André Beranger — He Takes His Comedy Straight (1927) 🇺🇸

The parents of Andre Beranger must have taken a week off to christen him — Georges Augustus Alexandre Roger de l’Ile de Beranger. Any one who can pronounce all that knows how to speak French. And must be sober. Mr. Beranger is French, of course — at least in parentage.

by Alma Talley

His parents arrived in Australia just about the time of his birth, and he grew up there. He used to be George Beranger back in the old D. W. Griffith days of Intolerance and The Birth of a Nation, but now he is Andre Beranger, with or without the “de.” Andre is shortened from Alexandre — it must be convenient to pick oneself out a new name every now and then just by reaching into a grab bag supplied at one’s christening.

You remember Mr. Beranger, of course? As George he was an emotional actor, who struggled along for years with little recognition. As Andre he is the marvelous farceur who played in Are Parents People?, So This is Paris and, recently, in The Popular Sin.

He was helping to make sin popular when I saw him, at the Famous Players Long Island studio. And he greeted me with twenty-one photos of himself under his arm. We sat down midst all the lumber and pipes and electric wires that one tries not to fall over in a motion-picture studio.

“This,” he said, taking out the first picture, “is I as Malvolio. When I was sixteen I played Shakespearean roles on the stage in Australia. You see, I naturally have a tenor voice,” he explained, “but when I was sixteen my voice was changing and it was bass — so I played Shakespeare juveniles.”

With this explanation he carefully wrote on the back of the photo, “Andre Beranger as Malvolio in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.”

He was about to do as well by the portrait of himself as Romeo, but I assured him earnestly, after an alarmed glance at that pile of twenty-one pictures, that I would try to remember what play Romeo appeared in, and who wrote it.

He only wanted to make things easier for me, he explained, by writing down what plays all the photos came from.

“But,” I pointed out, “we can’t use all those pictures. Why don’t you let me pick out three or four, and you keep the rest?”

Mr. Beranger is generous. He wanted Picture-Play to have them all — those we didn’t use now might come in handy later. And we’d want to know, wouldn’t we, what all those characterizations were? So he went on, with pencil in hand, and I settled down to one of those quaint afternoons among the photograph albums. Mr. Beranger had the familiar explanatory manner that goes with such a session — “This is the time when Margaret and Dick and I got stuck in the mud; it was just a scream” — that sort of thing, you know.

Well, in the same way, I learned all about the plays Andre, or George, had played in — and the films. The films dated back to 1912, and the plays came even earlier. All the time, he was beaming at the interviewer, with a smile that turns up into a right angle at each corner. His black hair is thick and curly; his big brown eyes, were, at the moment, intent on his job of labeling photos. He wore a black dressing gown edged with red, on top of his checked trousers — to go with a morning coat— and pink shirt. He explained that this camera man preferred pink shirts to blue ones, for photographic purposes. He had asked him, and that’s what the camera man had said — pink.

“This isn’t going to be much of an interview,” I complained finally, growing restless when there were still ten pictures to go. “Just a list of the pictures you’ve played in since 1912, and the plays before that. I came out to interview a farceur, not a photograph album.”

“That’s right!” He lit a cigarette. “You know, the other day, a woman passed me on the street and she said to her friend, ‘Oh, there goes that actor with all the birdlike gestures.’ You can’t imagine how pleased I was at being recognized.”

In fact, you might describe Georges Augustus and-all-the-rest-of-it Beranger as being very, very much pleased these prosperous days. Pleased at being recognized on the street, pleased at being interviewed, and nothing short of delighted at his recent onset of prominence in the films.

“Look at this!” he said. The pictures were now exhausted, so he produced a newspaper clipping referring anonymously to “an actor” who, he assured me, was himself. The clipping was from an interview with a certain well-known leading lady.

“This actor,” the girl was quoted as saying, “was absolutely the dumbest man I’ve ever met. In the picture in which we played together, he was cast as a comedian and didn’t know it. He performed his role so dramatically that it turned out even funnier than the director expected. Once I protested to the director. ‘You just see,’ was his answer, ‘when the picture’s done, he’ll be the best in the cast.’ And he was — just because he was so dumb!”

I looked up in amazement at Mr. Beranger’s eagerness to show me such a clipping about himself.

“The funny part of it is,” he explained, “the joke is on the little leading lady. She’s the dumb one. She doesn’t know the least thing about playing comedy. It was just the fact that I wasn’t being consciously funny that made the role a success. You know yourself that nothing is less humorous than a man who gets up and says, ‘Now I’m being funny.’ The very moment a comedian knows he is funny — and shows it — he ceases to be amusing.”

