict stand the minds of two men. One of them is Sir Hall Caine, who first created the situation in his The Master of Man. The other is Victor Seastrom, the director who is transferring that novel to the screen for Goldwyn.

Depends Upon the Director

In the hands of a weak man, the story could become merely a melodramatic sequence of fights, rainstorms, ranting villains, and noble heroes. Under the guidance of a certain loudmouthed director — incidentally my pet personal aversion — I can easily imagine the girl’s trouble resulting from a cafe drinking party in which three hundred and fifty extras blithely stick confetti down one another’s necks and thirty-two scantily-dressed Follies girls languish in the middle of the cleared dance-floor, thereby giving the exhibitors the pesky “big set” which he demands.

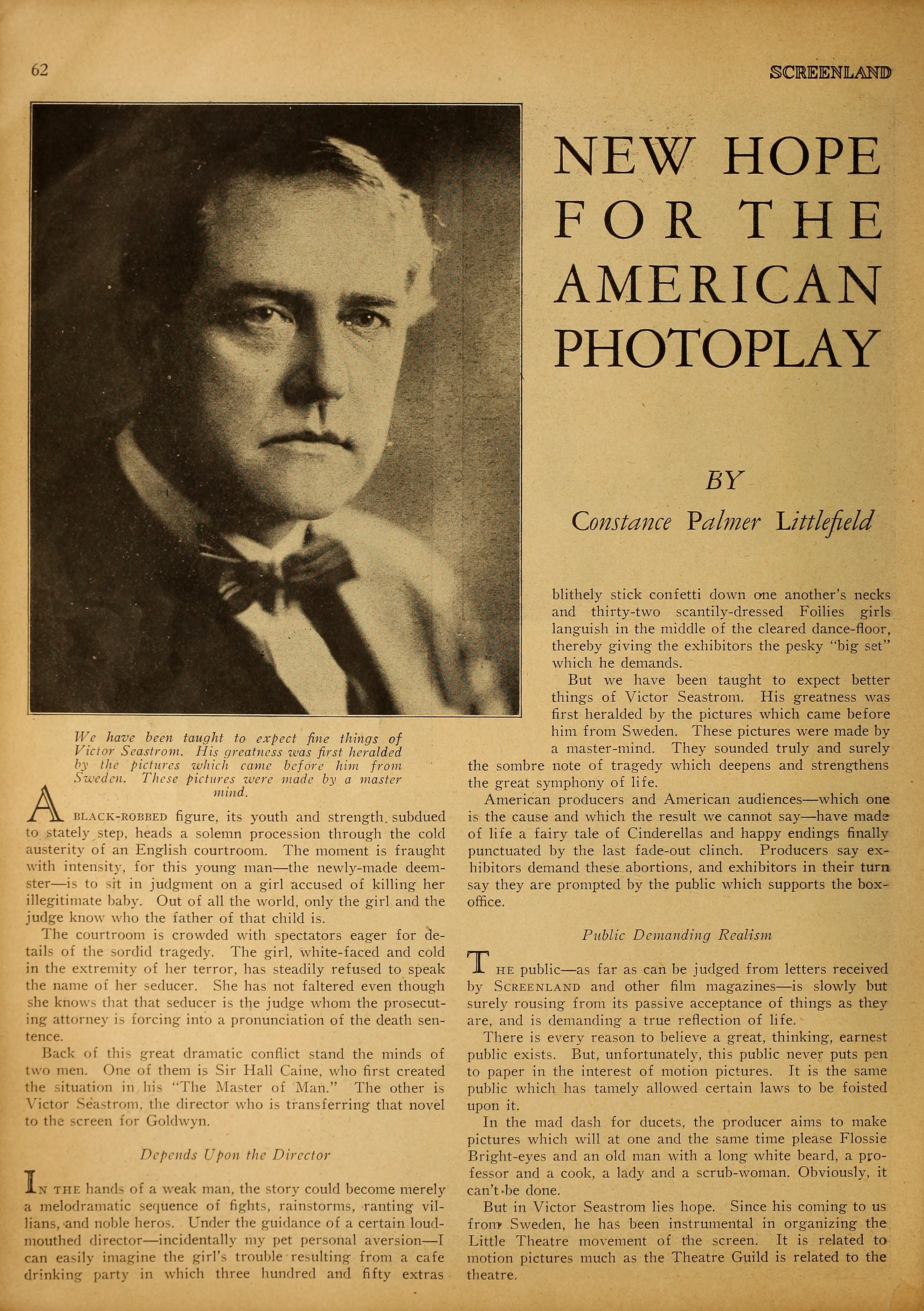

But we have been taught to expect better things of Victor Seastrom. His greatness was first heralded by the pictures which came before him from Sweden. These pictures were made by a master-mind. They sounded truly and surely the sombre note of tragedy which deepens and strengthens the great symphony of life.

American producers and American audiences — which one is the cause and which the result we cannot say — have made of life a fairy tale of Cinderellas and happy endings finally punctuated by the last fade-out clinch. Producers say exhibitors demand these abortions, and exhibitors in their turn say they are prompted by the public which supports the box-office.

Public Demanding Realism

The public — as far as can be judged from letters received by Screenland and other film magazines — is slowly but surely rousing from its passive acceptance of things as they are, and is demanding a true reflection of life.

There is every reason to believe a great, thinking, earnest public exists. But, unfortunately, this public never puts pen to paper in the interest of motion pictures. It is the same public which has tamely allowed certain laws to be foisted upon it.

In the mad dash for ducets, the producer aims to make pictures which will at one and the same time please Flossie Bright-eyes and an old man with a long white beard, a professor and a cook, a lady and a scrub-woman. Obviously, it can’t be done.

But in Victor Seastrom lies hope. Since his coming to us from Sweden, he has been instrumental in organizing the Little Theatre movement of the screen. It is related to motion pictures much as the Theatre Guild is related to the theatre.

Little Theatre Film Movement

The aim of the organization is to provide, through existing little theatre groups, university dramatic societies and women’s clubs, a practical release for those artistic films which cannot find a place in the commercial theatre,” its announcement states.

