Our Chinese Movie Actors (1926) 🇺🇸

The Orientals who take part in our movies are just as ambitious for screen success as any of our American players. This story reveals some interesting things about some of them.

by A. L. Wooldridge

There is something strangely fascinating about a city’s Chinatown. One unconsciously thinks of it in terms of shadows, dark passageways, quaint little red-and-yellow lanterns, funny little gods graven in ivory and ebony, and the pungent odor of burning joss sticks. Then there’s the whine of the strange reed flute, the beat of tomtoms, the faint, mysterious shuffling one hears behind closed doors. It usually savors so of the Orient, and we don’t know much about the. Orient. Perhaps that’s why it fascinates.

I recall quite distinctly the eagerness with which I looked forward to my first trip into the famed Chinatown of San Francisco, that picturesque Oriental quarter reached by Grant Avenue slanting away from Market Street. I joined the throng of tourists there some years ago, and went into another world, one where great stone and granite buildings gave way to pagoda-shaped structures, done in gilt and ornamented with dragons, where glaring arc lights were displaced by multicolored lanterns, and where the streets were narrow. I wandered for hours, with the other rubber-neckers, amid the odd little shops and curio stores, and bought a good luck charm which I carried till sonic one stoic my overcoat. It was in one of the pockets.

I found the same alluring interest, though to a lesser degree, in Los Angeles, when I went in search of Tom Gubbins, the “Boss of Chinatown” in that city. He supplies the Oriental characters for motion pictures in Hollywood. There, in Los Angeles, were the same little shops, the same little curio stores, and grocery cubby-holes, where strange fishes and foods were for sale midst the same Oriental setting. Chinatown everywhere is much the same. And there was Tom Gubbins, a highly educated, courteous, gentlemanly individual still in his thirties, who lived for eight years in China and who speaks that peculiar language. He has at his beck and call about a hundred and sixty Chinese men, women and children, who work in pictures and for whom he makes all contracts and engagements. He gave Anna May Wong her first work as atmosphere in a Hollywood production, and now has two of her sisters seeking careers. For the past decade, he has guided the destinies of these Chinese players, and understands their Oriental turn of mind. He acts as interpreter-director on the set.

“My Chinese are trying hard — very hard — to win the respect of Americans,” Gubbins says. “They do not like to appear in roles which in any way seem degrading. Honor and honesty are characteristics of their race. For example:

“When we were working in the William Fox production ‘Shame,’ directed by Emmett Flynn, the script called for scenes in an opium den. The action revolved about some low-caste Chinese characters and led to one of those dives where, in fiction, white girls become slaves of a fearful drug and are ruined.

“Do you think the Chinese would appear in those scenes? Not on your life! When they found out what was to be filmed, they began moving away. Called to go on the set, they would not budge.

“‘No, Mis’ Gubbins,’ the leader said. ‘Him blad. We no want play.’

“They chattered among themselves, shook their heads, backed off. It looked like mutiny. Then I was called, and I had to take great pains to explain that though the scene showed an opium den, the action would teach a splendid moral lesson, and that it was their duty to help teach this lesson. I had to tell the whole story to them, and it was only then that they would consent to go ahead. At that, they didn’t like it and very plainly told me that they wanted no more of that kind. It tended to degrade the Chinese.

“And they also let it be known that they would take part in no scenes which showed Chinese kidnaping white girls. You remember, back in the old days of serials, the spectacle of the heroine being snatched by villainous Orientals and dragged into a den of vice. It was quite common. The truth of the matter is that fewer white girls have been attacked by Chinese than by any other race of people, and yet writers seem to delight in describing scenes in which young women are forced into underground dives and gloated over by Celestials. I do not believe any persuasion could make my players appear in such a play. It would raise such a storm of protest among their countrymen that their lives might be in danger. They simply wouldn’t do it.

“As I said, the Chinese believe in honor and honesty. When we were making Eve’s Leaves for Cecil B. DeMille, Leatrice Joy and Robert Edeson were playing with a soon poon, a sort of counting machine on which buttons are strung. Moving certain buttons on certain parallel wires served to solve problems in addition. Miss Joy worked laboriously at the task, endeavoring to help her father (Edeson). Then, suddenly tiring of her effort, she dashed the whole calculation into a jumble. All the work was ruined. The play called for her to receive a severe reprimand.

“But, in the eyes of the Chinese, do you think she would get it? Not a word!

“‘No!’ they said. ‘Reprimand father — not her. He to blame for raising girl with such temper. He wrong.’

“Chinese justice!

“Their ideals and their faiths and their fidelity have been handed down through generations. There is no more loyal race in the world. Take the case of Choy Sook. When we were making East of Suez, he took a fancy to Director Raoul Walsh and Pola Negri. Every day he used to bring Mr. Walsh some little present — a trinket, a symbol, or a Chinese emblem. He gave Miss Negri an odd little charm which had come to him from his grandfather. It was supposed to keep the evil spirits away, and was really something of intrinsic value.