There is no denying that statement. And Mr. Beranger lives up to it — he is never consciously funny.

He lit another cigarette and reached into his pocket again. I waited anxiously to see what would come out — we had had photographs, a clipping, there was just a chance that this time it would be a Belgian hare or a grand piano.

“I was wondering what I should say to you,” he remarked, drawing little slips of paper out of his pocket, “so I jotted some things down.”

Sure enough, there were half a dozen pink slips of paper, all covered with writing — the things that Andre Beranger had planned to tell the interviewer.

“Hard knocks and vicissitudes in this life teach one to be neither optimistic nor pessimistic, but philosophical,” the first one read. I didn’t read any further. I looked at him again to make sure that I was really talking to Andre Beranger, farceur, and not — say — Doctor Frank Crane.

“I’ve certainly had my share of hard knocks,” he continued. “As I said, I played all sorts of Shakespearean roles when I was sixteen. Then in 1912, I left Australia headed for Broadway. In California, on my way to New York, I met Mr. Griffith and he engaged me to work with him. I was with him for seven or eight years, doing all sorts of things — acting, directing, prop boy, everything, waiting for my big chance. Sometimes he’d say to me, ‘George, if any one doesn’t behave around here, fire him!’ But of course, I wouldn’t fire anybody. The other day, I saw Mr. Griffith again, here at the studio, and he said, ‘Well, I always knew that some day you’d get over big. Some players make successes overnight and others struggle for it for years. I always felt that yours would be a long pull, but that some day you would get over.’”

Mr. Beranger has at last “got over.” He has found his niche. After years and years of emoting, he turned out to be a comedian. It was the advent of the recently popular “polite comedy” type of picture which gave him a conspicuous place on the screen. Almost, one might say, against his will.

It started with Are Parents People? — Andre’s success, that is.

Mr. Lubitsch [Ernst Lubitsch] probably started the vogue for that type of picture. Anyway, Beranger was offered a role in Are Parents People?, Mal St. Clair [Malcolm St. Clair] told him to look over the script, and Beranger passed it back in disgust. He announced that there weren’t any picture possibilities in that. He wasn’t going to play such a role — at that time, you see, George Beranger was still an emotional actor, a little insulted, I take it, that he had been offered light comedy!

So his refusal was flat, and all settled apparently — and then one day Andre got a call from Famous Players to report to Mr. St. Clair.

“What are you here for?” asked the director, in surprise, when he turned up. The situation was equally puzzling to them both, until Mr. St. Clair got in touch with the casting department. It seems that some one in that office had been looking through picture files and, seeing Andre’s photograph, had decided he was just the man for the role which, it happened, he had already refused.

The upshot of it was, Andre took the part. Despite his initial contempt for the script, the picture proved to be delightful; he is still a little bewildered at its success. And, to his even greater surprise, he had found his niche — as a comedian. His ability to play unconscious comedy has made him sought after ever since, for those delightful, sophisticated comedies popularized by Lubitsch, St. Clair, and Monta Bell.

Now he is working constantly, making money — a success after all these years. He told me of two offers he had had from large film companies for contracts; but he is in the enviable position of being able to free-lance successfully, always assured of work.

“The thing that worries me most, financially,” he said, “is my wardrobe. You can’t wear the same suit in two successive pictures. You can wear a suit, say, in this picture, but not again until about three pictures from now. So you have to have many of them, and they must be expensively tailored or they won’t look well in this type of film. And around the studios they get ruined.

“For instance, one suit which cost me one hundred and seventy-five dollars was ruined in one picture. I had to take the coat off, drape it across the back of a chair, and then the chair was slung across the room.

“‘Hey,’ I said, when I found that out, ‘can’t you substitute some old coat for that in the throwing scene?’ ‘No,’ the director said, ‘we haven’t got any stray coats around here for substitutes.’ By the time that scene was rehearsed over and over the coat was ruined.

“Another time, I was wearing a dress suit, and a girl was supposed to hang on to my coat tails. You can imagine what a few rehearsals did to that one!”

At this point in our discussion, Clive Brook strolled over — he is also appearing in The Popular Sin.

“Are those all the pictures he gave you?” said Clive, flipping through those twenty-one photos. “He usually treats interviewers better than that.”

