Leslie Caron — I was a Convent Girl (1953) 🇺🇸

Tenaciously, eight-year-old Leslie Caron held on to the side of the eight wheel truck which lumbered through a busy, cobble-stone street of Paris. Her feet, wearing a pair of shiny new roller skates, sometimes barely touched the ground, but her eyes were gleaming with excitement. Suddenly the truck made a sharp left turn into a narrow alley. Leslie lost her grip and sailed straight into a sidewalk vegetable stand, spilling fruit and vegetables all over the street.

by Peer J. Oppenheimer

Fifteen minutes later, clothes torn and smeared liberally with the juices and saps of tomatoes, bananas, squash, and a few other “legumes,” Leslie meekly confronted her mother. “I am very sorry, maman, I… I…”

Maman was “very sorry” too. More than that! “Mon Dieu, mon Dieu, we cannot go on like this. We’ll have to make a lady out of you somehow…”

Two weeks later, Leslie reported to the convent school in La Rue Des Dames.

The truck incident was the final link in a chain of happenings that made Mme. Caron decide that an upbringing in a convent school would be the best, the only solution for her tomboyish daughter.

While other girls her age had played house, hopscotch, or jumped rope, Leslie chased cars, swung from trees or went on the warpath — in the French version of an American Sioux — terrorizing the neighborhood in her own little ways.

In America, this sort of tomboyishness may be considered “cute” and within limits, condoned by the public at large. Not in France, however, where proper behavior for young ladies is prescribed by strict etiquette — and this doesn’t include war games and the like.

From the time she was eight until she was graduated, Leslie attended a variety of convents and parochial schools — first L’Ecole in La Rue des Dames, till she turned ten. During the German invasion of France, her parents sent her to the St. Jean de Luz convent, near the famous resort town of Biarritz, on the Bay of Biscay. Then back to Paris and the Convent de L’Assumption and finally the parochial school in the Rue de Lubeck, near L’Eville.

Different in names and location only, the life in these convents and parochial schools was very much the same. It was based on strict discipline, insistence on good manners and rigid concentration on learning.

Punishment even for minor misdemeanors was swift. Offenses such as forgetting to curtsy to a Sister, not getting up quickly enough when the teacher came into the room, or, as happened more than once to Leslie, letting vanity get the upper hand, quickly placed one in the “punishment seat” in front of the class, or eliminated the offender from the two daily recreational exercises.

Leslie’s own love for pretty clothes somewhat contradicted her tomboyishness.

Particularly her weakness for silly little hats, which she herself made. This, more than anything else, got young Miss Caron into the most uncomfortable situations.

At the Convent de L’Assumption, for instance, students wore a prescribed uniform — a navy blue sailor girl dress with pleated skirt, and a matching beret. Imagine the Sister’s shock when among forty-five girls in her class, forty-four wore sailor hats, while the forty-fifth — Leslie, who else? — came to school in a dashing little red and white checkered bonnet. As a result, she was banned from the ten-minute morning recreational games for a week — to show that neither vanity nor disobedience would be tolerated in the convent.

As could be expected, at first Leslie built up a certain amount of resentment against her new environment. It wasn’t easy to get used to the discipline, the uniformity, the long working hours — every day from eight to twelve in the morning, from two to five in the afternoon, with plenty of homework to keep oneself busy during the evenings.

Yet, what Leslie objected to during her youth, she learned to appreciate when she’d grown up. Her training paid ample dividends. It helped her to get adjusted to the many problems she faced in later years, to get along with people, even further her career.

However, her transition from the sheltered convent life to the exciting existence of a ballet dancer was so abrupt that it didn’t come about without a severe shock — which almost ended her career before it really started, and nearly sent her back to the protective walls of the convent.

Artists, generally, live more carefree lives than any other group of people. But even among artists, ballet dancers stand out as a group all their own, whose easy-goingness is traditional. Due to their work, they are constantly either all the way up, or all the way down emotionally. A bad performance, and half the cast will be in tears. A good critique, and their happiness knows no bounds.