“One night, as Choy Sook was leaving a theater, he was struck by a street car and badly injured. An ambulance rushed him to the receiving hospital, where it was determined an operation was the only means of saving his life, and even so, he had but a small chance. As they placed him on the table, Choy looked up at the surgeon and said:

“‘You tell Dlectah Mis Walsh floh me, I go clear path, makee it leasy floh him when he come. Tell him I say goo’-by.’

“Choy Sook died on the operating table, faithful in his devotion.”

Mr. Gubbins turned to chatter a few words in Chinese to some young men who had gathered. He instructed several to show up at a studio at eight o’clock the following morning. He answered the telephone in English, then talked in the language of the Orient. Half a dozen callers were instructed to sit clown and wait.

“My regret is that there are not more opportunities for the Chinese in pictures,” he resumed. “There are Oriental girls as pretty, from our point of view, as the girls of any country on the globe. And they are ultra-flappers in every sense of the word — bobbed hair, rouged cheeks, carmined lips, French heels, and all that. I regret to say that they are growing away from the ancient Chinese custom and belief that girls should stay at home. Instead, they are working, in stores and ‘going out’ and becoming ‘flappers.’ Pretty! They don’t make girls any prettier! And they like to be stared at just as thousands of American girls like to be stared at. They are modern maids.

“We have one girl, Elena Juarado, half-caste Chinese and Filipino, who, I believe, has as great or greater talent than Anna May Wong. She had a bit, the part of a maid, in The Ten Commandments, and has been called for many other pictures. If she gets the chances that came to Anna May, she will, in my opinion, surpass any work that has been done in the movies by any Chinese actress. But there is the question of race. Were she white, she would be starring now. We have May Louie, an eighteen-year-old girl who played a bit in Mr. De Mille’s ‘Eve’s Leaves,’ and who, in time, is destined to come from obscurity. She has talent, is energetic and ambitious.

“Mary Wong, sixteen, a younger sister of Anna May Wong, is trying hard to carve out a career in the movies. Lulu Wong, another sister, about twenty, has been in pictures for seven or eight years. Virtually all Chinese girls want to get into the movies, as do the young men. However, there is not enough work to keep them regularly employed, and they must find something else to do. I should like to bring down from San Francisco, and show to the world, some of the pretty Chinese girls there, and I may do it some time. It would be quite a revelation in beauty.”

Contrary to general belief, the Chinese do not want to do plays based on ancient religious beliefs, Mr. Gubbins says. “In fact,” he adds, “they are the least religious people in the world. They are selling their gods to curio seekers, and worshiping almost nothing. The Chinese Temple in Los Angeles is almost totally unattended. The Chinese are becoming worldly. It may surprise you to know that they want to play comedy roles, and do the dramatic. We have Willie Fung, for instance, who weighs a hundred and eighty pounds and is a sort of second Roscoe Arbuckle [Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle] — or as nearly as he can be. First National gave him a small part in one of its recent plays.

“Then we have Chan Lee, who might double for Ben Turpin. He is about the only cross-eyed Chinese I ever saw. Chan clerks in a store most of the time, but he has played in pictures at Mack Sennett’s with Harry Langdon. He has a comedian’s talent.

“And I must tell you about Ng Ming! He won’t go to see any picture at all except those made by Tom Mix. Then he comes back and tells you all about what Tom said and what Tom did, and imitates his actions so vividly that he’s a scream. We call him Tom Mix, and it makes him get chesty! He doesn’t try to ride a horse as Tom rides Tony, but he does most everything else.

“One of our most widely known players is Jimmie Wang [James Wang], who has appeared in a lot of pictures. He went to Tahiti with Maurice Tourneur, and to Canada with Reginald Barker. Jimmie formerly was a Baptist minister in Boston. He came here seven or eight years ago with the idea of becoming a motion-picture actor — believed that any one who could be a successful preacher could be a successful actor. And he certainly made good.”

Probably the most widely known Oriental player in motion pictures is So Jin [Sōjin Kamiyama], a Jap. He was born in Sendai City, Japan, the son of a doctor who had been a member of Parliament. His ambitions, since childhood, have been literary, and while attending school and college, he wrote several volumes of poetry. He studied at Waseda University, Tokyo. Upon his graduation, he entered Tokyo Fine Arts College, and studied painting. He became interested in drama at this time, and before finishing his course, entered Bungei Kyokai (The Literature Arts Association), presided over by old Professor Tsubouchi, outstanding dramatist of Japan.

So Jin then took up dramatic work in earnest, and after learning a great deal from Tsubouchi, established a stock company of his own. It was necessary for him to train his own actors before they were sufficiently at ease for stage appearances. Then he produced classical and modern plays in Japanese for some time, presenting the works of Shakespeare, Goethe, Ibsen, Tolstoi, Shaw, Oscar Wilde, and others. For ten years, he was considered the leading director and actor of Japan.

Six years ago, So Jin left Japan for Hollywood, intending to study motion-picture production. He was unsuccessful at first, and went to San Francisco, where he established The East and West Times, a Japanese publication. He visited some Japanese friends in Los Angeles, and was fortunate in meeting Douglas Fairbanks [Douglas Fairbanks Sr.], who happened to be looking for Oriental characters for The Thief of Bagdad. He was given a big part in this production, and has been in demand ever since. “East of Suez,” “The White Desert,” Proud Flesh, The Wanderer, The Sea Beast, and The Bat, are among the productions he has appeared in.