Greta Nissen, also in the picture, was sitting near by reading a book, in Norwegian.

“Look,” said Mr. Beranger, being, at last, a farceur who meant to be funny, “all the words are spelled wrong.”

But Mr. Georges Augustus Alexandre Roger de l’Ile de Beranger seldom intends to be funny. He has saved all the costumes that he ever wore in his characterizations and, so they say at the studio, he likes best to put on the Hamlet one. It may or may not be a source of chagrin to him that he has made his success as a farceur. At least he can be consoled by the offers that now pour in on all sides for his services.

All good comedians have a quality of pathos in their make-up perhaps the discerning may find this quality in Andre Beranger — the actor who plays his comedy straight.

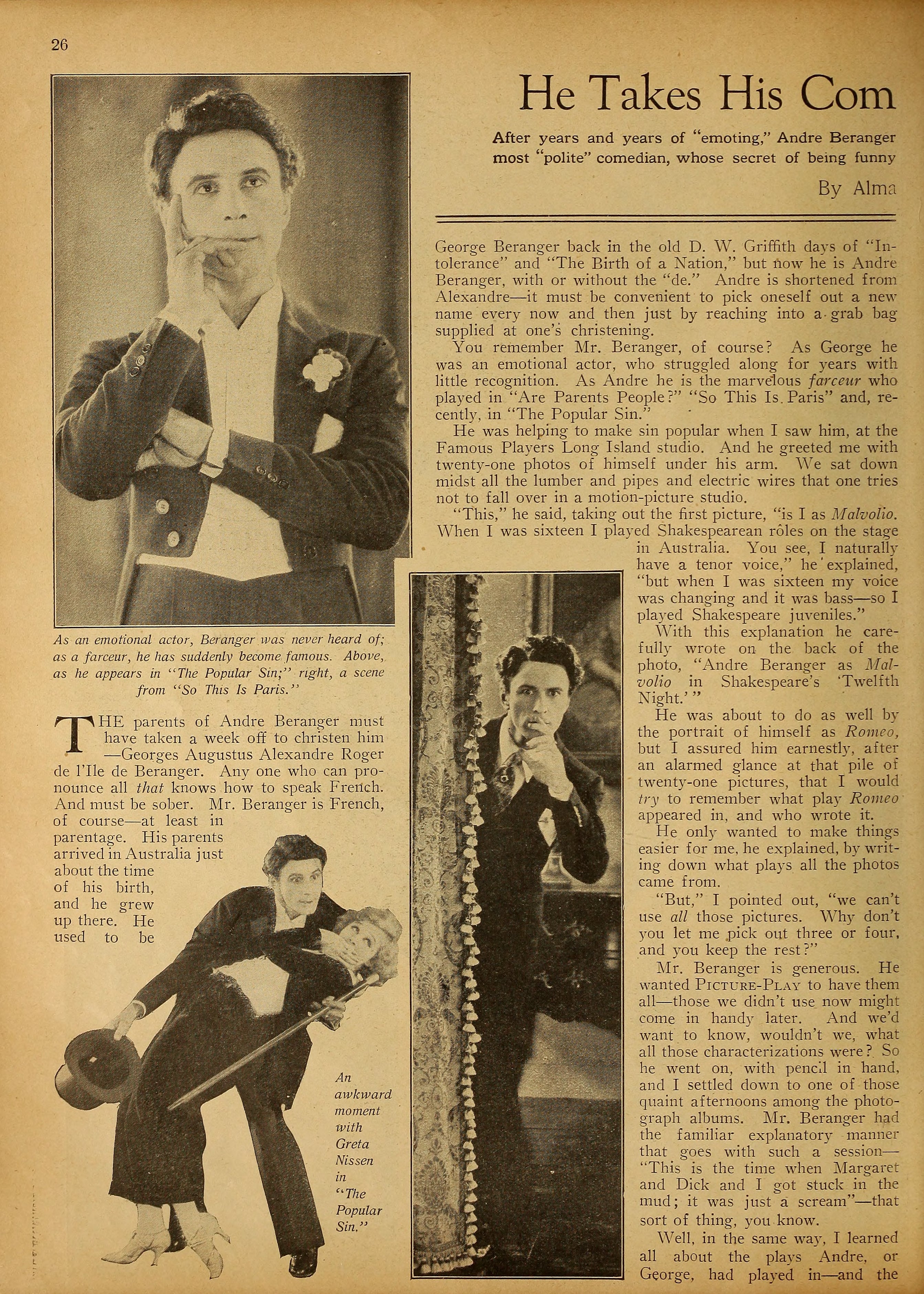

As an emotional actor, Beranger was never heard of; as a farceur, he has suddenly become famous. Above, as he appears in The Popular Sin, right, a scene from So This is Paris.

