Nancy Carroll — The Littlest Rebel in Hollywood (1929) 🇺🇸

“My life didn’t begin until I married,” says Nancy Carroll. “Before that it was just nothing. I was but half a person. Now we are together. We hold “the fort for each other.”

by Elinor Corbin

But it was that life before her marriage that gave Nancy that wonderful courage of hers. It was when she was a little two-fisted Irish girl on Tenth Avenue, New York, that she began to wonder. What did she want? What did she want of life? She didn’t really know. She didn’t actually realize what she was seeking. But she had taken the first step. She knew what life wasn’t.

It wasn’t bending over a typewriter in a big factory under a dead blue light in a room with a hundred other girls trying to answer a letter from a lady in South America who seemed to want a pair of pink slippers. It wasn’t going from one firm to another, getting fired as quickly as she got a job because she was only thirteen and didn’t have her working papers.

And, although she liked her employers, Urchs and Hegemer, it wasn’t being private secretary in their lace company. Life was something more gallant; Life had more spirit.

She was, like every other red-headed Irish girl her age, stage struck. Her family were all talented.

There were, in all, fourteen children. Nancy was the seventh child of a seventh child. Only eight are now living, Martin, Elizabeth, Sarah, Teresa, Tommy, Nancy, Johnnie, Elsie. It was a bright, laughing, Irish Catholic family, with big Thomas Lahiff, their father, at the head of it. Tom Lahiff played the concertina. Their mother told the children that’s why she married him. All the kids inherited laughter from him and played the piano and sang and danced.

But Nancy’s hopes of entertainment went beyond family gatherings.

It all began in an amateur way.

Nancy and Teresa worked up a little sister act. They crooned and harmonized popular melodies and, unknown to their mother, tried out at one of the vaudeville houses. They heard of a theater on the East Side, sufficiently far away from the disapproving parental roof. They were from the West Side and had no right to be there, but a friend, Buddy Carroll, told them to say they were his sisters and to give his address as theirs. And so they became Nancy and Terry Carroll.

They became sort of professional amateurs, and went from one local theater to another until various musical comedy impresarios began to call them. George White asked for an interview. And J. J. Shubert. It was the latter who offered them a specialty number in his Passing Show of 1923.

The two sisters huddled in a family conference. Would their mother ever be reconciled to their going on the stage? Would their father allow them another night’s rest under his roof if he knew?

But Nancy was willing to take a chance. As she always is.

Because both girls had jobs as secretaries, Shubert was good enough to let them rehearse at night and they didn’t tell their mother until after dress rehearsal.

When they got to the house on Tenth Avenue their mother was in tears and a fury. She had called the police. She had searched every hospital. They had to tell her that they were on the stage. Dark looks accompanied them to bed.

But publicity won Irish Ann Lahiff. The next day was Sunday and there — right in the rotogravure section of the paper, was a large and beautiful photograph of Nancy.

It was several weeks before she would go to see the show and when she did she sat high in the balcony to watch her daughters. Her only comment was, “Oh, you were very good, very good, but I thought you tossed your limbs a bit too high.”

Still she groped for life. The stage was better than the factory. It was better than being a private secretary, but it was a full, important life she wanted.

She found what was important when she met a young reporter on the New York News named Jack Kirkland. And, when she married him a few months later, she knew that her life had just begun.

She gave up the stage for a while, but went back to it in The Passing Show of 1924.

She danced until four months before her baby was born!

The enforced inactivity bored her. Nancy, who had never been idle in her life, could not be idle, so she talked to Jack’s managing editor, Phil Payne, who went down with “Old Glory.” He let her interview all the actors she knew because she could get past the imposing ogres who guard stage doors.

She interviewed Hal Skelly and Fay Bainter and a number of others and, with Jack’s help, wrote pieces about them for the paper.

Then, quite suddenly, the great idea was born.

They would go to Paris! Nancy would have the baby and Jack would write the Great American Novel.

A baby and a novel in Paris!

They looked at their bank balance. By some mysterious process a thousand dollars had gotten there.

Plenty of money for vagabonds.

Jack told his managing editor that he was going to resign and go to live for awhile in Paris.

“Well, as long as you’re going,” said Payne, “you might as well have a job.”

So the amazing vagabondage was denied them for awhile. Jack was literally handed a position as Tom Mix’s press agent at $350 a week and all expenses paid for himself and his wife.

They lived like kings in Paris.

They entertained all the newspaper men royally at the Ritz bar and then fled to a little restaurant on a side street and pretended that they were poor.

Nancy had thought it thrilling to have her baby born in Paris.

She had even made reservations at the French Hospital, but something American took hold of her and she wanted to be in New York when the great event occurred. They booked passage at once.

Nancy had not thought of a doctor. She went to a fine specialist just a few weeks before the baby was born and he took one look at her, said she was perfect and dismissed her at once.

Patsy was a very expensive baby. After she was born there was no money. So Nancy went back on the stage and Jack took his old job on the News.

Jack worked the graveyard shift. He finished at three A. M. At that time it was the fad for the big musical shows to send acts to the night clubs. Nancy completed the day at three, also.

And they met and found new adventure together.

But Jack, having once touched movie gold, was sick of newspaper salaries. He wanted to go to California.

They adventured to California. Jack found movie gold scarce, so Nancy went on the stage.

She worked in a little musical comedy called Nancy.

Macloon saw her and signed her for three years.

During this time she had dozens of picture tests made. M-G-M, First National, Warner Brothers, Universal — all had her face recorded, but nothing ever came of it. Jack took a place writing for Paramount.

