Charles Ray — Bucking his Hoodoo (1927) 🇺🇸

Old Man Hoodoo is a funny guy — especially when he mixes up with the stars. Take Charlie Ray, for instance. Remember how Charlie dashed into your ken and mine in The Coward, that day so long ago? How we loved him, how we acclaimed him!

by Grace Kingsley

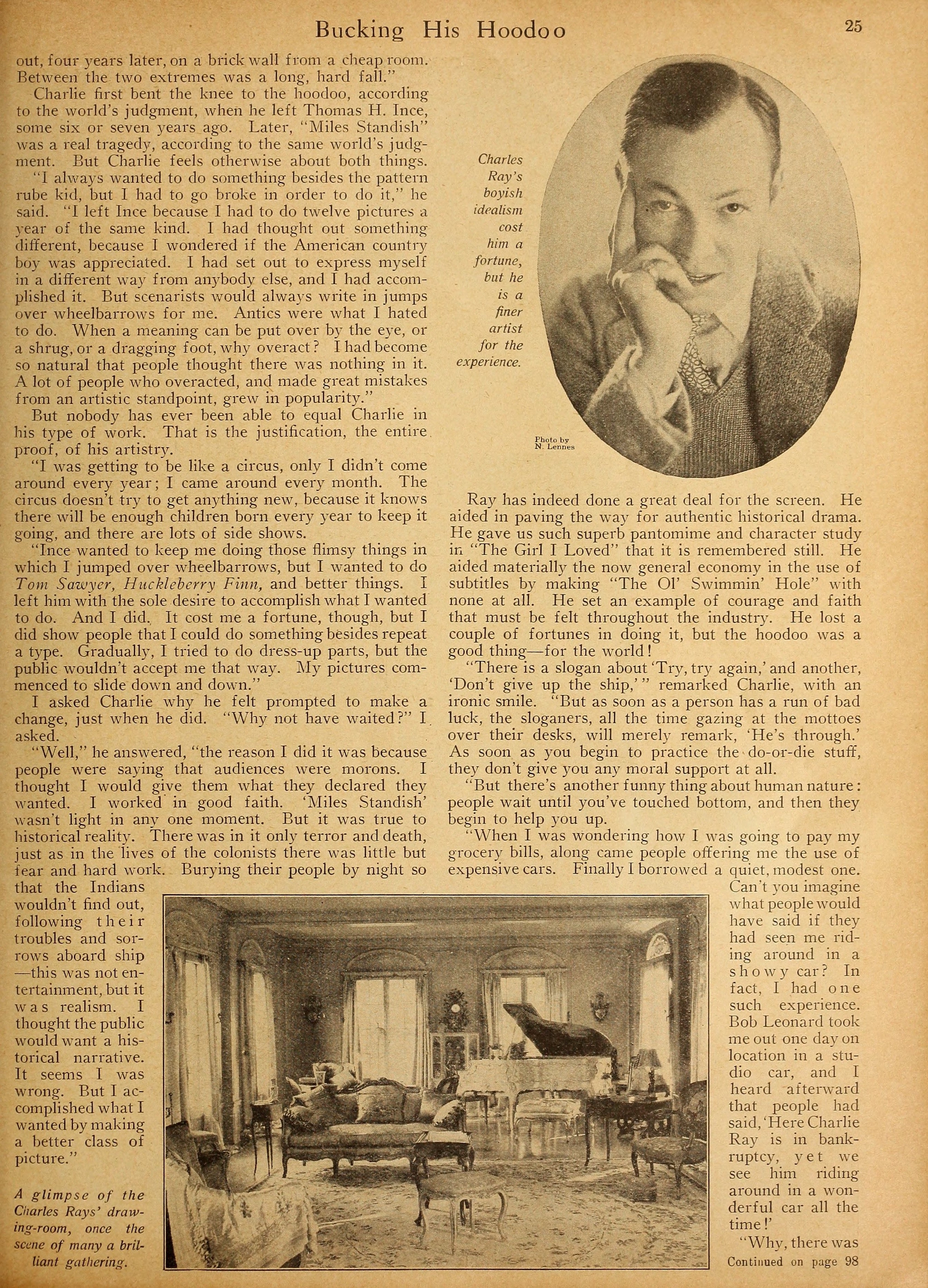

Now Old Man Hoodoo has been claiming Charlie as his own this many a day. Yet Charlie is an infinitely finer actor now than he was before.