The first film scheduled for release by this organization is Mortal Clay, a picture which Seastrom made in Sweden.

The movement is still in the process of formation. It is independent in that one studio contributes no more toward it than another. Yet it so happens, that practically every large company contributes one or more of its big names to the list of sponsors.

For instance, Rex Ingram, Ernst Lubitsch, Hugo Ballin, Paul Bern and Rob Wagner are a few of the men interested. Outside the industry, the Federation of Women’s Clubs for Southern California, the Juvenile Protective League, the Friday Morning Club and the National Board of Review all sponsor the cause.

High Purpose of Idea

Those who have investigated the purposes of the Little Theatre movement in pictures have every faith in its ultimate success. With these brains behind it, and its first release Mortal Clay, it will have a good start on the road. Once started, all it will need is support — yours.

The editor of Screenland wired me to ask Mr. Seastrom for his views on “What is the matter with American photoplays?” But after talking with persons who knew the director well, I decided that discretion was the better part of valor. He is, it seems, very bashful with interviewers and very reticent in his expressions of opinion regarding American films. The method of approach, therefore, had to be roundabout.

I found him in the stone court-room I have described. He is a tall man, strongly built. His eyes are typically Nordic blue — the blue of the winter sea, and his voice, soft now, gives suggestion of great strength and volume. In fact, latent strength is the keynote of his character. One can see it in his hands, in his every move.

Difficult to Interview

I cudgeled my brain for the opening question. This is all-important, for by it, the interview” may freeze his victim into ice on the instant.

They had planned that I talk with him at lunch, but at noon, when they approached him on the subject, I could see him shaking his leonine head vigorously, something like terror in those sea-blue eyes. I thought, with an irreverent inward giggle, of the terror of an elephant for a mouse.

At last they persuaded him to remain cornered for a very few minutes.

Now for my carefully-couched question!

“Would you mind telling me, Mr. Seastrom, a little of how they make pictures in Sweden? Is the industry on as large a scale as it is here?”

“Well —” and this strong man actually faltered, choosing his words oh, so carefully. “It is quite large.”

Not so good on that one, but an opening at least.

