The Art of Alla Nazimova (1925) 🇬🇧

Nazimova is back with us again. The speaking stage could not hold her, this creature of fire and ice and rushing thought, from the drama of silent pantomime which she has made so peculiarly her own.

by E. R. Thompson

For the kinema is in her blood — in her face — in her expressive fingertips. She thinks in terms of movement; she speaks most clearly with silence. The kinema has her — and will always have her. And yet in her genius she is free.

Nazimova [Alla Nazimova] has been likened to Pola Negri, to Norma Talmadge, to Theda Bara, and to all the famous emotional stars in their time. But she is like none of them. She is herself, and alone.

Other stars have flashed a brilliant portrait across the screen, have acted with power and colour, have won their places in the hearts of picturegoers the world over, but Nazimova — leaving hearts untouched — has carved for herself a niche with Chaplin [Charles Chaplin] on the lonely pinnacle of screen art.

The appeal of Nazimova is never to the heart, but to the head. We admire her. marvel at her, worship her, perhaps, but love her — never. We cannot love where we do not know, and Nazimova is aloof — a mystery.

The stars who have been loved most warmly have been loved for themselves and not for their shadow on the screen. It was the woman behind the actress in Mary Pickford that became The World’s Sweetheart, the man behind the player in Wallace Reid who caught and held the devotion of packed audiences from Pasadena to Bucharest.

Think of your own favourite, Meighan [Thomas Meighan] or Betty Balfour or Novarro [Ramon Novarro], or whoever it may be. You admire him, yes; you think him versatile, yes; you are glad when his parts give him dramatic scope, yes again; but the thing that holds you is the personality behind the talent, the loved familiarity, the sense of growing comradeship, and the glimpse that breaks through the celluloid now and then of the living and thinking man.

