Butlers in Movies — “Very Well, Sir” (1929) 🇺🇸

Bless the butlers who work in pictures! If it were not for them, what strange errors in social etiquette the world would see on the screen!

by A. L. Wooldridge

For instance: In one of the studios not long ago, a widely known actress was playing in a formal-dinner scene. Possibly two score were seated at the table. The meat course was being served. The director had looked over the set and given his approval. At one side stood Wilson Benge, as the butler. Lights were ordered and there came the call, “Camera!”

What did this actress do? She grasped the handle of her fork as though it were a dirk and stabbed — absolutely stabbed — her lone piece of meat to the heart, and held it there as though she expected it to wriggle away and run. Then, as she held it pinioned, she cut a long, deep gash in its left flank, repeated the assault and finally began a sawing operation, which in time cut off a fairly small, but badly mangled chunk.

“F’r the sufferin’ love of Mike!” exclaimed the director, in an undertone, when Mr. Benge, the butler, called his attention to the breach. “I wonder how she eats corn on the cob!”

Quietly and as diplomatically as possible the lady was called from the set and given a lesson — probably her first — in how to handle a table tool.

No one sees poor table manners in the movies. This is partly because there usually is present some butler who knows how to “buttle,” and is up on the “thou shalt nots” of aristocratic establishments. Formal dinners on the screen require the presence of technical experts, and that’s where the butlers come in.

“America is a country of right-handed eaters,” says Wilson Benge, who has buttled in more pictures in Hollywood, perhaps, than any other actor. “The diner picks up his knife and fork, cuts off a bite of food, lays down the knife, transfers the fork from the left to the right hand, conveys the food to his mouth, shifts the fork to the left hand again, picks up the knife once more with the right, and so on. This has become an accepted custom. In England diners use both utensils and eat left-handed. Table knives have been in use since early in the sixteenth century, and table forks were introduced in England from Italy during the reign of King James I. Yet, through all these centuries, the world generally has not learned how to use these things the way they should be used. Almost every one commits some error at times.

“But in the movies, errors simply cannot be permitted. If an actor harpoons a piece of bread with his fork when the plate is passed, that part of the film comes out.”

Within the past year a school of eating has been established in Los Angeles by the Marquis Albert de Laurinston, an authority on etiquette. Originally intended for the sole purpose of training maids and butlers to serve Los Angeles households, the school has found a widening field among employers who need a bit of instruction themselves. It undeniably is true that well-trained butlers know correct etiquette far better than the average head of a house. They have studied it. Their employment depends upon a knowledge of it.

“One thing which strikes me as odd in the movies,” says Mr. Benge, “is the presence, almost invariably, of pretty maids. In real life maids may be pretty — but not too pretty. The lady of the house doesn’t let one stay long, if she attracts much notice. About the first time such a maid gets a prolonged smile from the master, she is just the same as on her way to another job.”