The younger generation of Chinese in America are growing up in the atmosphere of American ideals, Mr. Gubbins says, and their ancient customs are disappearing.

“When we had the call to the DeMille studio recently,” he said, “a restaurateur came to me and said:

“‘I wish you would send as many players as possible to my place of business at lunch hour. I can serve chop suey, rice cakes, and all the Chinese dishes.’

“‘You can?’ I inquired. ‘Chop suey is an American dish — not known now in China. Do you know what they want to eat? Ham and eggs!’”

Chinese players welcome a film like “Eve’s Leaves,” for it offers many of them jobs. May Louie, talented bit player, is in the center of the scene above.

Lulu Wong, sister of Anna May Wong, is ambitious to equal her sister’s fame.

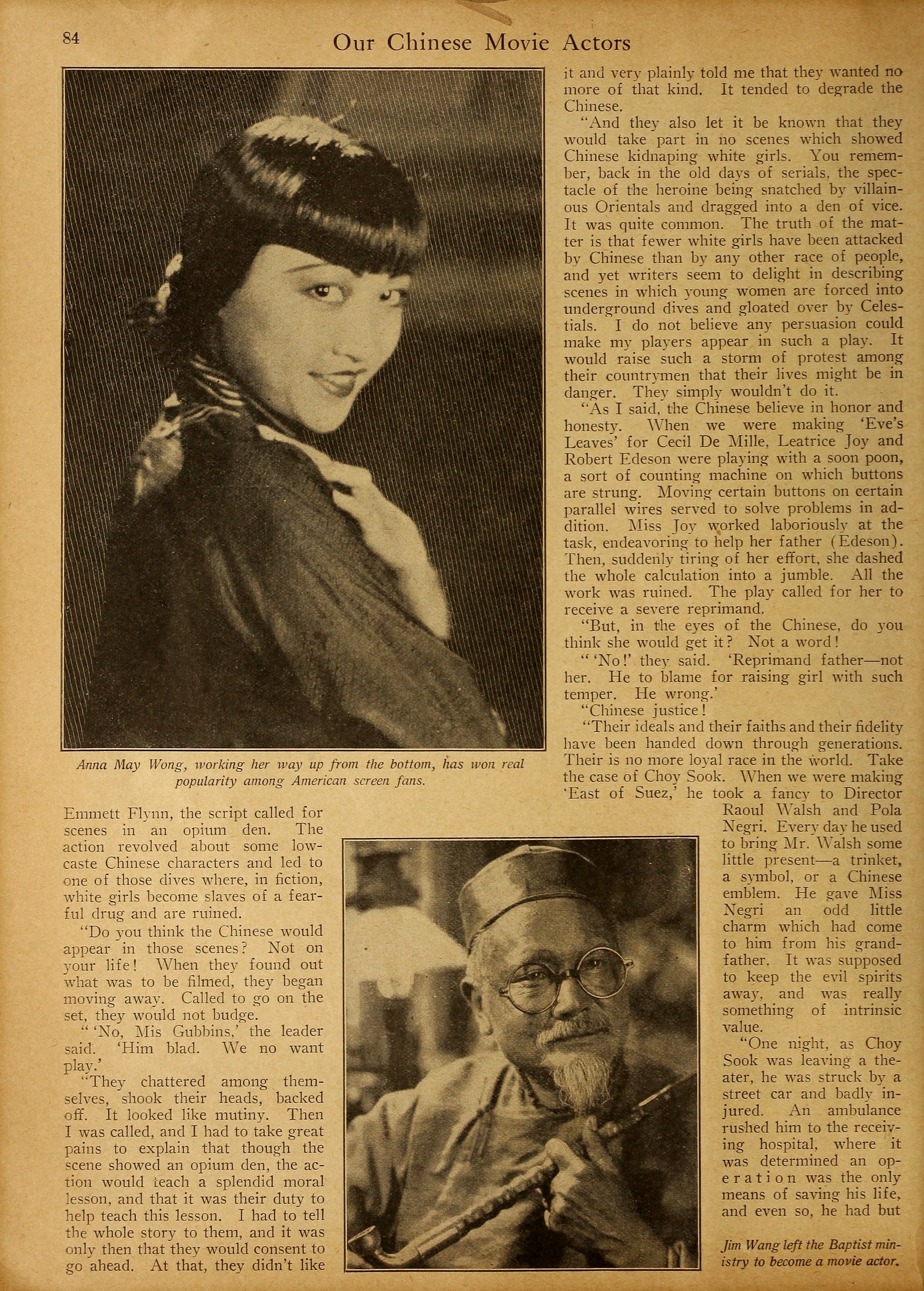

Anna May Wong, working her way up from the bottom, has won real popularity among American screen fans.

Jim Wang left the Baptist ministry to become a movie actor.

Probably the most widely known Oriental player on the American screen is So Jin, the seated figure above, as he appeared in The Thief of Bagdad.

Willie Fung aspires to be a comedian.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, September 1926