Leslie joined the ballet shortly before they went on a tour of the provinces. Training was hard and intense, and by the time they gave their first performance in Lyons, the ballet master, the choreographer and the members of the ballet would hardly say hello to each other any more. Little misunderstandings turned into major disagreements, and emotional outbursts were as common as tourjetes and pirouettes.

Leslie, absorbed in her new work, her surroundings, the people she met and the places she visited, was first startled and then depressed, by the tensions and supposed conflicts she saw mounting around her. Then came opening night — a glorious success — and, to celebrate, a completely gay and happy party afterward. Gone were all signs of discord.

She soon came to realize that frayed tempers were to be expected in the hardworking days of rehearsals, among people whose careers put them in a world all their own. But, her first experiences with the tensions bound to be a part of the creative development of a ballet, all but sent her running. And had she gone, neither the citizens of France nor American audiences would have heard of Leslie Caron.

It was lucky for Leslie that she was taken under the wing of the ballerina Nathalie Philippart, daughter of the Mayor of Bordeaux. Nathalie became mother, sister, adviser and confidante. Under her watchful eyes, the transition from convent to ballet became more gradual, more cushioned, more acceptable to Leslie.

Today, thinking back on her training in the convent and parochial schools, Leslie can at last appreciate the many benefits of her early upbringing. In little things, in big things, her thinking and actions are influenced by the teachings of the Sisters who didn’t train her to be a good ballet dancer, but who instilled in Leslie the knowledge that the prime function of a woman is to become a good mother and a perfect lady.

Modesty, which annoyed the young Leslie of the Convent de L’Assumption, today puts her in good standing in Hollywood. She has already earned a reputation for being one of the most lady-like young actresses in the movie capital.

Whereas a few years ago she thought it smart to go to school in a flashy little bonnet when the rest of her class wore sailor hats, today she wouldn’t think of being seen outside her house without gloves.

Sometimes this gets her into rather peculiar situations…

A few weeks ago, while completing a painting she’d started at the Palos Verdes Art School, she suddenly craved a chocolate ice cream soda and headed for Schwab’s Drug Store, a few minutes drive from Leslie’s Laurel Canyon home.

Ten minutes later, the soda jerk at Schwab’s — who thought he’d seen everything Hollywood had to offer — did a double take when he saw the petite French actress walk over to the fountain, dressed in an old blouse, pedal pushers, play shoes — and a pair of white gloves!

There are other traits deeply embedded in Leslie’s conscience. The long, intense study hours at the convent make anything her studio demands from the young actress look like child’s play. While many other stars may regard their working schedule as rigid — early hours, constant rehearsals, wardrobe changes and interviews — to Leslie, movie work such as she is currently doing in “Two Girls From Bordeaux,” is like a perpetual vacation which leaves her ample time to go after all her beloved avocations — from painting to bathing her dogs.

In her relationships to studio officials, reporters and the public, Leslie’s natural politeness, a direct result of the curtsies of former days, is a definite asset.

Another advantage of her convent-day schooling is the practical things she’s learned: cooking, sewing, embroidery, keeping house.