“Is there as much money invested there as there is here?”

“Ye-es there is a good deal of money in pictures there.”

Not so good.

“Are pictures in Sweden backed by independent capital? Is the industry made up of independent producers?”

Swedish Film Trust

“No, not exactly. It is more like a trust.”

Ah ha — an admission! Poor man — he had fallen into the trap!

“But aren’t there anti-trust laws there, as there are here?”

“Oh, yes, — but there are always ways, you know,” smiling apologetically.

So much for that. Well —

“Are the studios as large as they are here?”

“Yes, they are quite large. Maybe not so large, though.” (Yes, we have no bananas, I thought.) “Maybe not so large as Stage Six.” You have all heard of Goldwyn’s Stage Six, the largest in the world. “Maybe as large as this,” he waved his hand inclusively at the courtroom, which is not large as sets go.

Evidently, “stage” as picture fans understand the word, means “studio” in Sweden.

“How about working facilities?”

One-Man Pictures

We have not so many as here,” he said more positively. “One has no assistants there. One does all oneself.

“How about lights — how is location work managed?”

“We have fine lights, too. You see we work only in summer because the theatres close and the actors come direct from them to the studios. There are no actors who give their talents solely to the screen.”

“Is the stellar system practiced in Sweden.”

“No — oh, no, indeed,” further warmth and interest. “We do not believe in that. The same actors appear in all the pictures made by the producer. Yes — a stock company. It is like one big family.” Again the smile. “One is very happy to work with them.”

But in spite of the smile, I could see him becoming more and more restive. I could not find it in my heart to torture him longer. He was so obviously unhappy. I intimated that he was released.

“Oh, — thank you!” and before I could turn to him from a glance about in search of my guides, he had vanished. Whether he had flown through the ceiling or had disappeared into thin air, I know not.

Vast Knowledge of Life

I do not think I am poking fun at Victor Seastrom. Far from it. My life as an interviewer has been made up of such a large number of things, that I have honest liking and gratitude for this particular variety of victim. When one realizes the past achievements of the man — realizes the nice application of his vast knowledge of life and acting to the work at hand, it is astounding to find such reticence.

Poor, unhappy man! He is doomed to many an uncomfortable hour, for the world within the next year will send many and many an interviewer to talk with him — not about ships and sealing wax — but about Victor Seastrom, his one poor subject of conversation.

So, if we are to learn his views on American photoplays and photoplay-making, we must reconstruct them from the few remarks recorded on these pages.

Therefore, at the risk of incurring his righteous wrath, I shall make so bold as to give you his views as I conceive them:

He — quite naturally — likes to make pictures better in Sweden than he does here. You can’t blame him. Then he is among his people, speaking his tongue, basically thinking his thoughts. His mind is Swedish and his pictures appeal first and foremost to Swedish minds.

Great Technical Opportunities

“But America gives him greater technical opportunities for the making of pictures — providing the American public will accept them. That is the chance he is running now. In all probability, the thought which is uppermost in his mind during these days of filming The Master of Man is:

“Am I making a picture which the American mind will embrace? Will each and every scene in this picture be clear to the American public?”

I sensed that he regretted having said that Swedish motion pictures were controlled by a trust. The remark oozed out, as it were, and was quickly repressed. But here, perhaps, is another reason why Seastrom is making pictures in this country. It is possible that he was restricted too much by this combine, and feels that America is the promised land, in that respect at least.

Short Picture Making Season

Then, too, the time allotted to Swedish picture making is short. A few brief months in the summer and — pouf! it is over.

We are all awaiting eagerly the release of both Mortal Clay and The Master of Man. These pictures, made under varying circumstances, in two different countries, will offer food for comparison. By them we can learn the relative merits and demerits of the native and the foreign branches of the industry. In other words, we will see what America has done for or done to Victor Seastrom.

I prophesy that the world will soon recognize him as the greatest director in motion pictures.

We have been taught to expect fine things of Victor Seastrom. His greatness was first heralded by the pictures which came before him from Sweden. These pictures were made by a master mind.

