Barbara La Marr — When is Barbara Sincere? (1923) 🇺🇸

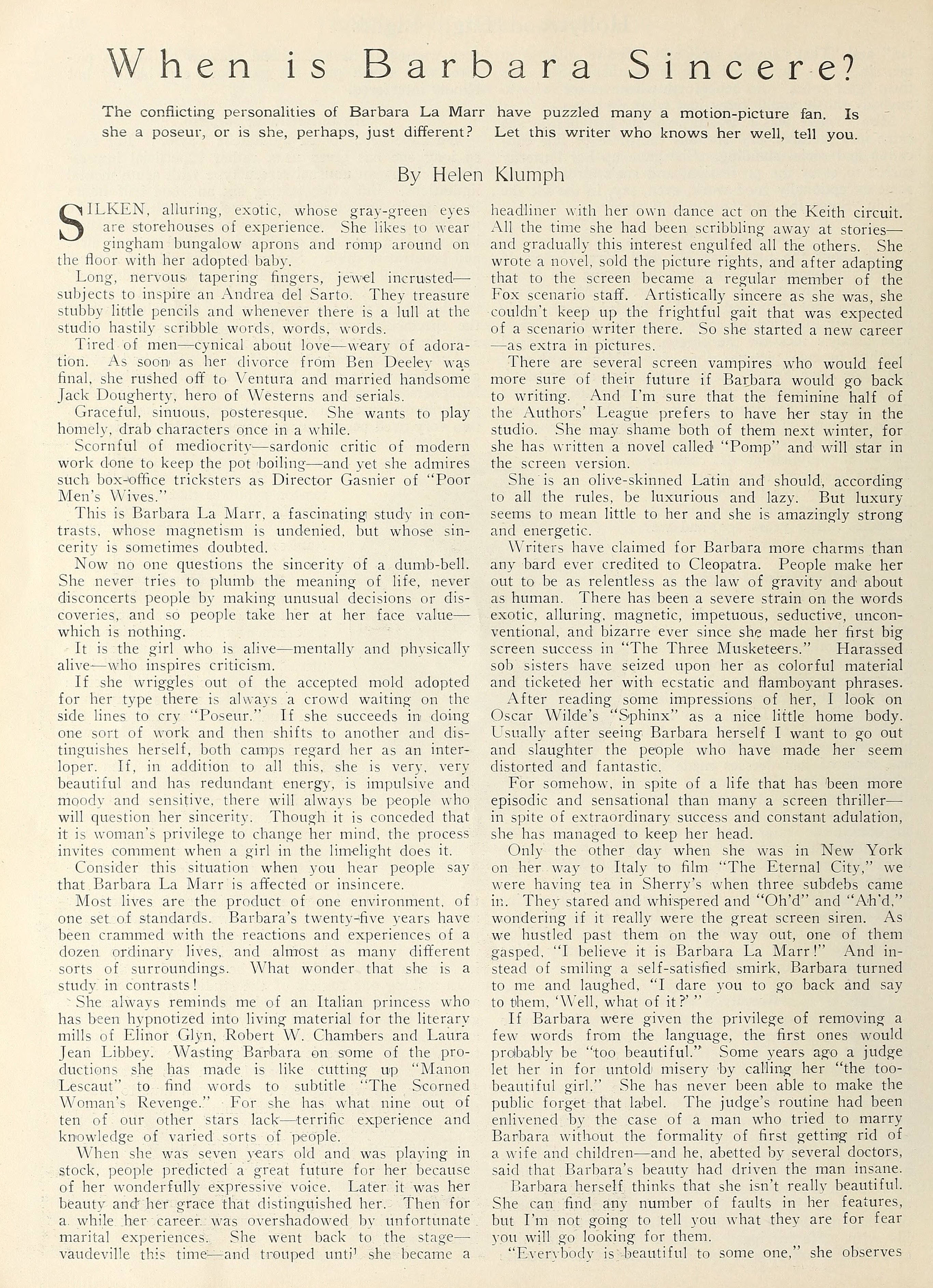

Silken, alluring, exotic, whose gray-green eyes are storehouses of experience. She likes to wear gingham bungalow aprons and romp around on the floor with her adopted baby.

by Helen Klumph

Long, nervous tapering fingers, jewel incrusted — subjects to inspire an Andrea del Sarto. They treasure stubby little pencils and whenever there is a lull at the studio hastily scribble words, words, words.