At last a test amounted to something and she did a picture for Fox called “Ladies Must Live.”

But she was tied up on her contract with Macloon and that had to be straightened out before she did “Abie’s Irish Rose” for Paramount and signed a long term contract.

In the meantime she held the fort for Jack. When he went back to New York to do his play, Frankie and Johnnie, she stayed on with Patsy and worked to give him the chance to do it, and when he came back she was happy again.

Nothing really matters as long as the three of them are together.

“Fundamentally,” she said, “I’m an Irish Catholic girl like my mother and if Jack wanted me to stop work and be just a wife and have ten children like Patsy, I’d do it.”

But fundamentally she is a rebel. She gets what she wants by fighting for it. Years ago, when she was a kid she fought with her two fists.

She fought to go on the stage. Now she fights with her mind. Her brisk, humorous, keen mind.

Studio politics worry her not at all.

She knows what she wants. She knows when and how she can do her best work. And she does it.

She is a rebel with her tongue in her cheek. She’s a red-headed, fighting Irish kid with gypsy blood in her veins!

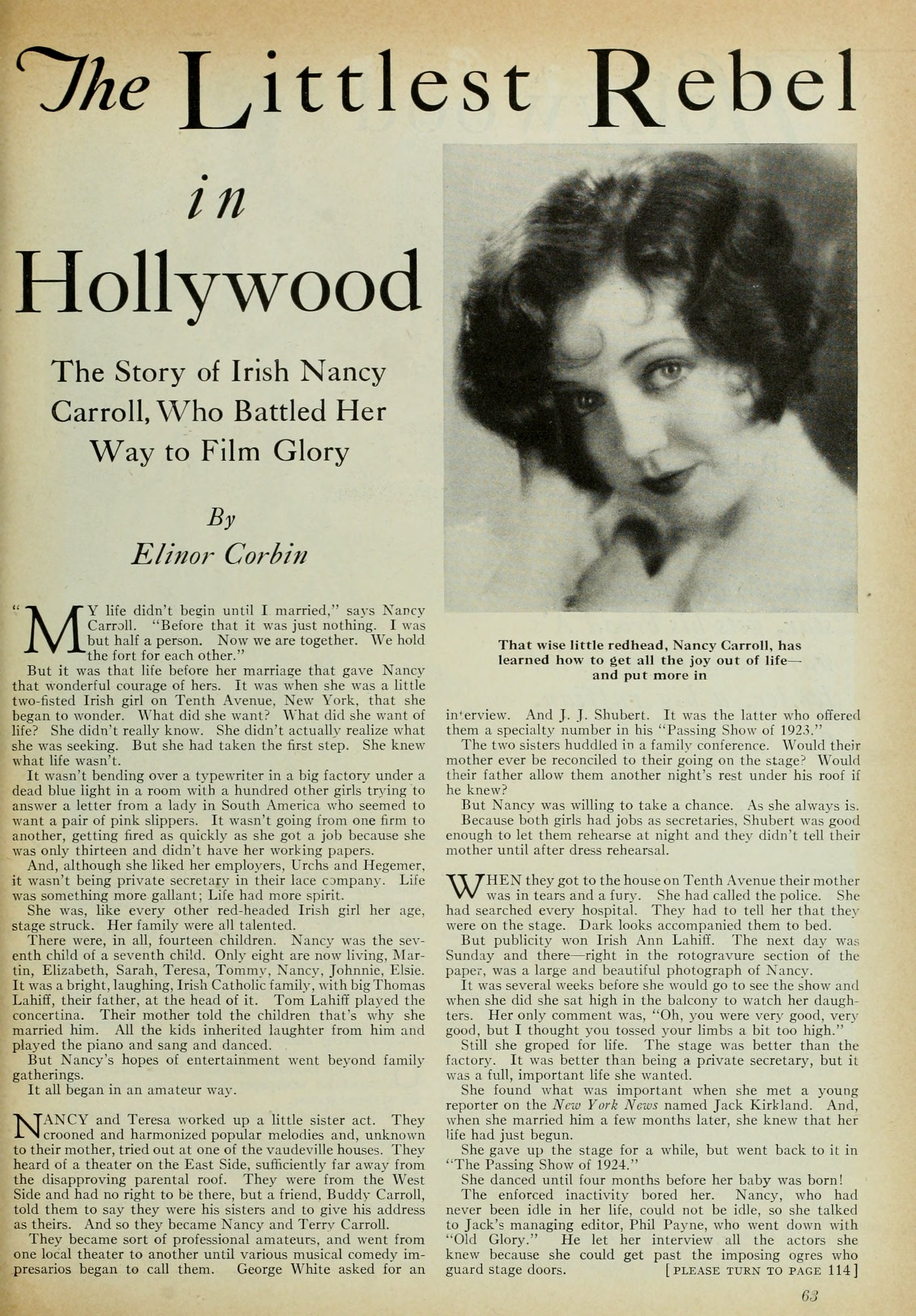

That wise little redhead, Nancy Carroll, has learned how to get all the joy out of life — and put more in

Just a pretty little New York girl, all peaches and cream, whose path led from the Bronx to Broadway to Hollywood and glory. Nancy Carroll, in her new party dress of pointed tulle — no doubt earned by her remarkable work opposite Hal Skelly in The Dance of Life. On the opposite page you will find the smile-compelling, tear-teasing story of Nancy’s rise, starting with the days before she was a little dancer at all!

Photo by: International

Collection: Photoplay Magazine, November 1929