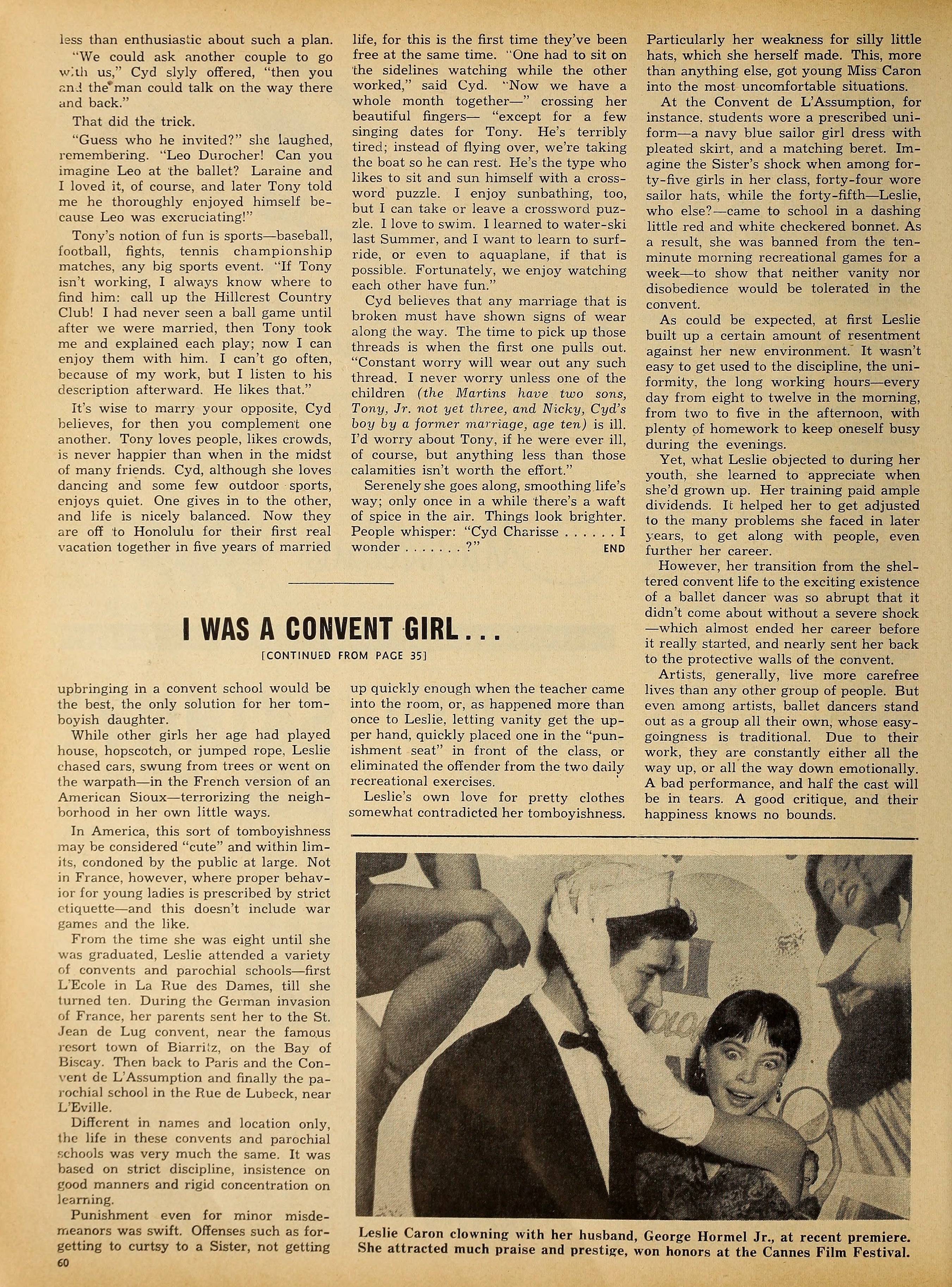

Geordie Hormel, Leslie’s husband, says that she’s never bought a dress which compares with the clothes she herself designed and sewed. Her embroideries have won praise at many Hollywood parties, and her knowledge of materials has already saved the young couple a pretty penny.

What Leslie learned in the convent is today of utmost importance to her, to Geordie, to the family they hope to have. It gave her an aim in life, a pillar to lean on in trying times. It taught her that material things are only temporary, it trained her to concentrate on values which are far longer lasting, and much more gratifying.

Looking back at her early life today, Leslie Caron no longer minds the curtsies, the front seats in classes, the uniforms and strict conformance to rules. She is glad she was a convent girl, for the experience gave her a happy, gratifying attitude toward life.