For Charlie, in his patient, quiet, thoughtful way, is learning a whole lot from the old man. He may have taken from Charlie his Rolls-Royce, and his home, and a whole fortune or two, but in the still darkness of his night of hard luck somehow the hoodoo has handed Charlie back a lot of gifts in exchange — gifts of a greater artistry, of courage, of fine philosophy, deeper understanding of life, and control of his professional fate by giving him a chance to choose his roles. But perhaps greatest of all is the knowledge that he stands alone in his particular line of work. That’s the way with Old Man Hoodoo. He very often takes with one hand while he gives with the other.

Charlie Ray is never going to be beaten, because he is never going to believe in his own bad luck! For such the old man wears a smile. For such he has gifts.

We talked about it, Charlie and I, in his dressing room not long ago. I noticed he was wearing a three-year-old topcoat. That means a lot. He is paying off his old debts, thriftily, honestly, with self-sacrifice.

“I have had an experience that I wouldn’t give up for worlds,” said Charlie, “although I never would have had the courage to undertake it as a matter of choice. I didn’t get bitter. I used to wonder how people get bitter. Now I know. It is when they accept bad conditions. I never would believe in my bad luck, you see. Accepting or rejecting one’s luck is the business of living. And refusing to accept bad luck has given me so much courage that now I have no fear of lack of money, or of failure.”

With that rare, whimsical, and charming smile of his, Charlie quoted James Whitcomb Riley — “My money isn’t gone. It’s just away!”

It’s not losing money that hurts the most. “People thought it was because I had lost money that I looked so bad in those dark days. It wasn’t the lost money. It was the lost ideals, the not finding in people the qualities I thought were in them, that hurt me most. The money wasn’t so much.

“I saw New York with a million dollars, and later I saw it with a little less than twenty dollars in my pocket — all the money I had in the world. My wife and I had looked out from a front window of an exclusive hotel — and we looked out, four years later, on a brick wall from a cheap room. Between the two extremes was a long, hard fall.”

Charlie first bent the knee to the hoodoo, according to the world’s judgment, when he left Thomas H. Ince, some six or seven years ago. Later, Myles Standish was a real tragedy, according to the same world’s judgment. But Charlie feels otherwise about both things.

“I always wanted to do something besides the pattern rube kid, but I had to go broke in order to do it,” he said. “I left Ince because I had to do twelve pictures a year of the same kind. I had thought out something different, because I wondered if the American country boy was appreciated. I had set out to express myself in a different way from anybody else, and I had accomplished it. But scenarists would always write in jumps over wheelbarrows for me. Antics were what I hated to do. When a meaning can be put over by the eye, or a shrug, or a dragging foot, why overact? I had become so natural that people thought there was nothing in it. A lot of people who overacted, and made great mistakes from an artistic standpoint, grew in popularity.”

But nobody has ever been able to equal Charlie in his type of work. That is the justification, the entire, proof, of his artistry.

“I was getting to be like a circus, only I didn’t come around every year; I came around every month. The circus doesn’t try to get anything new, because it knows there will be enough children born every year to keep it going, and there are lots of side shows.

“Ince wanted to keep me doing those flimsy things in which I jumped over wheelbarrows, but I wanted to do Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn, and better things. I left him with the sole desire to accomplish what I wanted to do. And I did. It cost me a fortune, though, but I did show people that I could do something besides repeat a type. Gradually, I tried to do dress-up parts, but the public wouldn’t accept me that way. My pictures commenced to slide down and down.”

I asked Charlie why he felt prompted to make a change, just when he did. “Why not have waited?” I asked.

“Well,” he answered, “the reason I did it was because people were saying that audiences were morons. I thought I would give them what they declared they wanted. I worked in good faith. Myles Standish wasn’t light in any one moment. But it was true to historical reality. There was in it only terror and death, just as in the lives of the colonists there was little but fear and hard work. Burying their people by night so that the Indians wouldn’t find out, following their troubles and sorrows aboard ship — this was not entertainment, but it was realism. I thought the public would want a historical narrative. It seems I was wrong. But I accomplished what I wanted by making a better class of picture.”

Ray has indeed done a great deal for the screen. He aided in paving the way for authentic historical drama. He gave us such superb pantomime and character study in The Girl I Loved that it is remembered still. He aided materially the now general economy in the use of subtitles by making The Ol’ Swimmin’ Hole with none at all. He set an example of courage and faith that must be felt throughout the industry. He lost a couple of fortunes in doing it, but the hoodoo was a good thing — for the world!

