Alec Francis — Gray Hairs and Stardom (1927) 🇺🇸

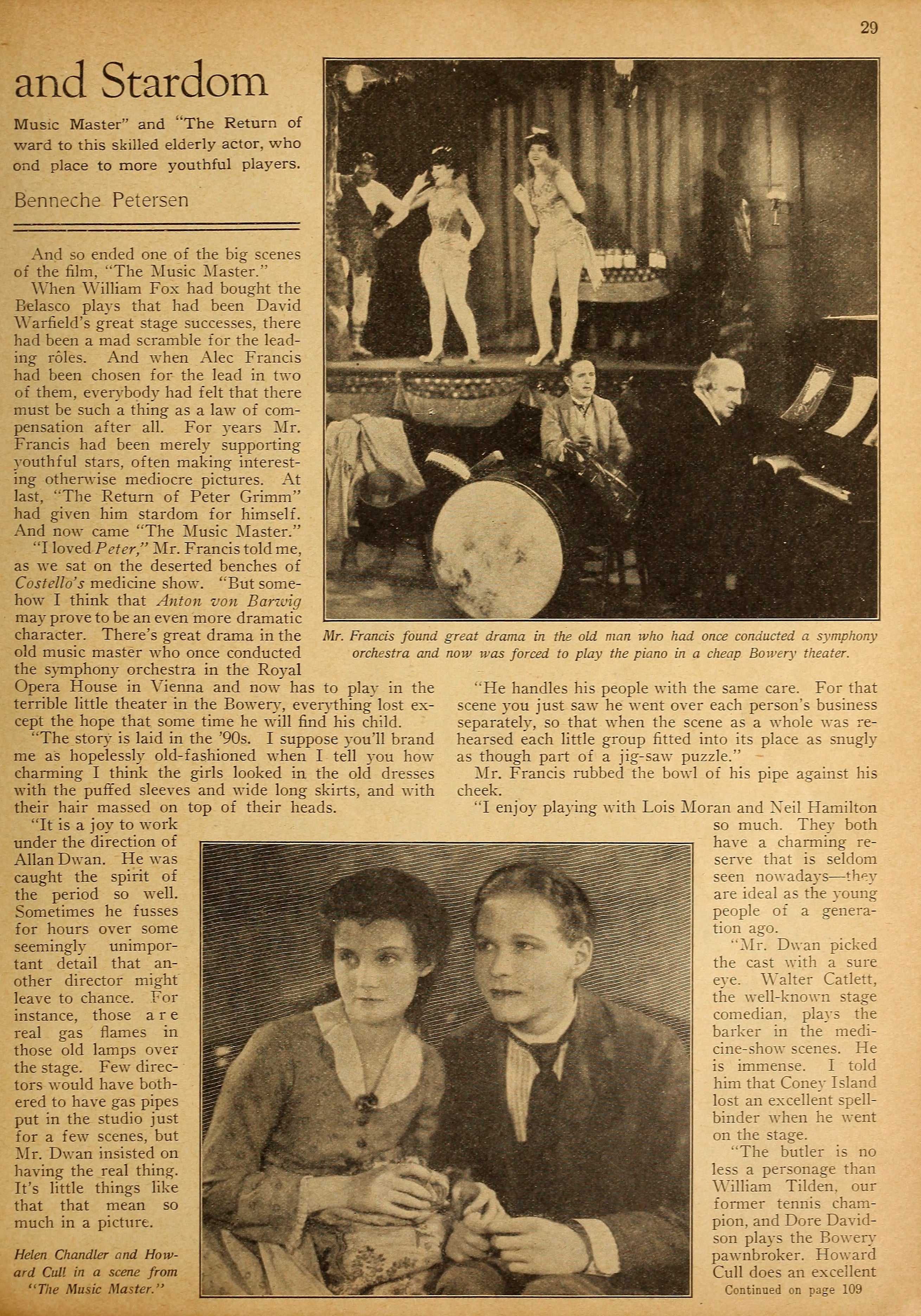

An old man in a shabby black cape and a broad-brimmed hat shambled down the aisle of a shoddy little theater. Gaudy lithographs advertised “Costello’s Medicine Show.” Standing on the garish stage were two voluptuous burlesque queens, curved in keeping with the fashionable hourglass silhouette of the gay ‘90s. They looked like the bouncing wenches who used to grace the grocery-store calendars. Vivid-pink tights emphasized the full curves of their hips and wasplike waists. The hair of each was a mass of curls and puffs and artificial flowers.

by Elizabeth Benneche Petersen

”My Gawd, I can’t breathe,” came from the smiling lips of one, as she lumbered into a labored dance step.