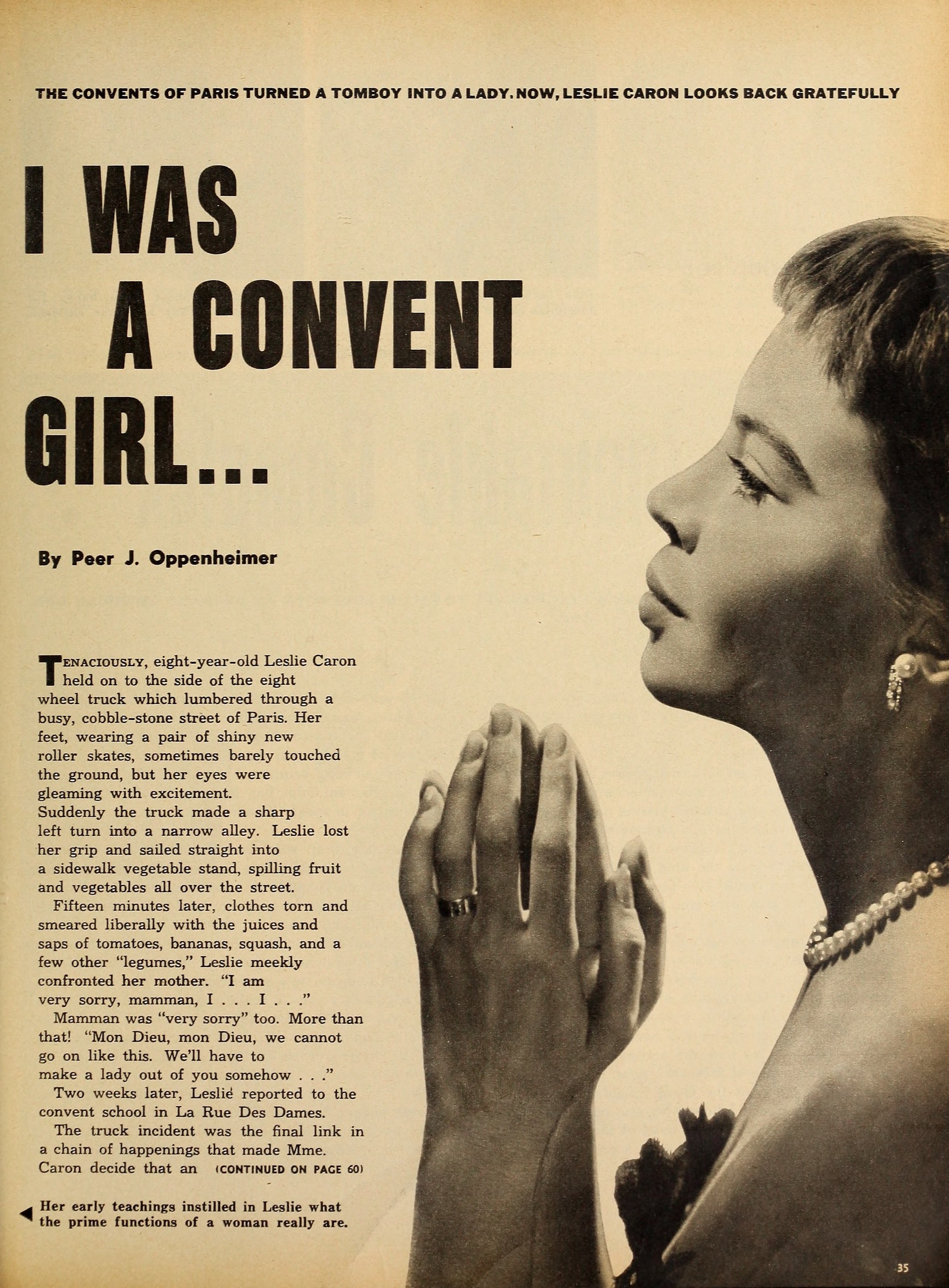

Her early teachings instilled in Leslie what the prime functions of a woman really are.

Leslie Caron clowning with her husband, George Hormel Jr., at recent premiere, She attracted much praise and prestige, won honors at the Cannes Film Festival.

End

Collection: Screenland Magazine, August 1953