Carol Lombard — A Fire-Alarm Siren (1929) 🇺🇸

When the movies were lisping their first words, an air of chill foreboding developed in the studios — particularly among the beauty squad who had had no stage experience. And even more particularly among the newer players who had not established their names at the box office.

by Louise Williams

Carol Lombard came under both classifications, but she was far from subdued. She didn’t grow wistful or plaintive, nor did she hide herself in quiet corners, there to bleat “mi-mi-mi” in the traditional manner of vocal artists warming up. She strode about the Pathé lot, where she had recently been placed under contract, swaggered into the sound-test room, familiarly known as the torture chamber, and swaggered out again. As the door closed behind her, Carol gave vent to a loud whoop, followed by a whole-hearted laugh that had a ring of triumph in it.

“We dumb artists don’t know what will register on the microphone,” she announced to the morbidly curious who had wondered if perhaps Carol would not be wilted by this crushing experience. “But we’re in good company. None of those experts in there does, either.”

And with that wise pronouncement, she strolled unconcernedly over to her dressing room, answered ten or twelve telephone calls, and made her choice of the suggested diversions for the evening.

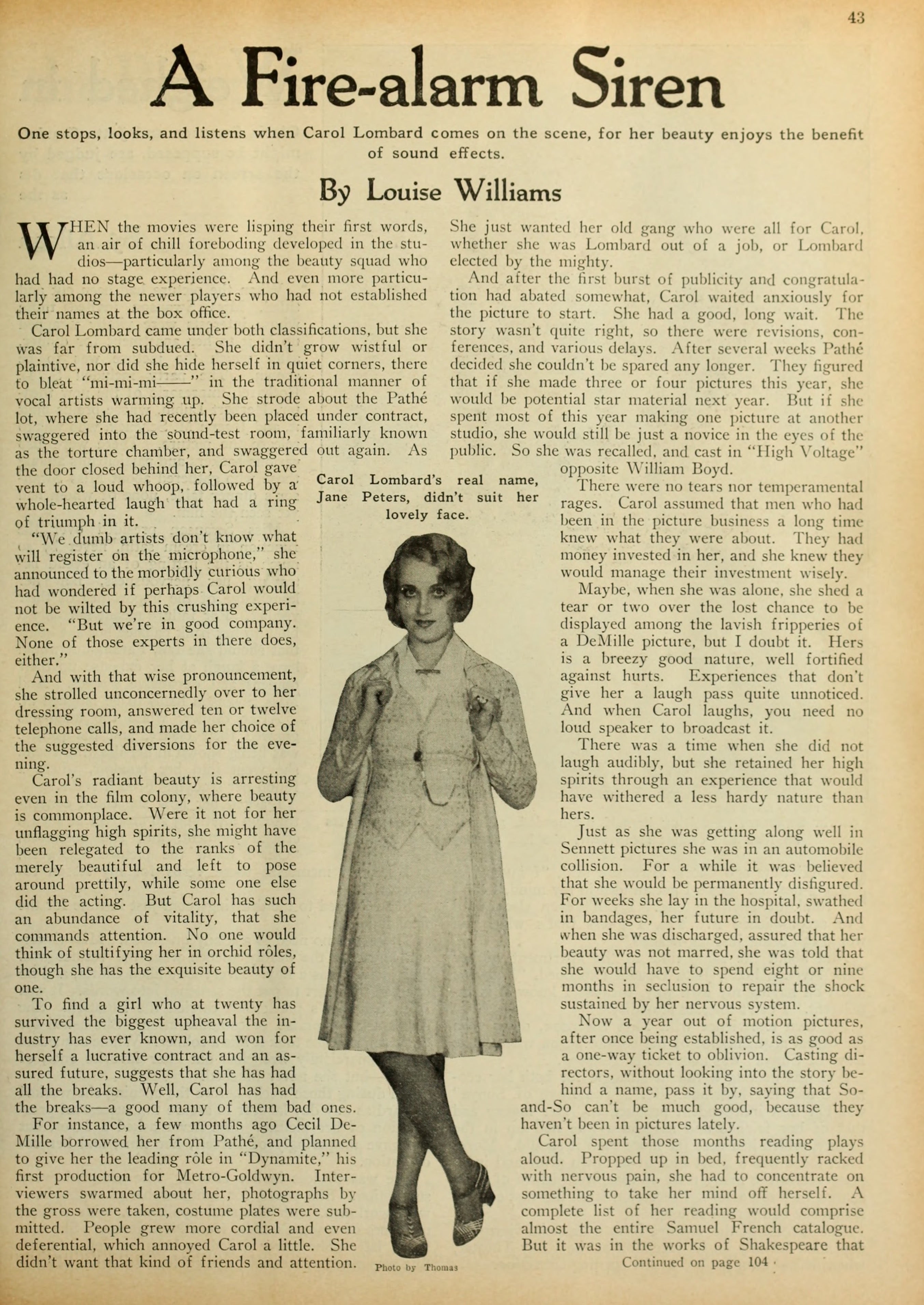

Carol’s radiant beauty is arresting even in the film colony, where beauty is commonplace. Were it not for her unflagging high spirits, she might have been relegated to the ranks of the merely beautiful and left to pose around prettily, while some one else did the acting. But Carol has such an abundance of vitality, that she commands attention. No one would think of stultifying her in orchid roles, I though she has the exquisite beauty of one.

To find a girl who at twenty has survived the biggest upheaval the industry has ever known, and won for herself a lucrative contract and an assured future, suggests that she has had all the breaks. Well, Carol has had the breaks — a good many of them bad ones.

For instance, a few months ago Cecil DeMille [Cecil B. DeMille] borrowed her from Pathé, and planned to give her the leading role in Dynamite, his first production for Metro-Goldwyn. Interviewers swarmed about her, photographs by the gross were taken, costume plates were submitted. People grew more cordial and even deferential, which annoyed Carol a little. She didn’t want that kind of friends and attention.