”Can you beat it?” agreed the other. “Imagine any one goin’ through life in a strait-jacket like this. Just imagine!”

The old man sat down at the piano. The light of the gas lamps hanging over the stage fell on his white head like a benediction. For a moment his long fingers caressed the stained keys wistfully. A fragment of Chopin was startled into life. Then the expressive fingers stopped. When they moved again, the lively strains of “Tara-ra boomdeay” filled the little theater.

As though the music was a signal, a crowd of people swarmed down the single aisle, fighting for possession of the wooden benches. There were Jewish patriarchs with long white beards, old women in shawls, and girls in wide skirts, short jackets, and enormous leg-of-mutton sleeves. There were ragged urchins and swaying men. They were the same types that abound in New York’s Bowery to-day — starved bodies and bleak faces. Only the clothes were different.

A man in a black-and-white-check suit, whose hair was as smooth and shiny as patent leather, leaped to the stage. Holding aloft a bottle of the Costello magic cure, he launched into a verbal eulogy. His every gesture was superb, even if he merely flicked the ash off his cigar.

Two girls who had not found seats in the crowded hall stood in the rear and watched the speaker with the bored expressions of those who had heard him many times. Their eyes swept the audience appraisingly as they chewed their gum nonchalantly and with finesse. One of them toyed elegantly with a feather boa.

The old man at the piano played on. Unwillingly his fingers moved swiftly over the keys. Suddenly his brooding eyes met the wide gaze of a child. A new look swept over his face, a smile softened his mouth. The strident strains of the popular song faltered into silence. There came instead the crooning lilt of a lullaby. The old man’s head nodded — gently, caressingly.

The girls in the pink tights missed a step, the audience jeered derisively. A tired old man looked about in the dazed manner of a dreamer suddenly awakened. Then he remembered. Once more his fingers leaped over the keys. “Ta-ra-ra boomdeay! Ta-ra-ra boomdeay!” The girls sashayed back and forth — one, two, three, skip; one, two, three, skip.

And so ended one of the big scenes of the film, The Music Master.

When William Fox had bought the Belasco plays that had been David Warfield’s great stage successes, there had been a mad scramble for the leading roles. And when Alec Francis had been chosen for the lead in two of them, everybody had felt that there must be such a thing as a law of compensation after all. For years Mr. Francis had been merely supporting youthful stars, often making interesting otherwise mediocre pictures. At last, The Return of Peter Grimm had given him stardom for himself. And now came The Music Master.

”I loved Peter,” Mr. Francis told me, as we sat on the deserted benches of Costello’s medicine show. “But somehow I think that Anton von Banuig may prove to be an even more dramatic character. There’s great drama in old music master who once conducted the symphony orchestra in the Royal Opera House in Vienna and now has to play in the terrible little theater in the Bowery, even-thing lost except the hope that some time he will find his child.

”The story is laid in the ‘90s. I suppose you’ll brand me as hopelessly old-fashioned when I tell you how charming I think the girls looked in the old dresses with the puffed sleeves and wide long skirts, and with their hair massed on top of their heads.

”It is a joy to work under the direction of Allan Dwan. He was caught the spirit of the period so well. Sometimes he fusses for hours over some seemingly unimportant detail that another director might leave to chance. For instance, those are real gas flames in those old lamps over the stage. Few directors would have bothered to have gas pipes put in the studio just for a few scenes, but Mr. Dwan insisted on having the real thing. It’s little things like that that mean so much in a picture.

”He handles his people with the same care. For that scene you just saw he went over each person’s business separately, so that when the scene as a whole was rehearsed each little group fitted into its place as snugly as though part of a jig-saw puzzle.”