“There is a slogan about ‘Try, try again,’ and another, ‘Don’t give up the ship,’ remarked Charlie, with an ironic smile. “But as soon as a person has a run of bad luck, the sloganers, all the time gazing at the mottoes over their desks, will merely remark, ‘He’s through.’ As soon as you begin to practice the do-or-die stuff, they don’t give you any moral support at all.

“But there’s another funny thing about human nature: people wait until you’ve touched bottom, and then they begin to help you up.

“When I was wondering how I was going to pay my grocery bills, along came people offering me the use of expensive cars. Finally I borrowed a quiet, modest one.

Can’t you imagine what people would have said if they had seen me riding around in a showy car? In fact, I had one such experience. Bob Leonard took me out one day on location in a studio car, and I heard afterward that people had said, ‘Here Charlie Ray is in bankruptcy, yet we see him riding around in a wonderful car all the time!’

“Why, there was a time when I couldn’t even get a job,” said Ray.

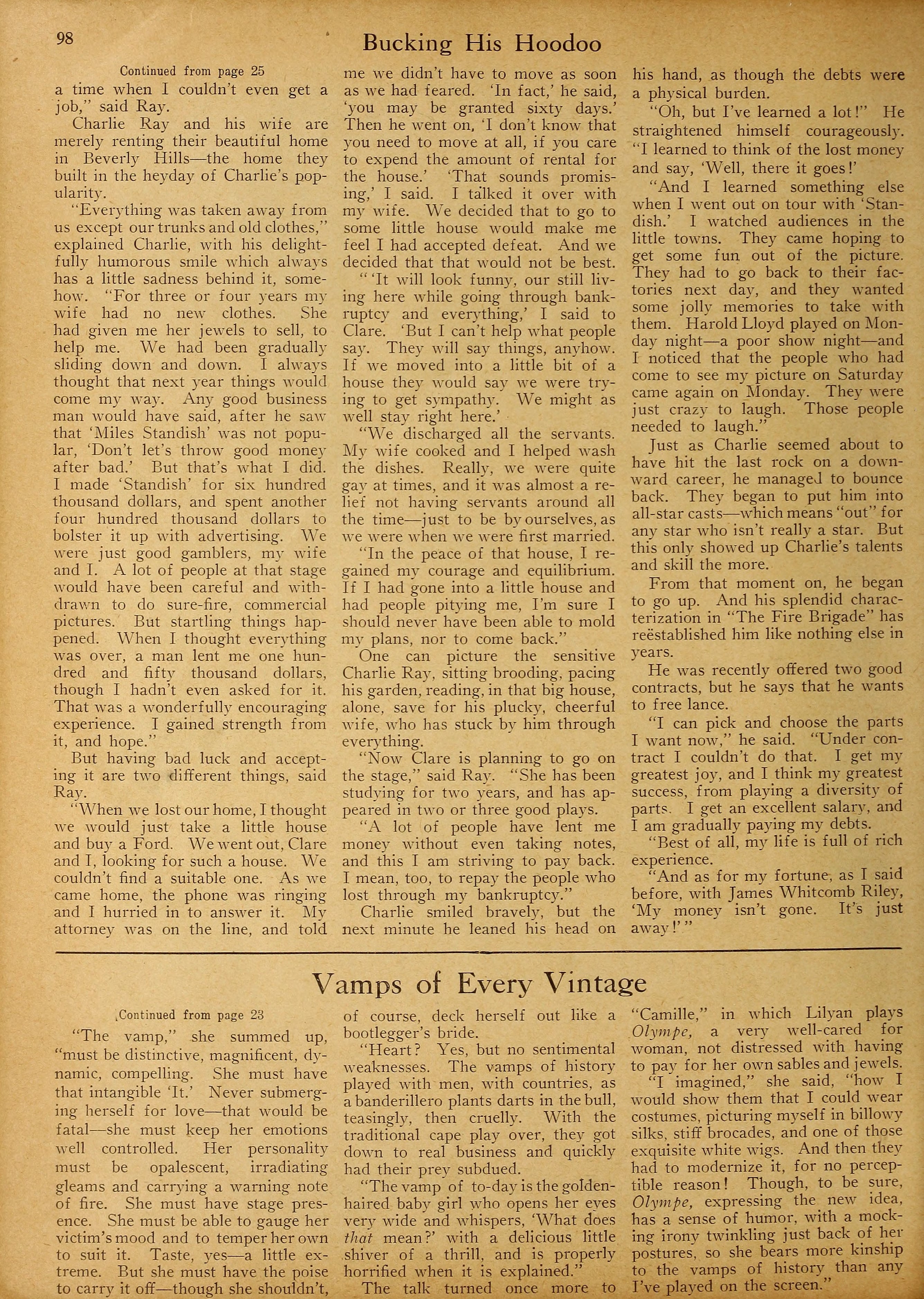

Charlie Ray and his wife are merely renting their beautiful home in Beverly Hills — the home they built in the heyday of Charlie’s popularity.

“Everything was taken away from us except our trunks and old clothes,” explained Charlie, with his delightfully humorous smile which always has a little sadness behind it, somehow. “For three or four years my wife had no new clothes. She had given me her jewels to sell, to help me. We had been gradually sliding down and down. I always thought that next year things would come my way. Any good business man would have said, after he saw that Myles Standish was not popular, ‘Don’t let’s throw good money after bad.’ But that’s what I did. I made Standish for six hundred thousand dollars, and spent another four hundred thousand dollars to bolster it up with advertising. We were just good gamblers, my wife and I. A lot of people at that stage would have been careful and withdrawn to do sure-fire, commercial pictures. But startling things happened. When I thought everything was over, a man lent me one hundred and fifty thousand dollars, though I hadn’t even asked for it. That was a wonderfully encouraging experience. I gained strength from it, and hope.”

But having bad luck and accepting it are two different things, said Ray.

“When we lost our home, I thought we would just take a little house and buy a Ford. We went out, Clare and I, looking for such a house. We couldn’t find a suitable one. As we came home, the phone was ringing and I hurried in to answer it. My attorney was on the line, and told me we didn’t have to move as soon as we had feared. ‘In fact,’ he said, ‘you may be granted sixty days.’ Then he went on, ‘I don’t know that you need to move at all, if you care to expend the amount of rental for the house.’ ‘That sounds promising,’ I said. I talked it over with my wife. We decided that to go to some little house would make me feel I had accepted defeat. And we decided that that would not be best.

