Holbrook Blinn — An Actor of Leisure (1926) 🇺🇸

In this bustling world where the worker reads as he runs and eats standing up half the time, because it takes too long to bother to sit down, it seems incredible that one of the very busiest actors in the world should have as his slogan, “Take your time.” Yet that is just what Holbrook Blinn does say. and not only does he say it, he practices it.

by Dorothy Day

When Mr. Blinn finished his tour with The Dove, visions of four or five months with nothing to do loomed ahead. But the heads of various film companies had other notions as to how he should spend his spare time. His plans for vacationing grew feebler and feebler as one offer after another floated in from the Coast.

Now it is far easier for a child to refuse an ice-cream cone on a summer day than it is for an actor to resist a tempting contract, and gradually Mr. Blinn’s refusals to work became less forceful. “I don’t believe that Jack was a dull boy because he had all work and no play,” he told himself. “He was more than likely a deadly bore, anyway. Besides, it will be fun to work on a picture for a change, after so many months in the theater. It will be just as good, no, better, than a regular vacation.”

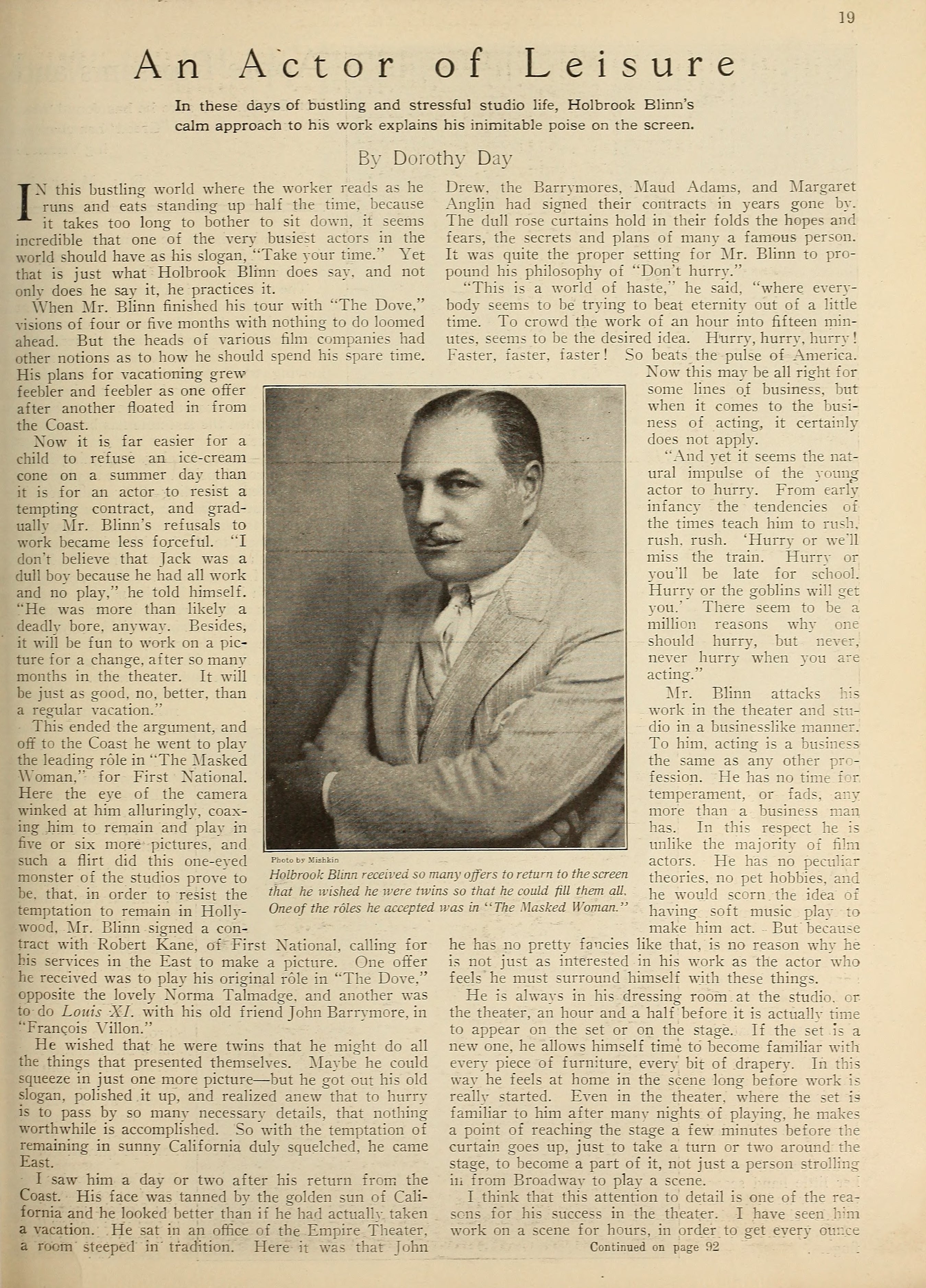

This ended the argument, and off to the Coast he went to play the leading role in The Masked Woman, for First National. Here the eye of the camera winked at him alluringly, coaxing him to remain and play in five or six more pictures, and such a flirt did this one-eyed monster of the studios prove to be, that, in order to resist the temptation to remain in Hollywood, Mr. Blinn signed a contract with Robert Kane, of First National, calling for his services in the East to make a picture. One offer he received was to play his original role in The Dove, opposite the lovely Norma Talmadge, and another was to do Louis XI with his old friend John Barrymore, in François Villon. [Transcriber’s Note: The Dove (1927) — Wallace Beery took over for Holbrook Blinn | The Beloved Rogue (1927) — John Barrymore (François Villon) played opposite Conrad Veidt (Louis XI)]

He wished that he were twins that he might do all the things that presented themselves. Maybe he could squeeze in just one more picture — but he got out his old slogan, polished it up, and realized anew that to hurry is to pass by so many necessary details, that nothing worthwhile is accomplished. So with the temptation of remaining in sunny California duly squelched, he came East.