Mr. Francis rubbed the bowl of his pipe against his cheek.

”I enjoy playing with Lois Moran and Neil Hamilton so much. They both have a charming reserve that is seldom seen nowadays — they are ideal as the young people of a generation ago.

’”Mr. Dwan picked the cast with a sure eye. Walter Catlett, the well-known stage comedian, plays the barker in the medicine-show scenes. He is immense. I told him that Coney Island lost an excellent spellbinder when he went on the stage.

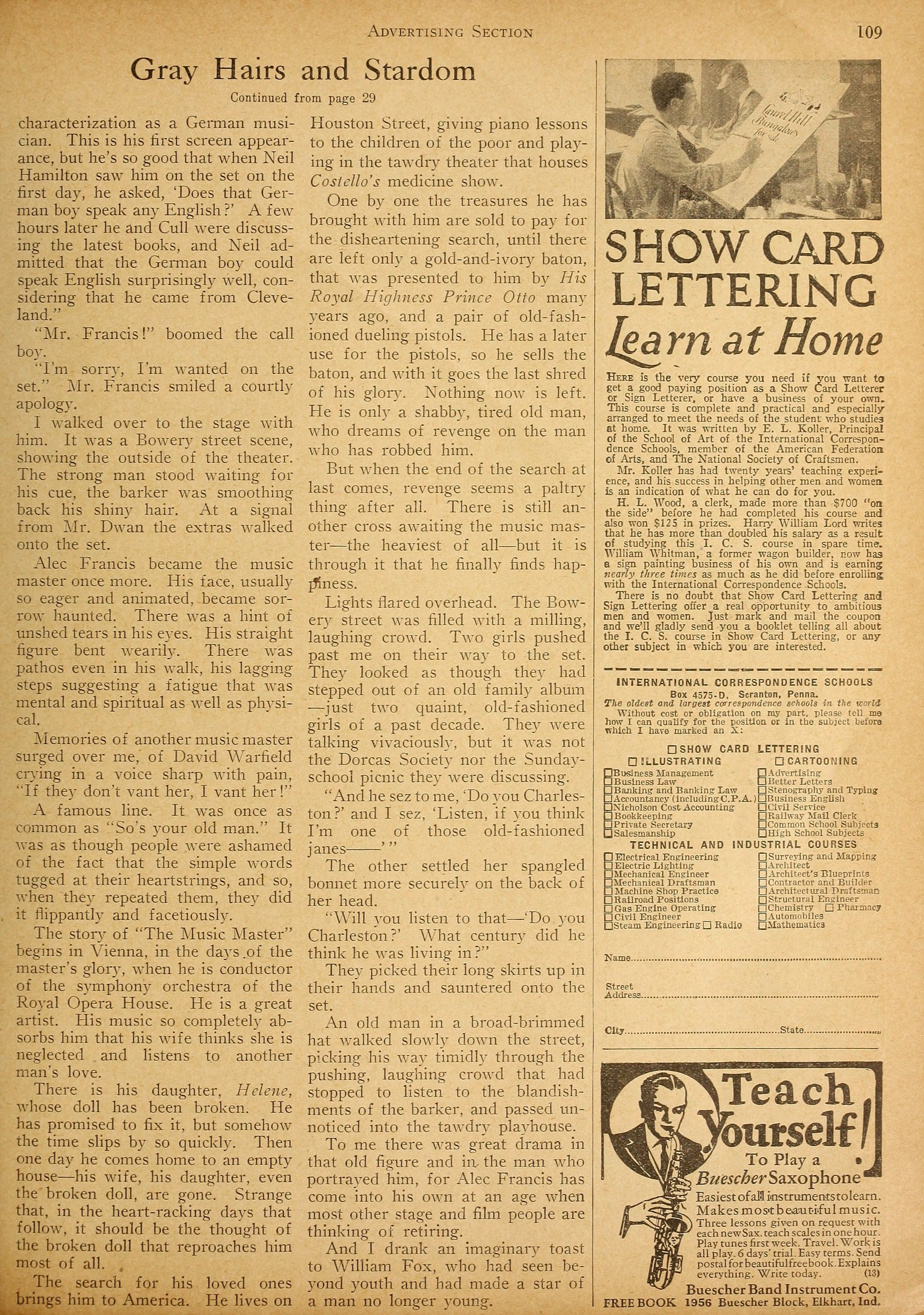

”The butler is no less a personage than William Tilden, our former tennis champion, and Dore Davidson plays the Bowery pawnbroker. Howard Cull does an excellent characterization as a German musician. This is his first screen appearance, but he’s so good that when Neil Hamilton saw him on the set on the first day, he asked, ‘Does that German boy speak any English?’ A few hours later he and Cull were discussing the latest books, and Neil admitted that the German boy could speak English surprisingly well, considering that he came from Cleveland.”

”Mr. Francis!” boomed the call boy.

”I’m sorry, I’m wanted on the set.” Mr. Francis smiled a courtly apology.

I walked over to the stage with him. It was a Bowery street scene, showing the outside of the theater. The strong man stood waiting for his cue, the barker was smoothing back his shiny hair. At a signal from Mr. Dwan the extras walked onto the set.

Alec Francis became the music master once more. His face, usually so eager and animated, became sorrow haunted. There was a hint of unshed tears in his eyes. His straight figure bent wearily. There was pathos even in his walk, his lagging steps suggesting a fatigue that was mental and spiritual as well as physical.

Memories of another music master surged over me, of David Warfield crying in a voice sharp with pain, “If they don’t vant her, I vant her!”

A famous line. It was once as common as “So’s your old man.” It was as though people were ashamed of the fact that the simple words tugged at their heartstrings, and so, when they repeated them, they did it flippantly and facetiously.

The story of The Music Master begins in Vienna, in the days. of the master’s glory, when he is conductor of the symphony orchestra of the Royal Opera House. He is a great artist. His music so completely absorbs him that his wife thinks she is neglected and listens to another man’s love.