“‘It will look funny, our still living here while going through bankruptcy and everything,’ I said to Clare. ‘But I can’t help what people say. They will say things, anyhow. If we moved into a little bit of a house they would say they were trying to get sympathy. We might as well stay right here.’

“We discharged all the servants. My wife cooked and I helped wash the dishes. Really, we were quite gay at times, and it was almost a relief not having servants around all the time — just to be by ourselves, as we were when we were first married.

“In the peace of that house, I regained my courage and equilibrium. If I had gone into a little house and had people pitying me, I’m sure I should never have been able to mold my plans, nor to come back.”

One can picture the sensitive Charlie Ray, sitting brooding, pacing his garden, reading, in that big house, alone, save for his plucky, cheerful wife, who has stuck by him through everything.

“Now Clare is planning to go on the stage,” said Ray. “She has been studying for two years, and has appeared in two or three good plays.

“A lot of people have lent me money without even taking notes, and this I am striving to pay back. I mean, too, to repay the people who lost through my bankruptcy.”

Charlie smiled bravely, but the next minute he leaned his head on his hand, as though the debts were a physical burden.

“Oh, but I’ve learned a lot!” He straightened himself courageously. “I learned to think of the lost money and say, Well, there it goes!’

“And I learned something else when I went out on tour with Standish. I watched audiences in the little towns. They came hoping to get some fun out of the picture. They had to go back to their factories next day, and they wanted some jolly memories to take with them. Harold Lloyd played on Monday night — a poor show night — and I noticed that the people who had come to see my picture on Saturday came again on Monday. They were just crazy to laugh. Those people needed to laugh.”

Just as Charlie seemed about to have hit the last rock on a downward career, he managed to bounce back. They began to put him into all-star casts — which means “out” for any star who isn’t really a star. But this only showed up Charlie’s talents and skill the more.

From that moment on, he began to go up. And his splendid characterization in The Fire Brigade has re-established him like nothing else in years.

He was recently offered two good contracts, but he says that he wants to free lance.

“I can pick and choose the parts I want now,” he said. “Under contract I couldn’t do that. I get my greatest joy, and I think my greatest success, from playing a diversity of parts. I get an excellent salary, and I am gradually paying my debts.