Tired of men — cynical about love — weary of adoration. As soon as her divorce from Ben Deeley was final, she rushed off to Ventura and married handsome Jack Dougherty, hero of Westerns and serials.

Graceful, sinuous, posteresque. She wants to play homely, drab characters once in a while.

Scornful of mediocrity — sardonic critic of modern work done to keep the pot boiling — and yet she admires such box-office tricksters as Director Gasnier [Louis J. Gasnier] of Poor Men’s Wives.

This is Barbara La Marr, a fascinating study in contrasts, whose magnetism is undenied, but whose sincerity is sometimes doubted.

Now no one questions the sincerity of a dumb-bell. She never tries to plumb the meaning of life, never disconcerts people by making unusual decisions or discoveries, and so people take her at her face value — which is nothing.

It is the girl who is alive — mentally and physically alive — who inspires criticism.

If she wriggles out of the accepted mold adopted for her type there is always a crowd waiting on the side lines to cry “Poseur.” If she succeeds in doing one sort of work and then shifts to another and distinguishes herself, both camps regard her as an interloper. If, in addition to all this, she is very, very beautiful and has redundant energy, is impulsive and moody and sensitive, there will always be people who will question her sincerity. Though it is conceded that it is woman’s privilege to change her mind, the process invites comment when a girl in the limelight does it.

Consider this situation when you hear people say that Barbara La Marr is affected or insincere.

Most lives are the product of one environment, of one set of standards. Barbara’s twenty-five years have been crammed with the reactions and experiences of a dozen ordinary lives, and almost as many different sorts of surroundings. What wonder that she is a study in contrasts!

“She always reminds me of an Italian princess who has been hypnotized into living material for the literary mills of Elinor Glyn, Robert W. Chambers and Laura Jean Libbey. Wasting Barbara on some of the productions she has made is like cutting up Manon Lescaut to find words to subtitle The Scorned Woman’s Revenge. For she has what nine out of ten of our other stars lack — terrific experience and knowledge of varied sorts of people.

When she was seven years old and was playing in stock, people predicted a great future for her because of her wonderfully expressive voice. Later it was her beauty and her grace that distinguished her. Then for a while her career was overshadowed by unfortunate marital experiences. She went back to the stage — vaudeville this time—and trouped until she became a headliner with her own dance act on the Keith circuit. All the time she had been scribbling away at stories — and gradually this interest engulfed all the others. She wrote a novel, sold the picture rights, and after adapting that to the screen became a regular member of the Fox scenario staff. Artistically sincere as she was, she couldn’t keep up the frightful gait that was expected of a scenario writer there. So she started a new career — as extra in pictures.

There are several screen vampires who would feel more sure of their future if Barbara would go back to writing. And I’m sure that the feminine half of the Authors’ League prefers to have her stay in the studio. She may shame both of them next winter, for she has written a novel called “Pomp” and will star in the screen version.

She is an olive-skinned Latin and should, according to all the rules, be luxurious and lazy. But luxury seems to mean little to her and she is amazingly strong and energetic.

Writers have claimed for Barbara more charms than any bard ever credited to Cleopatra. People make her out to be as relentless as the law of gravity and about as human. There has been a severe strain on the words exotic, alluring, magnetic, impetuous, seductive, unconventional, and bizarre ever since she made her first big screen success in The Three Musketeers. Harassed sob sisters have seized upon her as colorful material and ticketed her with ecstatic and flamboyant phrases.

After reading some impressions of her, I look on Oscar Wilde’s “Sphinx” as a nice little home body. Usually after seeing Barbara herself I want to go out and slaughter the people who have made her seem distorted and fantastic.