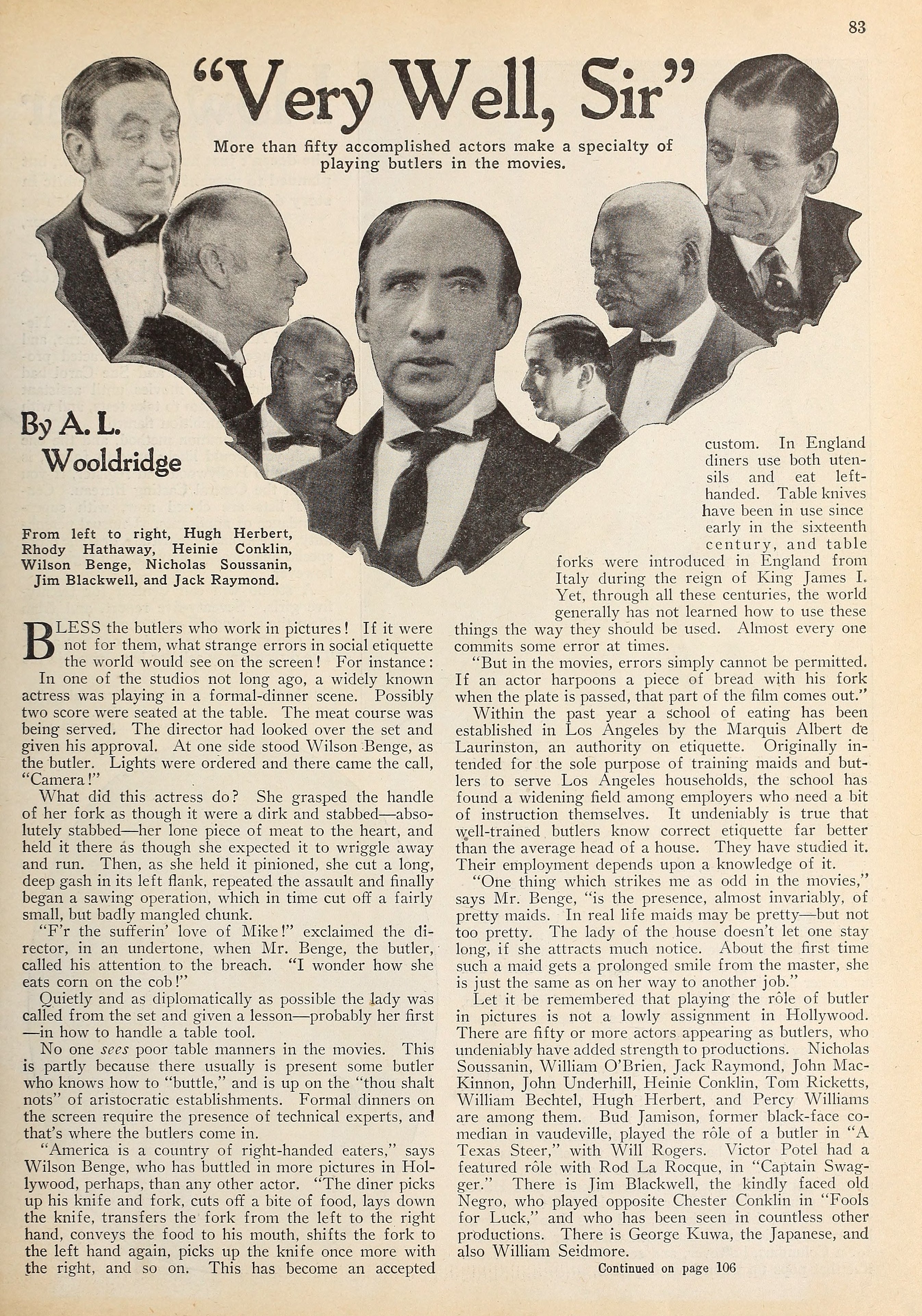

Let it be remembered that playing the role of butler in pictures is not a lowly assignment in Hollywood. There are fifty or more actors appearing as butlers, who undeniably have added strength to productions. Nicholas Soussanin, William O’Brien, Jack Raymond, John MacKinnon, John Underhill, Heinie Conklin, Tom Ricketts, William Bechtel, Hugh Herbert, and Percy Williams are among them. Bud Jamison, former black-face comedian in vaudeville, played the role of a butler in A Texas Steer, with Will Rogers. Victor Potel had a featured role with Rod La Rocque, in Captain Swagger. There is Jim Blackwell, the kindly faced old Negro, who played opposite Chester Conklin in Fools for Luck, and who has been seen in countless other productions. There is George Kuwa, the Japanese, and also William Seidmore.

Charles Green, the dean of butlers, died last year after having played nearly a hundred roles. He was butler at one time to the late Queen Victoria, to the Duke of Cambridge, the Maharajah of Lahore, King Edward VII., Grand Duke Michael of Russia, the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough, and so on. He was the most widely known technical adviser on etiquette in Hollywood.

The screen butlers earn more money than butlers in real life if they know their stuff. Also the maids who know etiquette earn more than the average housemaids. A story is going the rounds in Hollywood about a star, who had a tiff with her maid on the day when she had invited a dozen friends for bridge. When the maid walked out, the actress called up an employment bureau and related her predicament.

“I want some one,” she explained, “who will prepare and serve sandwiches, a bit of punch, some cake and ice cream. If she does well, I may have steady employment for her.”

The maid came — a middle-aged woman with a hooked nose. She carried a bag and a bundle. A frayed cape was about her shoulders, and a bird perched upon her hat.

“Can you serve?” the actress asked.

“Sure, Oi can!” the maid replied.

“There’ll be a dozen or more guests. I’ll tell you when we are ready.”

The guests gathered. The card games were played. Then the hostess called for the refreshments to be served. The new maid did it beautifully — bringing in everything in the proper order and generally qualifying as a jewel. She refilled the glasses, replenished the dishes of salted almonds, placed ash trays for those who had elected to smoke.

“She is a darling,” exulted the hostess, “and I’ll keep her here if I can.”

Came time for the ice cream. The efficient, careful maid heard the hostess’ signal. She knew the first course had been served to the satisfaction of her employer, because the star smiled sweetly over the way the servant had performed her task.

But a moment later the ship was wrecked. The card party — so far as the hostess was concerned — went down in deep water. Because? Well, because the glorious new maid poked her head through the kitchen door and shouted, “Everybody, stack plates!”

If Phyllis Haver reads this story she will never speak to me again, because I don’t think she wanted me to tell. Anyway, Phyllis, it wasn’t your fault.

From left to right, Hugh Herbert, Rhody Hathaway, Heinie Conklin, Wilson Benge, Nicholas Soussanin, Jim Blackwell, and Jack Raymond.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, March 1929