I saw him a day or two after his return from the Coast. His face was tanned by the golden sun of California and he looked better than if he had actually taken a vacation. He sat in an office of the Empire Theater, a room steeped in tradition. Here it was that John Drew, the Barrymores, Maud Adams, and Margaret Anglin had signed their contracts in years gone by. The dull rose curtains hold in their folds the hopes and fears, the secrets and plans of many a famous person. It was quite the proper setting for Mr. Blinn to propound his philosophy of “Don’t hurry.”

“This is a world of haste,” he said, “where everybody seems to be trying to beat eternity out of a little time. To crowd the work of an hour into fifteen minutes, seems to be the desired idea. Hurry, hurry, hurry! Faster, faster, faster! So beats the pulse of America.

Now this may be all right for some lines of business, but when it comes to the business of acting, it certainly does not apply.

“And yet it seems the natural impulse of the young actor to hurry. From early infancy the tendencies of the times teach him to rush, rush. rush. ‘Hum, or we’ll miss the train. Hurry or you’ll be late for school. Hurry or the goblins will get you.’ There seem to be a million reasons why one should hurry, but never, never hurry when you are acting.”

Mr. Blinn attacks his work in the theater and studio in a businesslike manner. To him, acting is a business the same as any other profession. He has no time for temperament, or fads, any more than a business man has. In this respect he is unlike the majority of film actors. He has no peculiar theories, no pet hobbies, and he would scorn the idea of having soft music play to make him act. But because he has no pretty fancies like that, is no reason why he is not just as interested in his work as the actor who feels he must surround himself with these things.

He is always in his dressing room, at the studio, or the theater, an hour and a half before it is actually time to appear on the set or on the stage. If the set is a new one, he allows himself time to become familiar with every piece of furniture, every bit of drapery. In this way he feels at home in the scene long before work is really started. Even in the theater, where the set is familiar to him after many nights of playing, he makes a point of reaching the stage a few minutes before the curtain goes up, just to take a turn or two around the stage, to become a part of it, not just a person strolling in from Broadway to play a scene.

I think that this attention to detail is one of the reasons for his success in the theater. I have seen, him work on a scene for hours, in order to get every ounce of value out of it. Lesser actors would pass over many little details which he brings out, thus losing much of the flavor that is there. “I have even been called Scotch in my acting,” laughed Mr. Blinn, “because of this desire to squeeze every bit of value from a scene.”

There are very few show places in the East belonging to screen actors, but Mr. Blinn has a home at Croton-on-the-Hudson that would be difficult to rival in the very heart of the film colony on the Coast. It is called “Journey’s End,” and it is a typical farm. The house rambles over a beautiful lawn, which runs off into a lake at the end of it. The place includes acres and acres, and everything in live stock that the proudest farmer would possess. There are pigs, cows, and horses, pigeons, chickens, and grouse. A deer or two wander unmolested in the wooded portions of his estate, and comfort reigns supreme in every nook and corner of the place. It simply knocks to pieces the old theory that you cannot be both grand and comfortable, for there is enough of the modern about it to make it grand, and enough of the real old Westchester farm to give it that comfortable aspect which is usually so sadly lacking in show places.

A quiet day in the country consists of rising at six thirty to fly over the farm in an airplane. You could hardly call this getting back to nature, could you! A dip in the lake before breakfast, a visit to the stables afterwards, and he bids good-by to the peace and quiet of the country for bustle of a day in New York.

“Which do you like best, the theater or the studio,” I asked.

“That is rather difficult,” he replied. “You see, while they may seem different, fundamentally they are the same. For example, would you ask a farmer if he preferred to use a rake or a hoe? Or would you ask a painter if he would rather paint the little villages in Spain or the castles on the Rhine? It is simply a matter of having two mediums for acting, and while there is a difference, a big one, in working before a camera or an audience, still it all comes under the art of acting, and — my goodness! haven’t we been talking about it though?” he finished with a laugh.

And, as no interview is quite complete without a word about Hollywood, I hastened to ask Mr. Blinn how he liked it. I found out that the only objection he has to Hollywood is that it is too far away from New York. “I have a great many friends there, and on the other hand, I have a great many here, so until something can be done about moving the two cities a bit closer together, I shall have to content myself with spending half my time here and half there, and thank the good Lord that it is such a bully old world.”

Holbrook Blinn received so many offers to return to the screen that he wished he were twins so that he could fill them all. One of the roles he accepted was in The Masked Woman.

Photo by: Herman Mishkin (1870–1948)

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, December 1926