For somehow, in spite of a life that has been more episodic and sensational than many a screen thriller — in spite of extraordinary success and constant adulation, she has managed to keep her head.

Only the other day when she was in New York on her way to Italy to film The Eternal City, we were having tea in Sherry’s when three subdebs came in. They stared and whispered and “Oh’d” and “Ah’d,” wondering if it really were the great screen siren. As we hustled past them on the way out, one of them gasped, “I believe it is Barbara La Marr!” And instead of smiling a self-satisfied smirk, Barbara turned to me and laughed, “I dare you to go back and say to them, ‘Well, what of it?’”

If Barbara were given the privilege of removing a few words from the language, the first ones would probably be “too beautiful.” Some years ago a judge let her in for untold misery by calling her “the too beautiful girl.” She has never been able to make the public forget that label. The judge’s routine had been enlivened by the case of a man who tried to marry Barbara without the formality of first getting rid of a wife and children — and he, abetted by several doctors, said that Barbara’s beauty had driven the man insane.

Barbara herself thinks that she isn’t really beautiful. She can find any number of faults in her features, but I’m not going to tell you what they are for fear you will go looking for them.

“Everybody is beautiful to some one,” she observes when people insist that they think she is a real beauty.

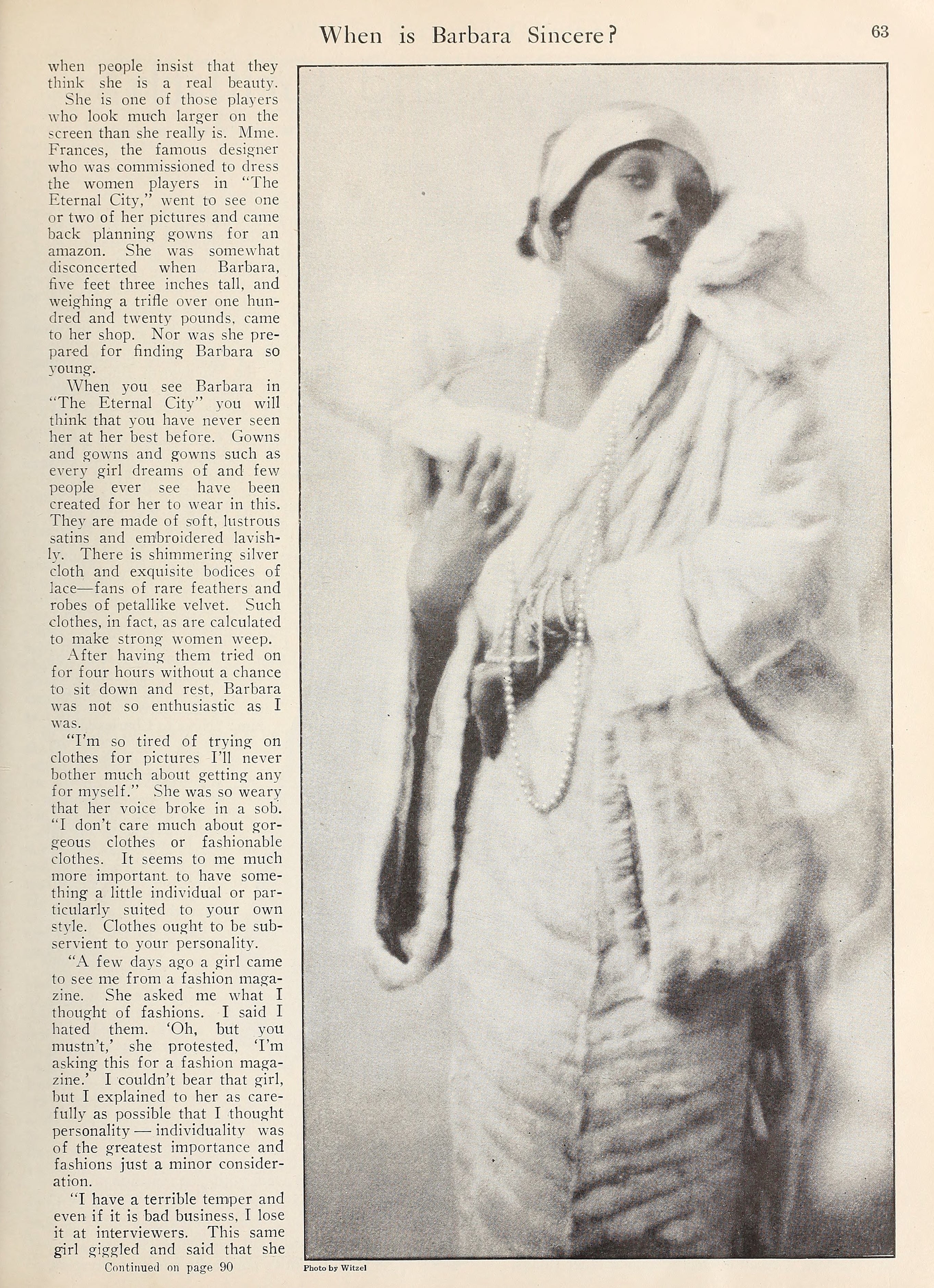

She is one of those players who look much larger on the screen than she really is Mme. Frances, the famous designer who was commissioned to dress the women players in The Eternal City, went to see one or two of her pictures and came back planning gowns for an amazon. She was somewhat disconcerted when Barbara, five feet three inches tall, and weighing a trifle over one hundred and twenty pounds, came to her shop. Nor was she prepared for finding Barbara so young.

When you see Barbara in The Eternal City you will think that you have never seen her at her best before. Gowns and gowns and gowns such as every girl dreams of and few people ever see have been created for her to wear in this. They are made of soft, lustrous satins and embroidered lavishly. There is shimmering silver cloth and exquisite bodices of lace — fans of rare feathers and robes of petallike velvet. Such clothes, in fact, as are calculated to make strong women weep.