There is his daughter, Helene, whose doll has been broken. He has promised to fix it, but somehow the time slips by so quickly. Then one day he comes home to an empty house — his wife, his daughter, even the broken doll, are gone. Strange that, in the heart-racking days that follow, it should be the thought of the broken doll that reproaches him most of all.

The search for his loved ones brings him to America. He lives on Houston Street, giving piano lessons to the children of the poor and playing in the tawdry theater that houses Costello’s medicine show.

One by one the treasures he has brought with him are sold to pay for the disheartening search, until there are left only a gold-and-ivory baton, that was presented to him by His Royal Highness Prince Otto many years ago, and a pair of old-fashioned dueling pistols. He has a later use for the pistols, so he sells the baton, and with it goes the last shred of his glory. Nothing now is left. He is only a shabby, tired old man, who dreams of revenge on the man who has robbed him.

But when the end of the search at last comes, revenge seems a paltry thing after all. There is still another cross awaiting the music master — the heaviest of all — but it is through it that he finally finds happiness.

Lights flared overhead. The Bowery street was filled with a milling, laughing crowd. Two girls pushed past me on their way to the set. They looked as though they had stepped out of an old family album — just two quaint, old-fashioned girls of a past decade. They were talking vivaciously, but it was not the Dorcas Society nor the Sunday-school picnic they were discussing.

”And he sez to me, ‘Do you Charleston?’ and I sez, ‘Listen, if you think I’m one of those old-fashioned janes —’”

The other settled her spangled bonnet more securely on the back of her head.

”Will you listen to that — ‘Do you Charleston?’ What century did he think he was living in?”

They picked their long skirts up in their hands and sauntered onto the set.

An old man in a broad-brimmed hat walked slowly down the street, picking his way timidly through the pushing, laughing crowd that had stopped to listen to the blandishments of the barker, and passed unnoticed into the tawdry playhouse.

To me there was great drama in that old figure and in the man who portrayed him, for Alec Francis has come into his own at an age when most other stage and film people are thinking of retiring.

And I drank an imaginary toast to William Fox, who had seen beyond youth and had made a star of a man no longer young.