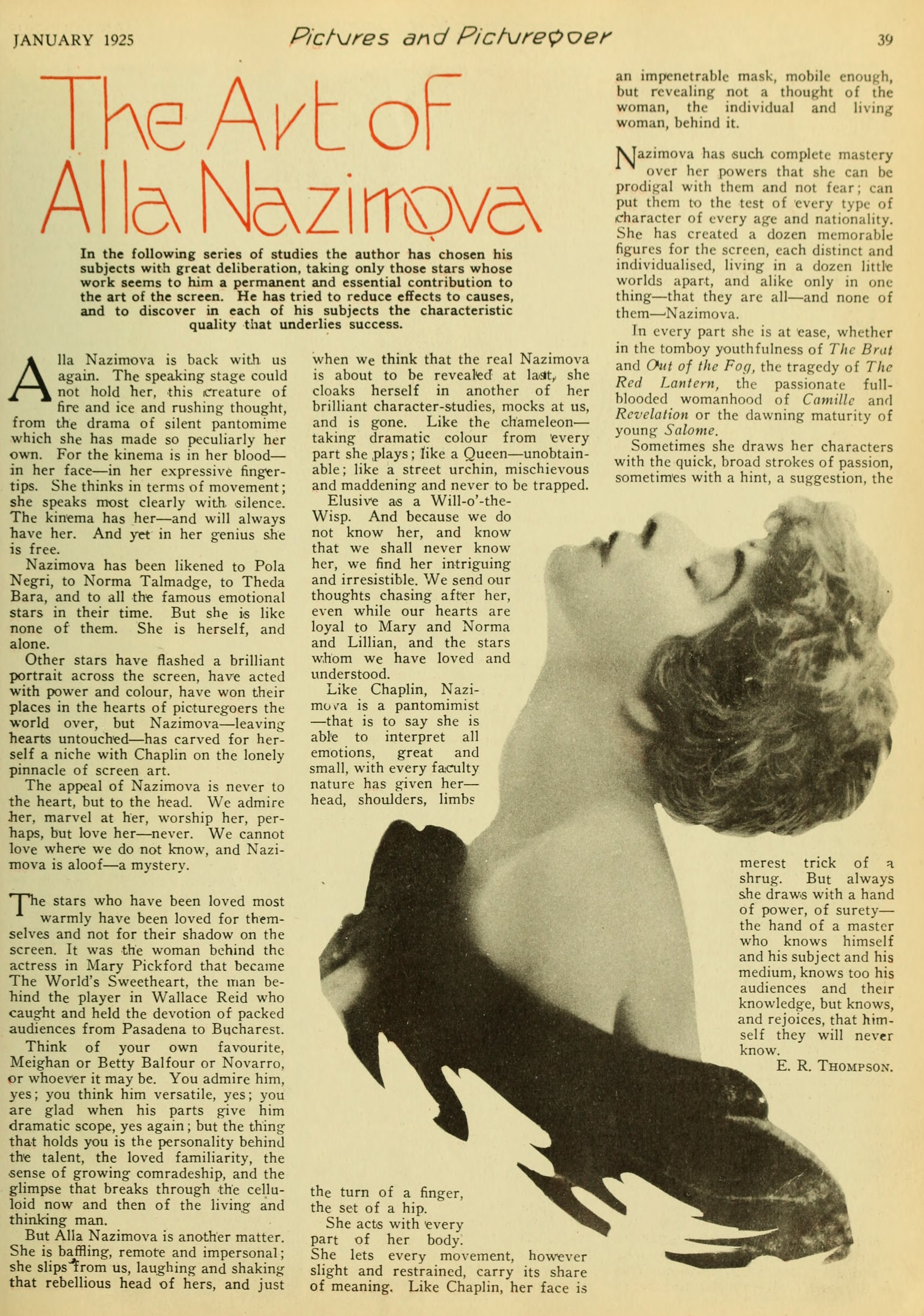

But Alla Nazimova is another matter. She is baffling, remote and impersonal; she slips from us, laughing and shaking that rebellious head of hers, and just when we think that the real Nazimova is about to be revealed at last, she cloaks herself in another of her brilliant character-studies, mocks at us, and is gone. Like the chameleon — taking dramatic colour from every part she plays; like a Queen — unobtainable; like a street urchin, mischievous and maddening and never to be trapped.

Elusive as a Will-o’-the- Wisp. And because we do not know her, and know that we shall never know her, we find her intriguing and irresistible. We send our thoughts chasing after her, even while our hearts are loyal to Mary and Norma and Lillian, and the stars whom we have loved and understood.

Like Chaplin, Nazimova is a pantomimist — that is to say she is able to interpret all emotions, great and small, with every faculty nature has given her — head, shoulders, limb, the turn of a finger, the set of a hip.

She acts with every part of her body. She lets every movement, however slight and restrained, carry its share of meaning. Like Chaplin, her face is an impenetrable mask, mobile enough, but revealing not a thought of the woman, the individual and living woman, behind it.

Nazimova has such complete mastery over her powers that she can be prodigal with them and not fear; can put them to the test of every type of character of every age and nationality. She has created a dozen memorable figures for the screen, each distinct and individualised, living in a dozen little worlds apart, and alike only in one thing — that they are all — and none of them — Nazimova.

In every part she is at ease, whether in the tomboy youthfulness of The Brat and Out of the Fog, the tragedy of The Red Lantern, the passionate full-blooded womanhood of Camille and Revelation or the dawning maturity of young Salomé.

Sometimes she draws her characters with the quick, broad strokes of passion, sometimes with a hint, a suggestion, the merest trick of a shrug. But always she draws with a hand of power, of surety — the hand of a master who knows himself and his subject and his medium, knows too his audiences and their knowledge, but knows, and rejoices, that himself they will never know.

Collection: Picturegoer Magazine, January 1925

---

The Art of… series:

- 1925–01 — Alla Nazimova

- 1925–02 — Adolphe Menjou

- 1925–03 — John Barrymore

- 1925–04 — Charles Chaplin

- 1925–05 — Pola Negri

- 1925–06 — Douglas Fairbanks Sr.

- 1925–07 — Leatrice Joy

- 1925–08 — Bernhard Goetzke

- 1925–09 — Mary Pickford

- 1925–10 — Ernst Lubitsch

- 1925–12 — Ian Keith