An awkward moment with Greta Nissen in The Popular Sin.

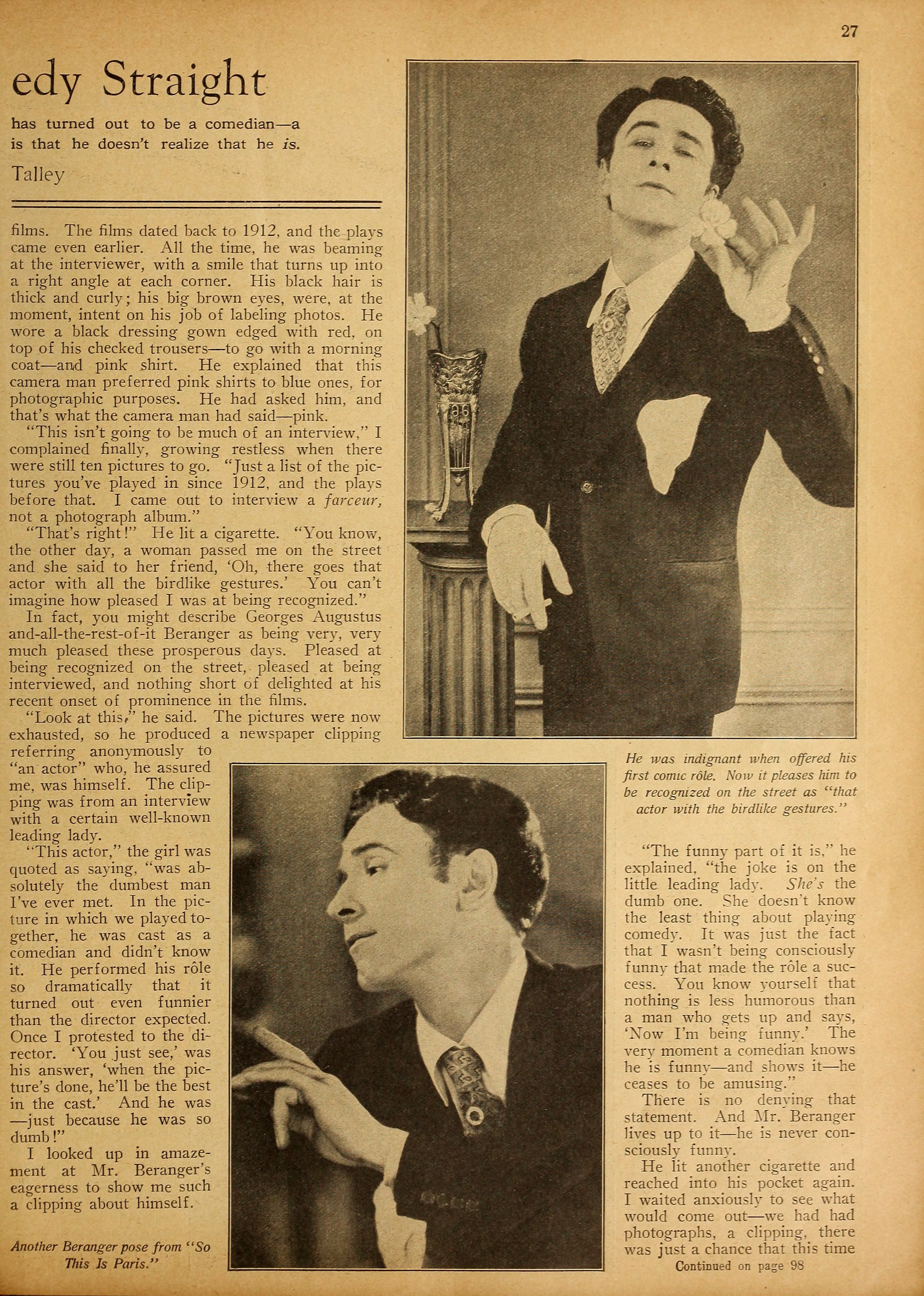

Another Beranger pose from So This is Paris.

He was indignant when offered his first comic role. Now it pleases him to be recognized on the street as “that actor with the birdlike gestures.”

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, January 1927