She just wanted her old gang who were all for Carol, whether she was Lombard out of a job, or Lombard elected by the mighty.

And after the first burst of publicity and congratulation had abated somewhat, Carol waited anxiously for the picture to start. She had a good, long wait. The story wasn’t quite right, so there were revisions, conferences, and various delays. After several weeks Pathé decided she couldn’t be spared any longer. They figured that if she made three or four pictures this year, she would be potential star material next year. But it she spent most of this year making one picture at another studio, she would still be just a novice in the eyes of the public. So she was recalled, and cast in High Voltage opposite William Boyd.

There were no tears nor temperamental rages. Carol assumed that men who had been in the picture business a long time knew what they were about. They had money invested in her, and she knew they would manage their investment wisely.

Maybe, when she was alone, she shed a tear or two over the lost chance to he displayed among the lavish fripperies of a DeMille picture, but I doubt it. Hers is a breezy good nature, well fortified against hurts. Experiences that don’t give her a laugh pass quite unnoticed. And when Carol laughs, you need no loud speaker to broadcast it.

There was a time when she did not laugh audibly, but she retained her high spirits through an experience that would have withered a less hardy nature than hers.

Just as she was getting along well in Sennett pictures she was in an automobile collision. For a while it was believed that she would be permanently disfigured. For weeks she lay in the hospital, swathed in bandages, her future in doubt. And when she was discharged, assured that her beauty was not marred, she was told that she would have to spend eight or nine months in seclusion to repair the shock sustained by her nervous system.

Now a year out of motion pictures. I after once being established, is as good as a one-way ticket to oblivion. Casting directors, without looking into the story behind a name, pass it by, saying that So-and-So can’t be much good, because they haven’t been in pictures lately.

Carol spent those months reading plays aloud. Propped up in bed. frequently racked with nervous pain, she had to concentrate on something to take her mind off herself. A complete list of her reading would comprise almost the entire Samuel French catalogue. But it was in the works of Shakespeare that she found the greatest surcease from pain.