After having them tried on for four hours without a chance to sit down and rest, Barbara was not so enthusiastic as I was.

“I’m so tired of trying on clothes for pictures I’ll never bother much about getting any for myself.” She was so weary that her voice broke in a sob. “I don’t care much about gorgeous clothes or fashionable clothes. It seems to me much more important to have something a little individual or particularly suited to your own style. Clothes ought to be subservient to your personality.

“A few days ago a girl came to see me from a fashion magazine. She asked me what I thought of fashions. I said I hated them. ‘Oh, but you mustn’t,’ she protested, ‘I’m asking this for a fashion magazine.’ I couldn’t bear that girl, but I explained to her as carefully as possible that I thought personality — individuality was of the greatest importance and fashions just a minor consideration.

“I have a terrible temper and even if it is bad business, I lose it at interviewers. This same girl giggled and said that she thought my adopting a baby was awfully funny. Funny! Nobody can say to me that they think my baby is funny.”

Barbara has a highly original way of saving herself the bother of shopping for clothes for herself. She advertised for a secretary whose height and weight were the same as hers, who wore the same size gloves and shoes. By a happy coincidence the girl’s taste in hats coincides with Barbara’s. So now she does the shopping for two.

Barbara is rather cool and analytical and not given to bubbling with enthusiasm. All of which makes her tremendous admiration for Blanche Sweet more notable and lends importance to the fact that she thinks Fred Niblo has made a great picture of Captain Applejack. She wants to play Monna Vanna and Manon Lescaut when she comes back from Europe — she wants to idle in the garden of her beautiful new Los Angeles home on Whitley Heights with the baby, whom she adores. She wants time to write the many stories she has planned. She wants, too, the stimulus of New York’s high artistic standards.

Child of a thousand and one influences, she is pulled this way and that by conflicting desires. Are they genuine? Is she sincere?

I believe she is.

Photo by: Albert Witzel (1879–1929)

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, September 1923