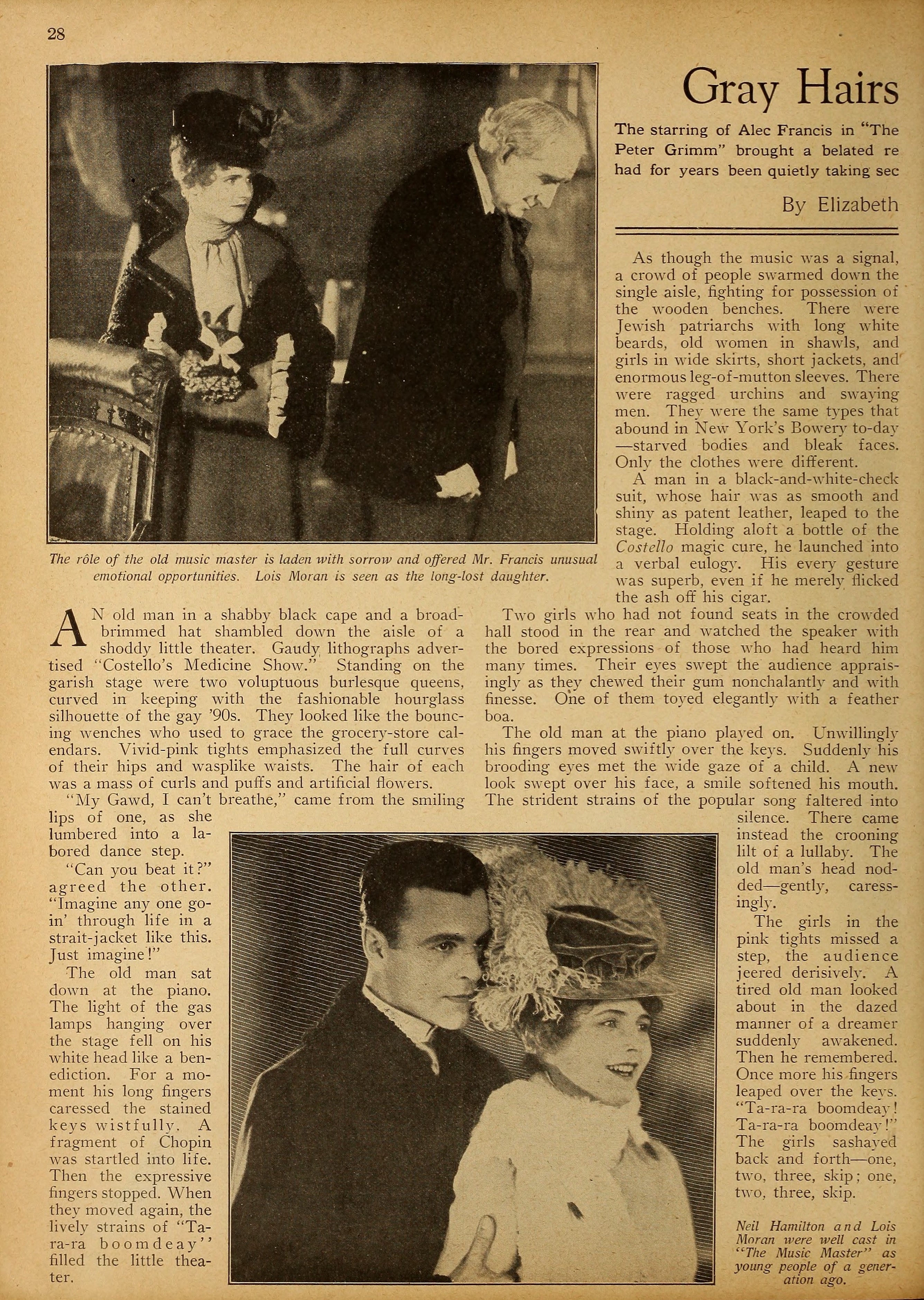

The role of the old music master is laden with sorrow and offered Mr. Francis unusual emotional opportunities. Lois Moran is seen as the long-lost daughter.

Neil Hamilton and Lois Moran were well cast in The Music Master as young people of a generation ago.

Mr. Francis found great drama in the old man who had once conducted a symphony orchestra and now was forced to play the piano in a cheap Bowery theater.

Helen Chandler and Howard Cull in a scene from The Music Master.

Collection: Picture Play Magazine, April 1927