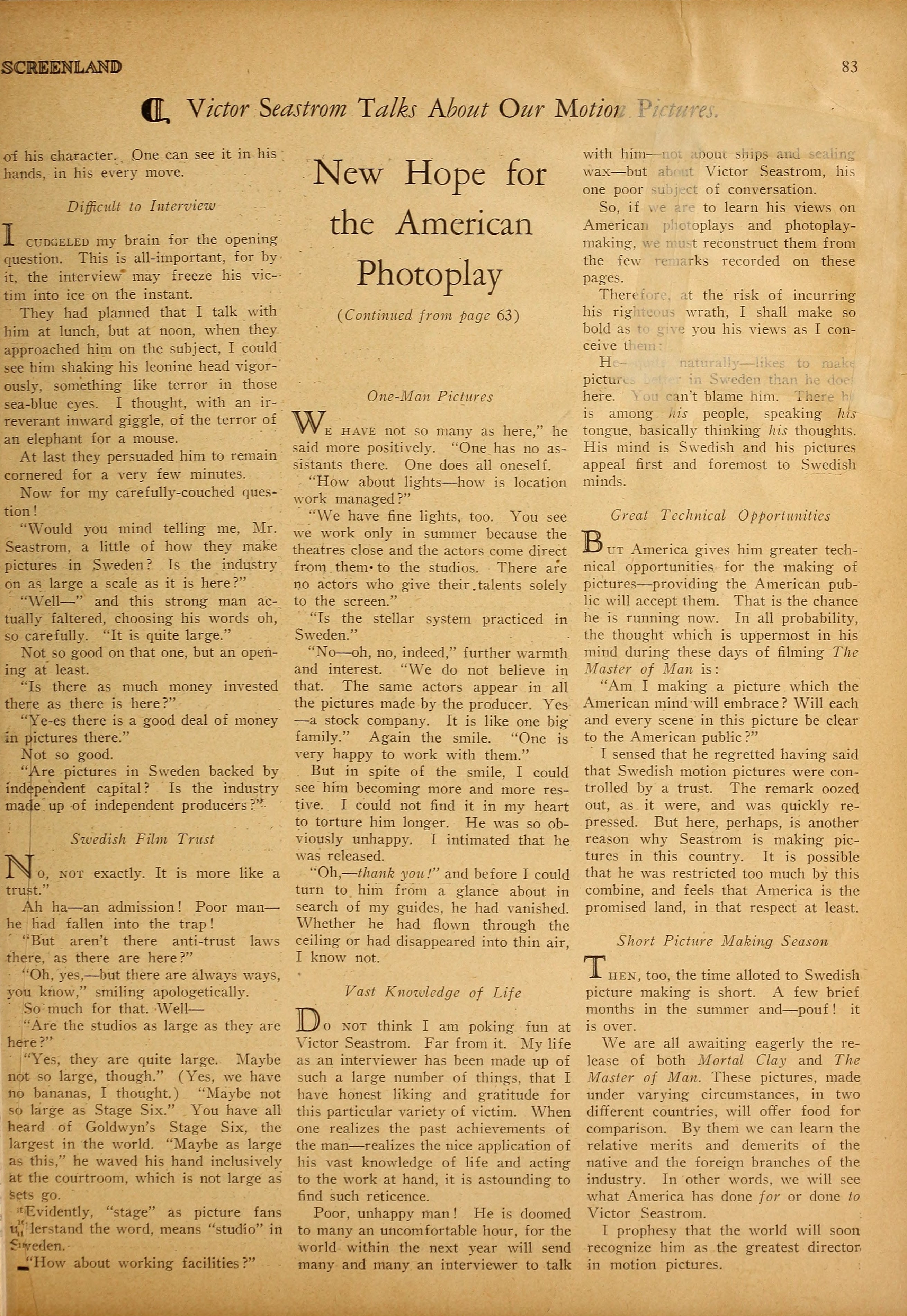

Victor Seastrom and his cameraman, Charles Van Enger, “shooting” a scene of The Master of Man.