“Best of all, my life is full of rich experience.

“And as for my fortune, as I said before, with James Whitcomb Riley, ‘My money isn’t gone. It’s just away!’”

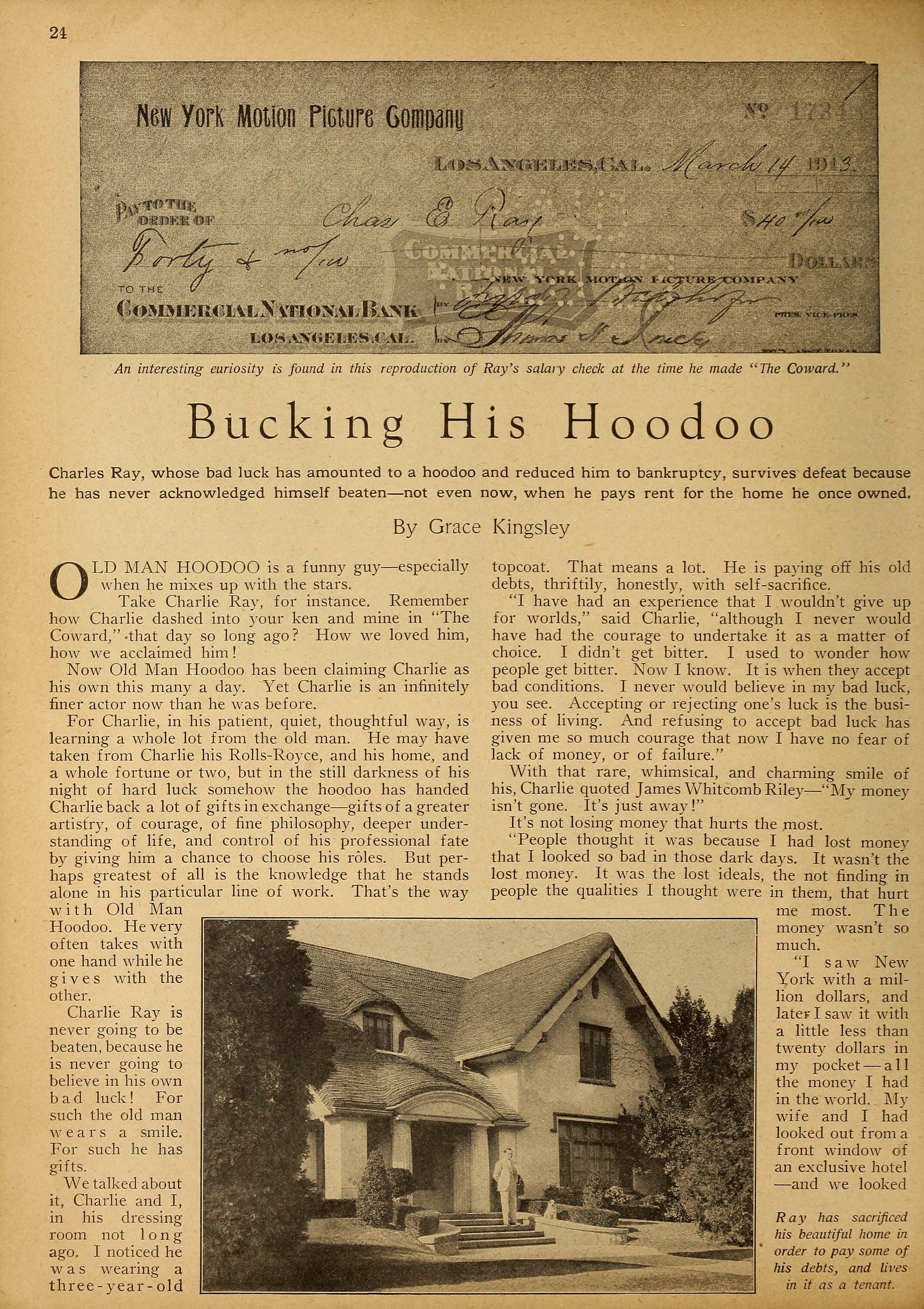

An interesting curiosity is found in this reproduction of Ray’s salary check at the time he made The Coward.

Ray has sacrificed his beautiful home in order to pay some of his debts, and lives in it as a tenant.

A glimpse of the Charles Rays’ drawing-room, once the scene of many a brilliant gathering.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, April 1927