Little did she know that those months of reciting lines would prove more valuable than all the picture experience she might have had during that time. Carol read plays, not from any devotion to duty, or any desire to shine among the culture-hungry, but simply because she enjoyed doing it.

I did not know Carol at that time, but I knew many people who did, and I was always impressed by the way they spoke of her. When she was well enough to see a few visitors, no one ever thought of going over merely to cheer her up. An expedition to her house was always in the nature of a party. “Let’s go over to Carol’s and have some laughs,” they would say. As a matter of fact, they didn’t say “Carol” — they said “Jane.” Her real name is Jane Peters, and many of her school friends still call her that. She would have gone on being plain Jane Peters, if studio executives hadn’t objected to such a prosaic name for such a beautiful girl.

“I just want to be happy,” Carol told me one time when I pinned her down long enough to ask her a few questions about herself. “Just now I am crazy about the studio. I can’t stay away from it. If they call me for four in the afternoon, I can hardly stay away at nine in the morning. I like to come over and see everybody, and feel that I am a part of what’s going on.

“I’ve always wanted to act. I went to dramatic school for three years after I finished high school, and they couldn’t hold classes too late for me. Then for a while I was crazy about dancing and swimming and yachting and riding horseback.

“Now I can’t imagine wanting to do anything but make pictures. Later on, maybe, it will be something else. Whatever it is, I’ll do it. I always have a lot of fun.

“When I finished High Voltage I didn’t have a day off, because they used me in making tests. They wanted to make tests of stage actors, and thought it would be easier if they had some one opposite them. I made a test with a chap who had been playing in Candida. One night they handed me a copy of the play, and the next day I did a scene with him. It was all so new to me and such an old story with him, I almost burst out laughing. I thought the test was terrible, but the studio liked it, so it’s all right with me.

“I am going to do a picture with Robert Armstrong next. It is called For Two Cents, and it’s a newspaper story. But I don’t play a sob sister. That’s a distinction for me. I’m one of the few girls who hasn’t played a sob sister this year.”

Carol might be called a siren type, if the word hadn’t become confused with languid ladies, who recline on tiger skins and say “Yes” with alacrity. It’s the fire-alarm sort of siren that suggests her personality. Legend has it that in her school days she was a prim little lady, until she noticed that she was being relegated to the background. Suddenly she bloomed into a flamboyant, hilarious, companionable sort, and she has never suffered from lack of attention since.

Diane Ellis and Sally Eilers were schoolmates of hers, and they are still good friends. They are always hoping to work in the same studio. Carol has never found another studio playmate as congenial as Daphne Pollard, with whom she palled during her Sennett days. Daphne was always ready to join her in any effort to upset the dignity of the leading man.

Carol is scrupulous about remembering engagements and being on time for them. She has never been known to complain of being tired. Her wardrobe is a model of smart sports wear for the young girl. But take it from Carol, she can always be counted on to make the wrong impression. When Joseph P. Kennedy, the big boss of Pathé, came out from New York every one in the studio was anxious to have him see Carol. They were eager to know that his judgment coincided with that of Edmund Goulding, and others, who had proclaimed her the greatest “find” of years. They hoped that he would wander out on a set just as Carol tore into a big dramatic scene, her lovely, sonorous voice making chills run up and down every spine.

But instead she ran into him just as she was leaving the studio. Her hat had seemed tight, so she had given it a shove until it rested on the back of her head. Her blond hair was straggling in the breeze, her coat was half falling off her shoulders, and hands in pockets, she was slouching along whistling.

Even at that the big boss thought her marvelous.

Carol Lombard’s real name, Jane Peters, didn’t suit her lovely face.

Photo by: William E. Thomas (1895–1961)

From the interesting story about Carol Lombard opposite, you might think that her beauty has given her all the breaks to be had, but you need read only a little further to learn that there has been bad luck, too.

Photo by: William E. Thomas (1895–1961)

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, August 1929