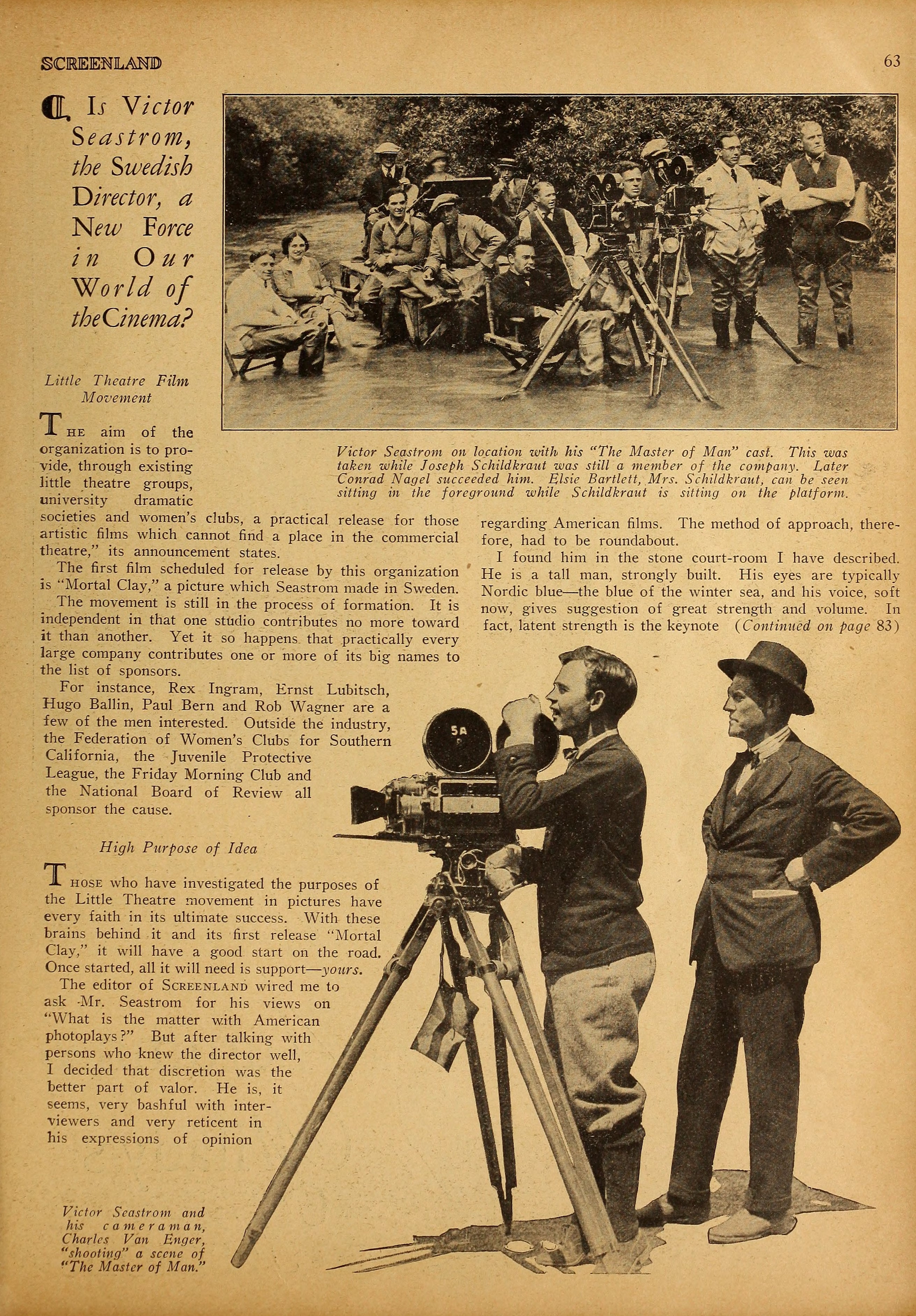

Victor Seastrom on location with his The Master of Man cast. This was taken while Joseph Schildkraut Sr. was still a member of the company. Later Conrad Nagel succeeded him. Elsie Bartlett, Mrs. Schildkraut, can be seen sitting in the foreground while Schildkraut is sitting on the platform.

Collection: Screenland Magazine, October 1923

---

see also Victor Seastrom — The Sombreness of Seastrom (1925)